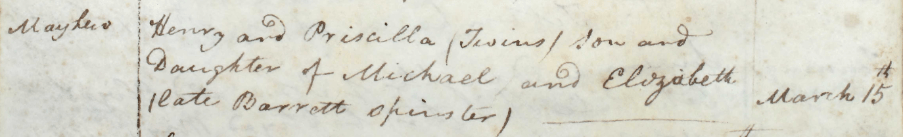

Henry and Priscilla Mayhew were born in the village of Rendlesham, near Woodbridge in Suffolk, and were baptised together on 15 March 1812 at the church of St Gregory the Great. They were the children of Michael and Elizabeth Mayhew (née Barrett), and joined an already large family with six children aged between about twelve and three, and at least three more born during the following nine years.

The twins entered a rural world on the cusp of profound change. Suffolk, at the turn of the nineteenth century, was marked by widespread poverty and growing unrest. Food shortages and political agitation had already sparked riots in the late eighteenth century, and 1812 proved one of the worst years on record for weather.[ii] Spring and summer were bitterly cold and unusually wet, harvests were poor, and the winter that followed remains among the coldest ever recorded. A succession of failed or delayed harvests drove up the price of bread, while wages for agricultural labourers were cut, pushing many rural families to the brink of survival.

By 1815 Britain itself seemed close to breaking point. The long war against Napoleon ended with victory at Waterloo, but peace brought its own hardships: thousands of returning soldiers, suddenly surplus to requirements, competed for scarce work. That same year, the government introduced the Corn Laws, designed to protect British landowners by keeping grain prices high through restrictions on imported corn. For labourers, especially in counties like Suffolk, the effect was disastrous, locking in high food prices while incomes stagnated or fell.

Nature compounded these pressures. In 1815 the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia disrupted global weather patterns, and 1816 became infamous as the ‘year without a summer’.[iii] Cold, rain, and crop failures spread across the northern hemisphere, bringing famine, livestock losses, and renewed misery to rural communities already weakened by years of hardship.

Seasonal work grew ever more precarious. Winter employment traditionally relied on threshing – the laborious beating of grain from its stalks – but from the 1820s onwards new threshing machines began to replace manual labour. These innovations threatened one of the few reliable sources of winter income for farm workers and deepened resentment at a time when desperation was already widespread.

The Mayhew family would have witnessed the consequences of this unrest at close quarters. By the 1830s, anger boiled over into the disturbances known as the Swing Riots. Protesters – signing their threatening letters with the fictitious name ‘Captain Swing’ – broke machines, set fire to hayricks and barns, and targeted symbols of rural authority. In Suffolk, night skies were lit by burning farm buildings, while the government responded with brutal severity: imprisonment, transportation, and executions.

It was amid this prolonged uncertainty and upheaval that the Mayhew family moved a few miles west to Wickham Market. There, Henry and Priscilla’s father, Michael, established himself as a local carrier, transporting goods and passengers between Woodbridge and Wickham Market. It was a modest but vital trade in a countryside still dependent on horse and cart – and a calculated attempt to escape the narrowing prospects of agricultural labour.

From there, Henry and Priscilla’s paths diverged sharply.

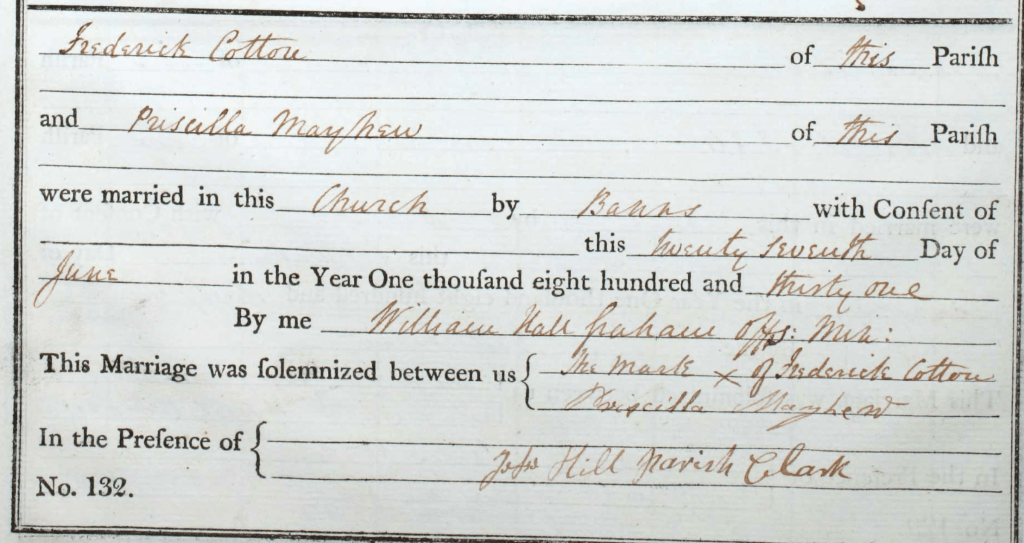

On 27 June 1831, Priscilla married Frederick Cotton, a young gardener, at All Saints Church, Wickham Market.[iv] Notably, Priscilla was able to write her own name in the marriage register, suggesting – unusually for the time – that she had received some education and was able to read and write. Frederick, by contrast, made his mark.

