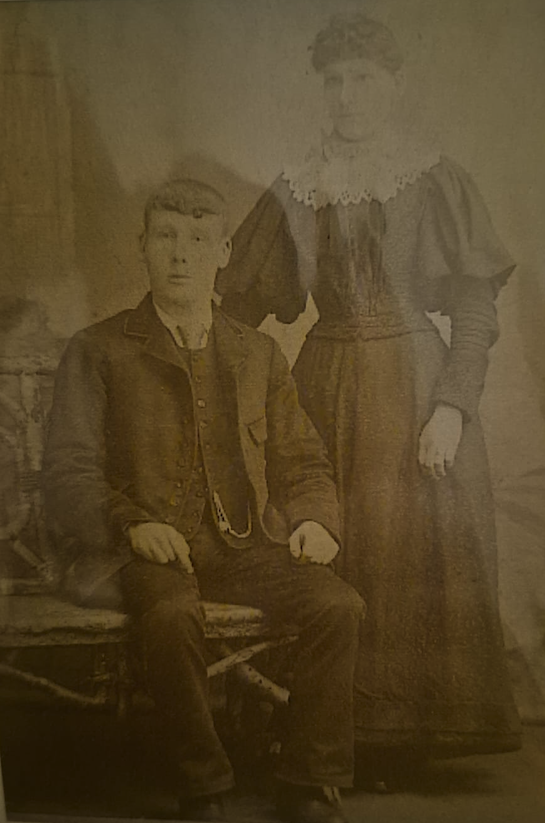

My great grandmother Emma Levens, married my great grandfather Alfred George Mayhew, known as George, in 1892 when they were both nineteen years old.

The couple had seven children of whom two died young. In those days, such tragedies were heartbreakingly common: in 1905, roughly one in five children in the UK did not reach their fifth birthday, [ii] with mortality rates even higher among working-class families in inner-city districts. Then, in 1908, Emma herself died at just thirty-three after complications during the birth of their eighth child.[iii]

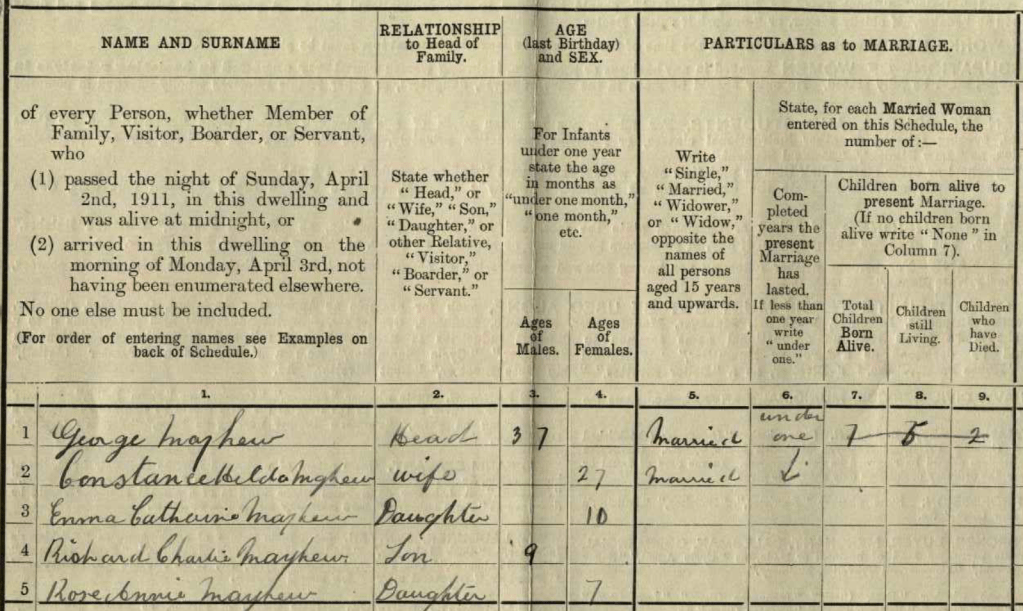

In the early years of my tracing family history, I had researched six of their children, but there was no trace of the seventh. I was confident there were in fact seven, because the 1911 census – the first to be filled out by the householder – shows George living with his new wife, Constance, and three of Emma’s children: Emma Catherine (10), Richard Charlie (my grandad, aged 9), and Rose Annie (7). Fortunately for later family historians, George noted that seven children had been born alive, five were still living, and two had died. However, as George and Constance had only been married a few months, the enumerator added a note to that effect and struck through the numbers for children, as they related to George’s previous marriage.[iv] From this single detail, I knew there was a missing child still alive somewhere in 1911 and I assumed that this was the baby born around the time of Emma’s death three years previously.

