This story draws on nineteenth-century parish, census, and civil registration records. It includes historical terms and causes of death relating to infant mortality and disability that may feel stark or distressing today. Such language reflects the medical understanding and record-keeping practices of the time and is included for accuracy and context.

Charlotte Mayhew was born in Rendlesham, Suffolk, around 1816,[i] into a rural working family. Her father Michael Mayhew, supported the household first as a gamekeeper and later as a carrier, transporting goods and people by horse and cart between nearby villages; Her mother Elizabeth (née Barrett) would bear at least a dozen children, and Charlotte was probably the ninth, raised in a household where illness, hard work, and loss would not have been unfamiliar.

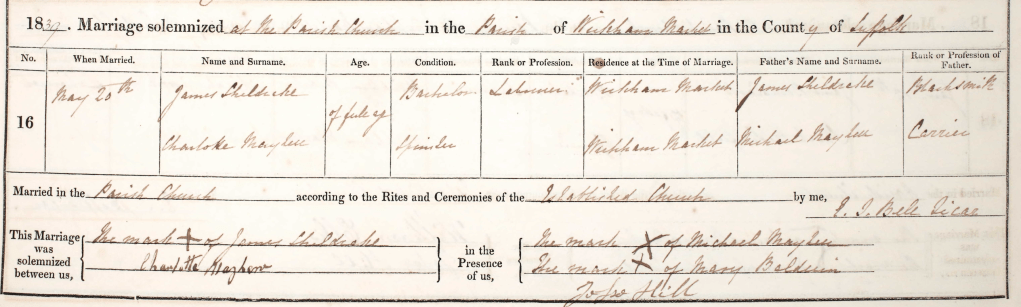

By the spring of 1839 Charlotte and her family were living in Wickham Market where, on 20 May, she married James Sheldrake at the parish church.[ii] James was a labourer, son of a blacksmith, and Charlotte had no occupation recorded. James made his mark in the register, as did two of the witnesses, one of whom was Charlotte’s father Michael. The third witness was Jesse Hill, the parish clerk, who completed the register. Charlotte signed her name. Unlike many women of her background, she had learned to read and write – a small but telling marker of competence and self-possession that follows her through the records.

What the register does not show was that Charlotte was already heavily pregnant. Four days after the wedding, their son James was baptised in the same church, but the following day he died. In the civil register he appears as William Sheldrake,[iv] aged three days, with the cause given simply as “inflammation” – a term often used in the nineteenth century for a wide range of acute conditions, including infection, respiratory distress, or complications of birth. Infant mortality was high, particularly in the first few days of life, when medical intervention was minimal and childbirth itself carried grave risks to both mother and child.

The informant was not one of the baby’s parents, but Martha Lanham, an elderly woman who acted as a lay midwife and nurse within the local community who had been present at the death. Martha could neither read nor write and endorsed the register with her mark. This may help explain the anomaly of the child’s name being recorded as “William”, perhaps through misunderstanding or error when the death was reported. Whether Charlotte was too ill, too shocked, or simply absent from the formalities is not known. Only seven days after their marriage, Charlotte and James buried their son in Wickham Market churchyard.[v]

A year later, Charlotte gave birth again but her daughter, also named Charlotte, lived for just six weeks.[vi] The cause of death was reported by Martha Lanham as “mortification”, a term commonly used to describe tissue death caused by infection or sepsis. In an age before antibiotics or effective antiseptics, even minor infections could rapidly become fatal, particularly in infants. Little Charlotte was buried in Wickham Market churchyard on 3 August 1840.[vii]

The 1841 census shows Charlotte and James, now described as a blacksmith like his father, living on Upper Street, Wickham Market,[viii] in the same household as Charlotte’s parents, Michael and Elizabeth Mayhew, and her younger brother William. The shared entry, separated only by a single dash, places them within one extended family household, a practical arrangement that likely reflected both economic necessity and mutual support. The record, however, remains silent about the losses already endured.

Later that year, Charlotte gave birth again. The baby, a boy named James, was baptised privately on 11 July 1841[ix] – an act that speaks of urgency and fear. Private baptisms were usually performed when a child was not expected to survive, suggesting that the family, or midwife, recognised the danger. James died the following day, aged just four days, and the cause given by Martha Lanham – now explicitly described as a “nurse” – was “fever”,[x] a broad diagnostic term that might encompass neonatal infection, convulsions, or complications arising during labour. His tiny body was buried in Wickham Market churchyard on 17 July.[xi]

By the spring of 1843 Charlotte was pregnant again, and in April she gave birth to a fourth child, another daughter named Charlotte. It was not uncommon then for younger children to be named after deceased siblings. This Charlotte lived for just two months. Her death certificate records “consumption”, [xii] often assumed to mean tuberculosis, although in infants this term was sometime applied more loosely to wasting illnesses marked by persistent weakness and decline – what would now be described as failure to thrive. For the first time Charlotte herself, present at the death, registered the loss of one of her children. Baby Charlotte was buried in Wickham Market on 8 May 1843.[xiii]

The repetition of these losses – four children buried in just four years – would have been physically and emotionally devastating, even in a society accustomed to infant death.

