Family history doesn’t always lie quietly in parish registers and probate files, sometimes it turns up in formal historical writings and occasionally leaves a mark on the landscape itself. My fourth great-grandfather left an extraordinary trail, featuring map-bending, bear-keeping, and Native American folk medicine.

Hendrikus, better known as Henry, Brevoort was born in New York City in October 1747 and baptised later that month in the Dutch Reformed Church.[i] His family’s roots in the city stretched back to the earliest days of Nieuw Amsterdam when his 2nd great grandfather, Hendrick Janszen van Brevoort, emigrated from Bredevoort, in the province of Gelderland, in the eastern Netherlands.[ii] His name literally translates as “Henry son of John from Brevoort” and followed the patronymic naming system of the time. Hendrick, settled in the Dutch colony at Manhattan and it was said in the family that the bricks of the original Brevoort homestead were brought from Holland – a symbolic anchoring of Old-World origins in New World soil.

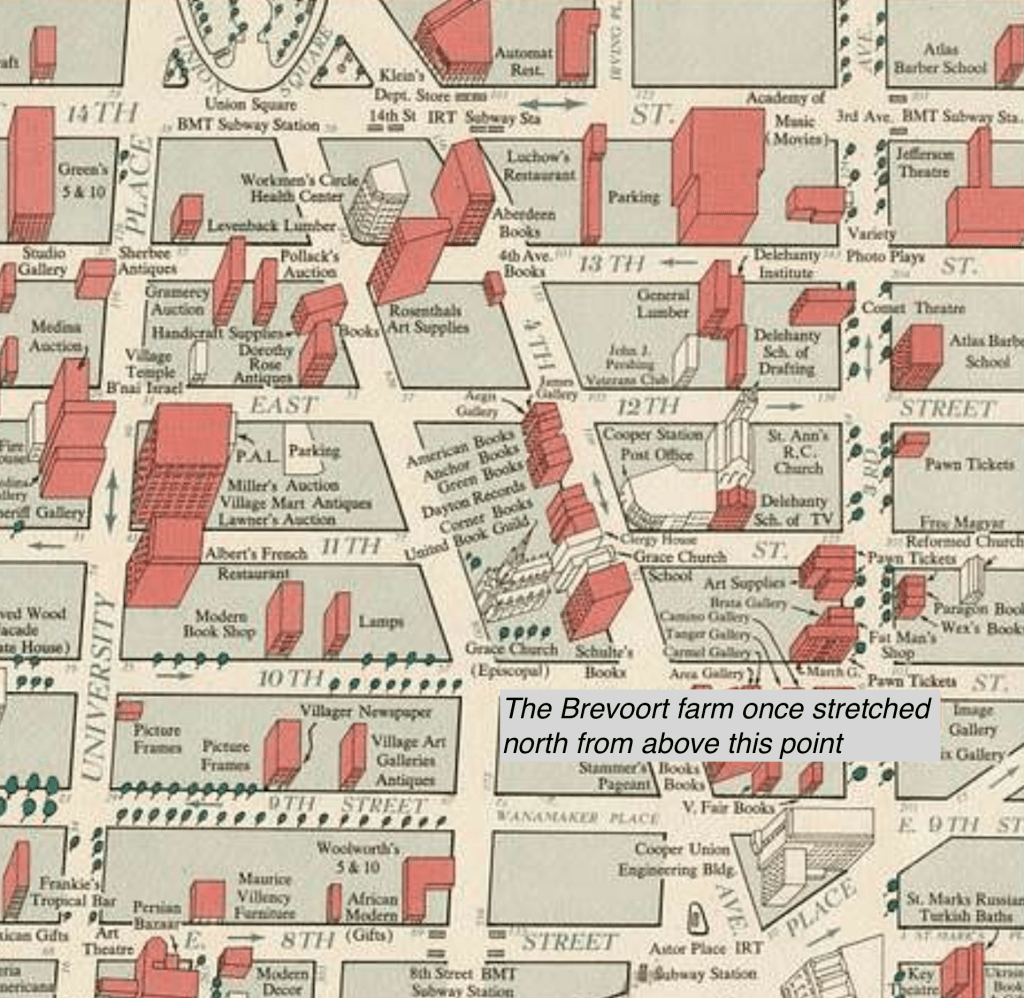

By the mid-eighteenth century the Brevoort farm stretched across a vast swathe of what is now Manhattan, but, as the value of the land increased when New York expanded northwards, it began to be broken up. About twenty-three acres north of Sixteenth Street were sold in 1762, and a further twenty-two acres between Fourteenth and Sixteenth Streets passed out of the family a little later, eventually becoming the Spingler property near present-day Union Square. What remained fell to Henry’s father and was divided into six roughly equal shares.

By the time Henry inherited his portion of the Brevoort estate in 1771[iii], much of the original farm had already passed out of the family, but the Brevoort holding still comprised some eighty acres, bounded roughly by today’s Third and Sixth Avenues and Ninth and Eighteenth Streets. The old stone house stood near its centre, facing what is now Eleventh Street, with a wooden addition and piazza fronting the Bowery. Nearby stood an old Dutch barn, its oak timbers hewn from trees grown on the land itself.

Henry inherited the most southerly portion, which included the old house, and in time he enlarged his holding by purchasing adjoining shares from his brother Charles.

Henry married Sarah Whetten in 1778[iv] during the Revolutionary War, while New York was under British occupation. Sarah came from a patriot family and she, her mother and sister were very active during the conflict and became known as “the damnedest rebels in New York”. A link to their story is included at the foot of this piece.