But despite years of searching, this seventh child remained invisible – no birth, no baptism, no census entry, no death certificate. I had already established, from censuses, school records, and institutional admissions, that four of the children had moved around in the immediate aftermath of their mother’s death. It made me wonder whether the baby had been quietly passed to a friend or relative to be cared for, slipping out of sight just long enough to disappear from the formal record altogether.

The big breakthrough came during a video call with a cousin I had not spoken to for fifty or sixty years. It was wonderful to catch up after so long and, almost casually, he mentioned that he had a handwritten “family tree” recording our grandfather’s parents and siblings. A short while later, an image of the document arrived via WhatApp.

It had been carefully handwritten in pencil, and the transcription reads:

Given to Emma by her father in Remembrance of her Dear Mother who died on January 13th 1885 aged 45. Entered [sic] at Norwood Cemetery.

Emma Levens married to George Mayhew on 20th Nov 1892. Ages 19 x 19.

Emma Mayhew aged 31 — 29th July 1904 — Born 1873

George Mayhew aged 31 — 24th May 1904 — Born 1873

- Edward George — Born 29th day of February 1893; died 23rd April 1895, aged 3 years 2 months. Entered at Fulham Cemetery, grave no. 31K.

- William John Mayhew — Born 7th June 1894.

- George Mayhew — Born 2nd day of Sept 1896; died 16th August 1897, aged 11 months. Entered at Fulham, grave no. 21F.

- Emma Catherine Mayhew — Born 27th June 1901.

- Richard Charles Mayhew — Born 27th October 1902.

- Rose Annie Mayhew — Born 26th May 1903.

- Violet Mayhew — Born 6th March 1907.

Emma Mayhew — Died 9th April 1908, aged 33 years. Entered at Fulham Cemetery, grave no. N9.

William John Mayhew — Aged 12 years — Sent to an Industrial School in York on 26th June 1906.

There it was at last: the missing child wasn’t the baby born in April 1908, but a daughter born thirteen months earlier – a little girl named Violet.

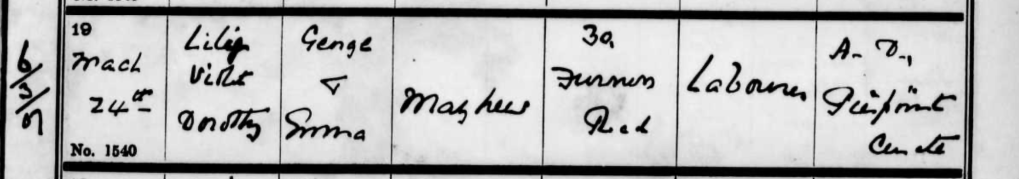

I searched through the records and, now armed with the correct year and a name, quickly found a baptism dated 24th March 1907 at St Matthew’s Church, Fulham. The note in the margin gives her date of birth. Her parents are recorded as George and Emma Mayhew of 30 Furness Road, and her father’s occupation is listed as labourer.

I was elated – every detail matched what I had already figured out. But there was one surprise: on the baptism record, her full name was the rather delightful Lily Violet Dorothy.

There is a tradition among my male Mayhew forebears to give a boy two official names and then call him by the second one. Given that background – and the ambiguity in the records – I’ve decided to continue using Violet as her given name, as it appears on the handwritten family tree.