Charlotte’s family continued to be touched by tragedy. The following summer her mother Elizabeth died of rheumatism.[xiv] Charlotte, present at the death, stepped forward to register this event, and her mother was buried in Wickham Market churchyard on 23 June 1844.[xv]

Then, in January 1845, Charlotte’s husband James – a normally fit and strong young blacksmith – died aged just twenty-nine. The cause of death was recorded as epistaxis, commonly known as a nosebleed. Not normally fatal, a severe or uncontrollable bleeding from the nose could indicate sudden illness or an underlying condition poorly understood at the time, and there is no indication that he was seen by a doctor. Charlotte, present at his death, once again stood as informant.[xvi] James was buried in Wickham Market churchyard on 5 February 1845.[xvii]

Charlotte was not yet thirty. She had lost all four of her children, her mother and her husband within six years.

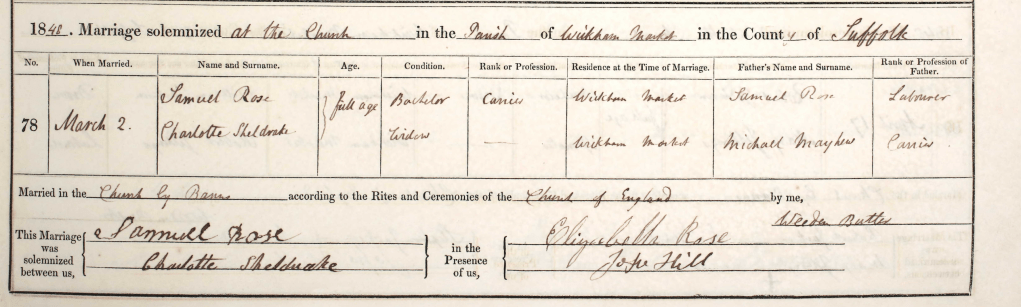

Three years later, on 2 March 1848, Charlotte married again.[xviii] Her second husband, Samuel Rose, was a carrier who may have worked alongside her father. This time both bride and groom signed the register. Witnesses Elizabeth Rose – who may have been related to the groom, though she has not yet been identified – and Jesse Hill, Wickham Market’s parish clerk, who had also recorded Charlotte’s first marriage. Together, they suggest a quiet wedding, with few present at the ceremony.

Just a few weeks later, their son Samuel James Rose was born and baptised at Wickham Market parish church on 29 April 1848,[xx] in the same font as his half-siblings. He lived for just fourteen weeks. His cause of death as certified, “anaemia from birth”, indicates that he had been seen by a doctor and suggests a congenital condition, chronic weakness, or failure to thrive – diagnoses that nineteenth-century medicine could recognise but rarely treat. His father Samuel registered the death and, on 31 July 1848, another child was buried in Wickham Market churchyard.[xxi]

For Charlotte, five children, and five graves.

Two years later Samuel Rose, appeared before a magistrate at Ipswich, having been arrested by the rural police for “want of sureties to keep the peace.” The prosecutor was Charlotte herself. Samuel was sentenced to three months in Ipswich gaol. The prison receiving book, although rich in detail about Samuel’s physical description and possessions, is restrained in its account of the offence. Nevertheless, the conviction suggests domestic conflict serious enough to reach the courts. A note in the record states that Charlotte was “being supported by her friends”, hinting at both hardship and the quiet local safety net of kinship and community.[xxii]

By 1851 Charlotte and Samuel were living together in the home of her elderly father, Michael Mayhew, on Bridge Street, Wickham Market, where both men are listed as common carriers.[xxiii]

Charlotte gave birth to another son on 11 January 1852. Michael Mayhew Rose, named unmistakeably for her father, was baptised on 11 July that year, with both Samuel and Charlotte named as parents.[xxiv] After this point, Samuel disappears from the records. Whether he died, deserted his family, or simply slipped beyond trace remains unknown. What is clear is that Charlotte increasingly turned back towards her own family.