Between 1782 and 1804, Henry and Sarah had four children, Henry Junior, William, Margaret, and Elias, who grew up on the family farm which extended from The Bowery to between Fifth and Sixth Avenue, up to Eighteenth Street at its northern tip. The house itself stood on the line of Eleventh Street.

Family recollections[v] describe a garden north of Ninth Street and Fifth Avenue, with asparagus beds where traps were set for quail, and a barn that doubled as a wheelwright’s shop – Henry’s trade. He was also fond of collecting animals and birds. At one point, he famously kept a bear chained in his watermelon patch west of Broadway, along with a couple of deer. He also loved to spend time sitting beneath his favourite tulip tree smoking his pipe and watching the world go by. A later verse would describe him spending long hours beneath the tree, smoking quietly and reflecting, treating the tree almost as a companion. It was said to be his “best friend” – one that neither argued nor deceived him, but simply echoed his thoughts in the movement of its leaves.[vi]

Not surprisingly, Henry remained attached to the old house and the tree and those attachments would have consequences far beyond his own lifetime.

In 1807, the New York legislature appointed commissioners – Gouverneur Morris, Simeon DeWitt, and John Rutherford – to plan the city’s future growth. Their 1811 plan imposed the grid of streets and avenues that still defines Manhattan today. Broadway, an older road, was meant to terminate at Twenty-third Street, but pressure soon mounted to extend it northwards in a straight line.

However, though the city made efforts to cut the street through the Brevoort farm, all attempts were blocked, Henry sat tight and refused to budge.[vii]

Had Henry agreed, Broadway would have passed uncomfortably close to his house, and the opening of Eleventh Street would have required its demolition. He refused. At a time when private property rights outweighed the imagined needs of future millions, Henry’s stubbornness prevailed. Broadway was diverted – producing the distinctive dog-leg bend that still interrupts Manhattan’s grid today.

It’s interesting that Henry Brevoort’s reputation extended beyond landownership and stubborn principle. He also grew Indian hemp, a form of cannabis, on his farm and dispensed it freely, if not entirely without expectation.