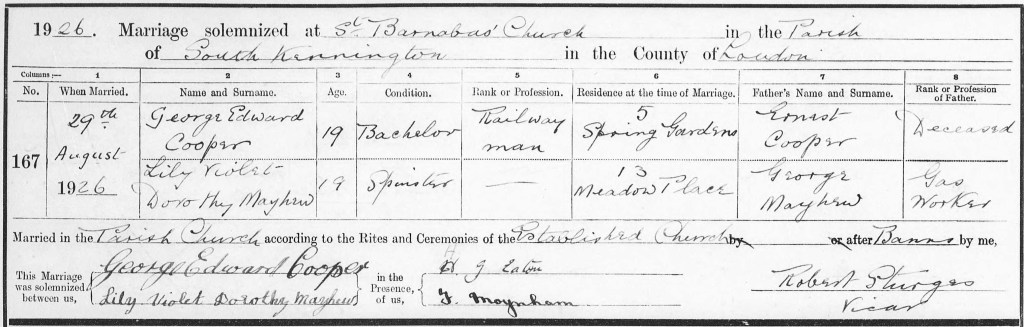

With this new evidence of her name and date of birth, I began searching the records again and quickly found a promising lead: a parish record of the marriage of Lily Violet Dorothy Mayhew, aged 19, to George Edward Cooper, also 19, at St Barnabas Church, Kennington, on 29 August 1926. The bride’s address was listed as 13 Meadow Place, and her father as George Mayhew, a gas worker. Everything fell neatly into place – and I couldn’t help noticing that Violet and George were exactly the same age as her parents had been when they married thirty-four years earlier.

My next lead was the 1921 census, where I hoped Violet might reappear under a different household or surname. When I searched for the occupants of 13 Meadow Place, I found a pair who immediately caught my attention: Annie Peppler, a widow of nearly sixty-seven, and Violet Peppler, aged fourteen. Annie had written that Violet was a “shop assattince” (the enumerator diplomatically corrected this to “assistant”) – working at Spencer Bazaar on Station Road, Brixton. Her entry also carried a note: father dead, mother alive.

Something about this pair felt slightly off kilter. Annie seemed too old to be the mother of a fourteen-year-old girl, yet here was a “Violet,” with the right age, living in Brixton and with one parent deceased. The combination was too compelling to ignore. If this wasn’t my Violet Mayhew, she was an astonishing coincidence.

To understand who Annie was – and whether she might have been caring for Violet – I stepped back a decade to the 1911 census, the first to be filled out by the householder rather than the enumerator. These early self-reported records, along with the 1921 census, often contain spelling mistakes, errors, and miscalculations, so details always need careful checking. There I found a couple living at 4 Layham Cottages, South Lambeth: Alfred Pepler, a forty-eight-year-old Post Office labourer storekeeper, and his wife Anne, aged fifty-one. They had been married for only five years and in their household was a three-year-old “adopted” daughter: Lilly Mayew, born in Fulham.

The moment I saw that entry, everything came into focus. A toddler known as Lilly Mayew, the right age, the right birthplace – and in the care of an Anne (or Annie) Pepler/Peppler. It was as if Violet’s trail, invisible for so long, suddenly flickered back into view.

I tracked Annie back through her marriages and discovered that she was none other than Violet’s mother’s older sister, Ann Levens. Her story is fascinating in its own right, but that is perhaps a tale for another day.

So, Violet/Lily was taken in by her aunt Annie, probably within days of her mother’s death. Annie would not have formally adopted her, as adoption had no legal basis in the UK until 1926. It’s likely that Violet was unofficial fostered by her aunt. Fostering – where a child lives temporarily with another family – began to be regulated from the mid-19th century following a series of “baby farming” scandals. By the end of the century, some poor law authorities and voluntary organisations were calling it “boarding out”, using it as an official alternative to putting neglected children in workhouses or orphanages. [vii]

It’s possible that some small financial arrangement might have been made for Violet’s care, as was sometimes done in private fostering at the time. However, given the social status of the families involved, it seems more likely that Ann simply took her niece in out of familial duty rather than for payment.

We can hope that Violet had a reasonably happy childhood, but it is unlikely that she had much contact with her father, siblings, or other family members. Even though she was growing up just a few miles away, opportunities for contact would have been limited.