Michael senior died in March 1855 aged eighty-seven, having suffered from senile gangrene for six weeks. His death was certified, indicating he had been seen by a doctor, and was likely nursed by Charlotte who was present at the death.[xxv] Charlotte registered her father’s death herself, and he was buried in Wickham Market churchyard on 28 March.[xxvi]

Meanwhile, Michael Mayhew Rose survived infancy – the only one of Charlotte’s children to do so – but he was disabled from birth. Later census returns record his condition in the blunt language of the time: “fits from birth” [xxvii] and “idiot from birth”.[xxviii] Such terms reflected contemporary medical and social understanding rather than precise diagnosis. Epilepsy, developmental delay, and brain injury were poorly understood, and there was little in the way of institutional support for families unless they surrendered a child to an asylum or workhouse.

Charlotte did not do this.

Instead, she raised Michael at home for over thirty years. This would have shaped every aspect of her life: limiting her capacity for regular work, increasing dependence on kin, and exposing her to poverty in old age. The care of a disabled child fell almost entirely to mothers, and there was no expectation of state support beyond the parish, often accompanied by stigma.

Charlotte’s later years were spent in diminishing circumstances, she worked as a charwoman when she could, and shared households with relatives and lodgers.

Michael died in 1884, aged thirty, of phthisis – tuberculosis – and diarrhoea.[xxix] Charlotte registered his death herself, as she had so many before. He was buried in Wickham Market churchyard on 20 September.[xxx]

By 1891, Charlotte was on parish relief in May’s Lane.[xxxi] She died in 1899 and was laid to rest in Wickham Market churchyard on 4 September, alongside so many of her family. None of their graves is marked today; they were almost certainly all buried in paupers’ graves.

Her death was reported in the local press as:

“Mrs Charlotte Rose, aged 85 years, who was one of the oldest inhabitants, and had resided here all her life. The deceased was the daughter of the late Michael Mayhew, who in his day was a carrier to Woodbridge. A very active woman at one time, but the last few months had been confined to her bed”.

It saddens me that Charlotte was remembered chiefly as someone’s daughter, rather than as a woman shaped by repeated bereavement, by care work that went unrecorded, and by resilience exercised in private. Her story deserves to be told – to remind us of the lives lived by women who endured, adapted, and carried on, often without recognition, and rarely without cost.

[i] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC173/D/1/5

[ii] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D/2/3

[iii] Ibid

[iv] GRO digital copy of the death of William Sheldrake registered Q2 1839 Plomesgate Vol 12 p287

[v] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D5/1

[vi] GRO digital copy of the death of Charlotte Sheldrake registered Q2 1839 Plomesgate Vol 12 p287

[vii] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D5/1

[viii] 1841 England census, Class: HO107; Piece 1041; Book: 16; Civil Parish: Market Wickham; County: Suffolk; Enumeration District: 3; Folio: 39; Page: 12; Line: 18; GSU roll: 474645 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[ix] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D4/1

[x] GRO digital copy of the death of James Sheldrake registered Q3 1841 Plomesgate Vol 12 p235

[xi] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D5/1

[xii] GRO digital copy of the death of Charlotte Sheldrake registered Q2 1843 Plomesgate Vol 12 p249

[xiii] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D5/1

[xiv] GRO digital copy of the death of Elizabeth Mayhew registered Q2 1844 Plomesgate Union Vol 12 p2

[xv] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D5/1

[xvi] GRO digital copy of the death of James Sheldrake registered Q1 1845 Plomesgate Vol 12 p305

[xvii] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D5/1

[xviii] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D/2/3

[xix] Ibid

[xx] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D4/1

[xxi] GRO digital copy of the death of Samuel James Rose registered Q3 1848 Plomesgate Vol 12 p265

[xxii] Suffolk Archives; Ipswich, Suffolk, England; Suffolk Gaol Records; Reference: A609/9

[xxiii] 1851 England census Class: HO107; Piece: 1802; Folio: 238; Page: 15; GSU roll: 207452 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xxiv] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D4/1

[xxv] Michael Mayhew death certificate (certified copy) in the author’s own files.

[xxvi] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D5/1

[xxvii] 1861 England census Class: RG10; Piece: 1763; Folio: 87; Page: 11; GSU roll: 830789 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xxviii] 1871 England census Class: RG11; Piece: 1887; Folio: 106; Page: 9; GSU roll: 1341455 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xxix] GRO digital copy of the death of Michael Mayhew Rose Q4 1854 Plomesgate Vol 4a p503

[xxx] Suffolk Archives; Suffolk, England; Church of England Parish Registers; Reference: FC103/D5/1

[xxxi] 1891 England census Class: RG12; Piece:1480; Folio:” 189; Page: 3; GUS roll: 6096590

[xxxii] © Copyright Sandy Gerrard and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence via https://www.geograph.org.uk last accessed 16 Jan 2026