Just three months later, their first son, John, was born on 30 September and baptised in the Church of England on 13 May 1832. Their first daughter, Sarah Ann, followed on 13 October 1833 and was baptised in the Independent Church at Wickham Market on 10 November that same year.[vi] This shift marks the first clear indication that Frederick and Priscilla were moving away from the established religious conventions of their neighbourhood and families.

Within a few years, the couple had fully embraced Baptist beliefs and joined the growing wave of emigration to North America. Their second son, Allen, was born at sea in 1838,[vii] midway through their voyage across the Atlantic. The family settled in Waterford, Norfolk County, Ontario – a well-established Canadian farming region known for its fertile land and thriving network of Baptist congregations. There, the Cottons prospered, raising a large family and becoming part of a close-knit settler community.

Henry, by contrast, remained in England. Around 1840, he joined the mass movement of rural labourers heading to the capital in search of work. He settled in Chelsea, where he married Ann Baker, a servant, in 1843[ix]. The couple had three sons: William James (1844), John Thomas (1846), and Richard Alfred (1849), all baptised into the Church of England at Holy Trinity Church, Upper Chelsea.[x] Henry worked as a labourer during the great building boom that reshaped mid-nineteenth century London. It was hard and uncertain work, and although the family stayed rooted in Chelsea, they never rose out of poverty.

Although Chelsea is now associated with wealth and prestige, in the mid-nineteenth century it was a very different place. Rapid growth had outpaced housing and sanitation, and much of the district consisted of overcrowded courts and poorly drained streets, particularly near the river. Many families lived in single rooms, with insecure tenancies and little protection against illness or loss of work. Employment for labourers was largely casual and seasonal, tied to the building trade and offering no safety net in times of sickness or old age. For families like the Mayhews, poverty was not the result of idleness, but of long years spent on the margins of an expanding city.

Ann died in 1871, aged just fifty-nine, of “bronchitis and general debility”[xii] – an indication of the chronic strain on her health, shaped by years of hardship.

Henry was admitted to the Britten Street Workhouse, Chelsea, on Wednesday 24 March 1880.[xiii] His record classifies him as Class 2: “Able bodied men, and youths above 15”. His occupation was recorded simply as “labourer,” his religion as Church of England, and the reason for seeking relief as “destitute.” He was later transferred to the workhouse infirmary, where he died on 21 January 1881, aged sixty-nine, of a phagedenic ulcer – a deep, necrotic and gangrenous skin infection – and exhaustion:[xiv] an ignominious end to a life of physical toil.

Meanwhile, Priscilla’s life in Canada followed a very different course. She and Frederick raised at least eight children, including twins Martha Jane and Mary Jane born in 1843, and youngest daughter Charlotte Ann in 1855. The Cotton farm was successful, and the family became deeply integrated into the social and religious life of their township. Priscilla died in 1886 aged seventy-four, of congestion of the brain;[xv] Frederick followed in 1891 aged eighty-two, dying simply of “old age”[xvi] – a peaceful end in direct contrast to Henry’s.

The lives of Henry and Priscilla illustrate the stark inequalities of their age. Born just minutes apart on the same day in the same family, they followed very different paths:

Henry remained rooted in the Church of England and the traditional ways of his community, taking what work he could find as a labourer and relying on the patchwork support of parish relief. Priscilla, by contrast, was literate and embraced the opportunities offered by a new faith and a new land, seizing the chance to emigrate and establish a prosperous household in Canada. Henry endured the relentless insecurity of a rapidly expanding city, ending his days in the dreaded workhouse; Priscilla found opportunity, stability, and community across the Atlantic.

Another Henry Mayhew – no relation to the twins, but born in the same year, 1812 – would later chronicle the lives of London’s working poor in his great survey London Labour and the London Poor.[xvii] Walking the streets and interviewing labourers, he observed that “the amount of misery in the metropolis was positively appalling,” and noted that many lived “from hand to mouth, dependent on chance employment, and always on the brink of want.” Such men, he wrote, were poor “not because they will not work, but because they cannot always get work” – a description that fits closely the life Henry of Chelsea endured, though he never wrote a word of it himself.

Together, these three lives show how chance, choice, and circumstance could shape destinies in radically different ways.

Author’s note: Henry and Ann Mayhew of Chelsea were my third great-grandparents, and their youngest son, Richard Alfred Mayhew, my second great-grandfather.

[i] Rendlesham Parish Records 1807-1812, via www.ancestry.co.uk

[ii] https://www.pascalbonenfant.com/18c/geography/weather.html last accessed Jan 2026

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Wickham Market, Register of marriages, 1813-1837, via www.ancestry.co.uk

[v] Ibid

[vi] Wickham Market (Independent), England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567-1936 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[vii] Ontario, Canada Deaths, 1869-1934 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[viii] via www.ebay.co.uk

[ix] St Luke, Chelsea, Sydney Street Marriages and Banns 1837-1850 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[x] Holy Trinity, Chelsea: Sloane Street, Kensington and Chelsea, Kensington and Chelsea, England, births and baptisms 1813-1906 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xi] Wikipedia, image in the public domain, last accessed Jan 2026

[xii] Ann Mayhew death certificate (certified copy) in the author’s personal files

[xiii] London, England, Workhouse Admission and Discharge Records, 1659-1930, Reference Number: CHBG/188/006 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xiv] Henry Mayhew death certificate (certified copy) in the author’s personal files

[xv] Ontario, Canada Deaths, 1869-1934 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xvi] Ontario, Canada Deaths, 1869-1934 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xvii] Labour and the London Poor (1851) by Henry Mayhew