By the time of the 1921 census, 14-year-old Violet had left school and was working in Marks & Spencer’s Original Penny Bazaar, located in Arch 574 on Brixton’s Station Road. For a girl who had grown up with very little stability, the bright, bustling bazaar must have been both bewildering and exciting.

Opening in 1903, it was the company’s first London store.[viii] Nestled in the arches beneath the railway station, the “Original Penny Bazaar” displayed its goods front and centre, enticing South London shoppers into making a purchase – or three.

Marks & Spencer, which still exists today, over 120 years after its founding, began as the partnership of Michael Marks, a Jewish immigrant from Russia fleeing Tsar Alexander II’s anti-semitic pogroms, and Yorkshireman Tom Spencer. Together, they created one of the most famous business partnerships in British retail history. Their secret was simple: customers could see and touch the goods. Unlike in most other shops of the day, there was no haggling. Their slogan was “Don’t Ask the Price, It’s a Penny”. [ix]

The shop sold everyday household items – paper-wrapped pins, needles and hairpins, buttons, handkerchiefs, darning wool, reels of cotton, soaps, sponges, cups, saucers, plates, egg cups, baking tins, and buckets. The first bazaars opened in industrial towns in the north of England, and their success soon led the company to spread across the rest of the country.

Brixton was the first London outlet, soon followed by others across the capital. By 1910, the Brixton Bazaar was the top performing branch, with a turnover of £9,367, well ahead of the second placed Liverpool, which turned over £7,305. With 144 pennies to the pound at the time, those sums give a sense of just how busy the Brixton store must have been.[x]

Michael Marks took a personal interest in the welfare of the staff, arranging wooden platforms for the girls to stand on in winter so their feet wouldn’t freeze, and providing gas rings for them to heat their lunches.

It was a prestigious first job for Violet. The company’s slogan, still painted in scarlet on the floor just inside the entrance, greeted every customer. An aisle about two metres wide allowed shoppers to inspect the goods while the constant clatter of trains overhead reminded everyone of the busy city outside. Violet would have been carefully trained to attend to each visitor, in keeping with the company ethos that all customers should be welcomed – whether they bought anything or not.

At the time, M&S did not provide the basic necessities of life, such as bread, bacon, tea, and sugar. Customers visited the bazaars for the “little extras” and, just as importantly, to enjoy a bit of fun browsing and “looking around”.

Violet’s teenage home in Meadow Place was one of a terrace of seventeen mid-Victorian two-storey brick properties, with another fourteen on the opposite side of a narrow street just off South Lambeth Road, Kennington, but Violet and her aunt did not have the luxury of a house to themselves. The 1921 census reveals that number 13 was home to four separate households:[xi]

- Annie and Violet, occupying two rooms.

- The Thripp family, Sidney, a painter and paper-hanger, his wife Florence, and their two sons, aged five and eight months, who occupied three rooms.

- Jane Bullock, a 66-year-old widow living in one room and still working from home as a needlewoman.

- Kate Stevens, a 30-year-old single woman of private means, also in one room.

There was likely only one shared outside toilet and no bath, and most of those houses have long since been demolished.

Meadow Place lay about two and a half miles from Brixton, a distance that meant a tram or bus ride each way. Despite being only fourteen, Violet would have worked long hours: 9am to 8pm Monday to Friday, and on Saturdays from 9am to 10:30pm, with just a ten-minute break for cocoa in the morning, and an hour for lunch. There was no special uniform, but girls were expected to dress neatly in dark clothes, and management placed great emphasis on the importance of clean hands.[xii]

Her teenage years were probably very much like those of other working-class girls in mid-1920s South Kennington and Vauxhall. The neighbourhood was a tightly packed grid of old Victorian terraces, many of them subdivided like Meadow Place, where families lived cheek-by-jowl and everyone knew each other’s business. Washing days often meant carrying buckets to the shared yard and taking a turn at the communal mangle; coal deliveries, the smell of paraffin heaters, and the constant rumble of trams along South Lambeth Road formed part of the daily soundtrack.

Despite the cramped conditions, there was a probably a strong sense of community. Street markets along Kennington Road, Lambeth Walk and Vauxhall bustled with stallholders calling out their wares. For working teenagers, leisure time was precious: perhaps a trip to the cinema, or, if someone nearby owned a wireless set, crowding around it to listen to the latest music, and of course Saturday night dances at church halls or local venues. A cheap tram fare made even the West End reachable for those with a little spare change.