His son Henry later wrote to his friend Washington Irving,[ix] reporting with some amusement that “the old Gent has lately become much renowned” for curing the Earl of Huntingdon of dropsy using a root of Indian hemp. According to the letter, the Earl was close to death, and the cure, which came about “by the merest accident”, proved so effective that it was credited with saving not only the Earl, but also old Henry Brevoort himself, and a child of the Renwick family suffering from dropsy of the head.

It’s not clear how the cure was administered, but this was not an isolated episode. A later anecdote, published in 1909, recounts how Indian hemp was sought for John Watts de Peyster who suffered from a heart condition. The only known source was “old Mr. Henry Brevoort,” and a messenger was dispatched with money and instructions to use diplomacy if necessary.

The messenger found Brevoort in his familiar red flannel shirt, napping outside his low-storied cottage on the Bowery. He gently woke him and explained his mission. The old man raised no objection, dug up the hemp himself and handed it over, flatly refusing payment. “I never sells it,” he explained, “because if I takes money for Indian hemp, it weakens the vartoo.” [author’s note: I think ‘vartoo’ = virtue]

Thus, his visitor prepared to leave – only to feel a firm hand restrain him at the gig step. “I never sells Indian hemp,” Brevoort whispered, “but if I gives it, I never refuses a present.”

The money was duly handed over, and the story, like so many connected with Henry Brevoort, was laughed over for years afterwards.[x]

Henry Brevoort lived to the age of ninety-three – his longevity possibly enhanced by the beneficial effects of the Indian hemp. He died on Sunday 22 August 1841 at his home on the Bowery, New York[xi].

By then, the countryside of his youth had vanished beneath streets and churches. The old homestead is now long gone, its site today occupied by Grace Episcopal Church, designed by Henry’s grandson James Renwick Jnr[xii], but traces of old Henry’s world endure – in family memory, in old maps, and in the stubborn bend of Broadway itself.

You can read the story of Henry’s wife Sarah, her mother Margaret, and her sister – known to the British as “the damnedest rebels in New York” here.

[i] The Holland Society of New York, New York Records, Volume I, Book 33 via http://www.ancestry.co.uk

[ii] New York “Knickerbocker” Families: Origin and Settlement published 1914 by New York Genealogical and Biographical Society via https://www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org last accessed 8 Feb 2026

[iii] The Todd Genealogy by Richard Henry Green published 1867 by Wilbur & Hastings via www.googlebooks.com last accessed 8 Feb 2026

[iv] The Todd Genealogy by Richard Henry Green published 1867 by Wilbur & Hastings via www.googlebooks.com last accessed 8 Feb 2026

Genealogical and family history of southern New York and the Hudson River Valley; a record of the achievements of her people in the making of a commonwealth and the building of a nation; (Cuyler, 1866- comp Reynolds)

[v] Letters of Henry Brevoort Jnr to Washington Irving published 1916 by GP Putnam’s Sons from the author’s personal collection

[vi] Ballads of Old New York by Arthur Guiterman published c1920 by Harper & Brothers via www.archive.org.ukl last accessed 8 Feb 2026

[vii] The greatest street in the world : the story of Broadway, old and new, from the Bowling Green to Albany by Stephen Jenkins published 1911 by GP Putnam’s Sons via www.archive.org.uk last accessed 8 Feb 2026

[viii] Public domain scan, free to use, no copyright restrictions – via www. https://picryl.com last accesse 8 Feb 2026

[ix] Letters of Henry Brevoort Jnr to Washington Irving published 1916 by GP Putnam’s Sons from the author’s personal collection

[x] John Watts de Peyster by Frank Allaben published c1908 by Frank Allaben Genealogical Company via www.archive.org last accessed 8 Feb 2026

[xi] New York Evening Post: Deaths 1839-1840 via www. ancestry.co.uk

[xii] Wikipedia www.wikipedia.com last accessed 8 Feb 2026

[xiii] Ballads of Old New York by Arthur Guiterman published c1920 by Harper & Brothers via www.archive.org.ukl last accessed 8 Feb 2026