It may have been at one of these dances that Violet met a young man only a few months older than her: George Edward Cooper, from Spring Gardens, just across South Lambeth Road. The two would quickly have found common ground: George’s father had died when he was young, and he and his older brother Ernest had spent periods in the local workhouse and residential schools until his mother’s later remarriage eventually brought the boys back into her new family home. On the 1921 census George was working as a messenger for Best Retailers of 121 Victoria Street.[xiii] By the mid-1920s he had become a “Railway Man”,[xiv] a respectable and steady occupation that carried the promise of advancement.

The marriage entry hints at the couple’s characters: George signing boldly and confidently, Violet taking great care to fit all her names neatly into the space available.

George and Violet’s family quickly grew. Between 1927 and 1939, they had five children, all born in Lambeth: George Richard in 1927, Gladys Florence in 1929, Ronald Ernest in 1931, Raymond in 1933, and finally Sylvia Bessie in 1939. Because these births fall within the last one hundred years – so one or more of the children may possibly still be alive – it is difficult to trace their subsequent lives in detail. Even so, the pattern of their early years tells us something about the household George and Violet were building: one in which children arrived steadily through the interwar years.

One possible hint to George and Violet’s troubled childhoods lies in the names they chose not to pass on. None of their daughters were given the names of either grandmother – Emma or Sarah Ann – nor of Violet’s foster mother, Annie. In working-class families of the early twentieth century, naming children after close relatives was still common. The absence of those names in the Cooper household may be meaningful, though their eldest son’s middle name, Richard, may well echo Violet’s paternal grandfather, Richard Mayhew.

Or perhaps the decision on children’s names was less about omission and more about intention. George and Violet may simply have wanted to start afresh, giving their children names that belonged wholly to their new family, rather than from their own complex pasts. Whatever the reason, the choice feels deliberate, as if George and Violet were trying to shape a different future for the next generation.

By the late 1930s, just over twenty years after the end of the First World War – believed by many to have been ‘The War to End All Wars’ – Europe was once again sliding towards conflict, and families were beginning to feel the strain. Towards the end of August 1939, a huge government campaign, known as Operation Pied Piper, was launched to encourage parents to send children from cities across the UK began evacuation plans to move children from cities to the perceived safety of the countryside. The exodus began on Friday 1 September, when thousands of children were sent to unfamiliar towns and villages, sometimes with siblings, sometimes alone.

On 29 September, the 1939 Register was taken, capturing the details of every member of the civilian population. The information was used to produce identity cards, ration books, and to administer conscription and direct labour. George and Violet appear on the register with their youngest, baby Sylvia, but their older children are absent.[xvi] It is quite possible they had already been evacuated, repeating in part the pattern of fractured families that both George and Violet had known in their own childhoods.

The first eight months of the war became known as the ‘Phoney War,’ as there was little fighting in the West while Germany concentrated its military efforts on Poland. In April 1940, the German forces invaded Norway and Denmark and pushed south towards the Netherlands and France. British troops were unable to hold them back, and the Netherlands, Belgium, and France quickly fell to the Nazis. Many British and French soldiers were evacuated from Dunkirk. Between July and October 1940, the Battle of Britain raged in the skies, and in September 1940 the German Luftwaffe began bombing British cities. It soon became clear that the war would affect all civilians, not just those directly involved in combat.

It is likely that once the bombing began, Violet and baby Sylvia were evacuated to Guildford in Surrey. George, employed as a Motor Driver Railway, Heavy Worker,[xvii] would have been considered an essential worker for the railways and remained in Lambeth to continue his duties.

Sadly, not long after their arrival in Guildford, Violet fell seriously ill with a brain tumour. She died on 5 September 1942 at the Warren Road Hospital, which had formerly been the local workhouse. The postal address was often used on official records, which is why the death certificate records her death at 10 Warren Road, Guildford. The certificate records the death of Lily Violet Dorothy Cooper, female, aged 36, of 3 Camellia Street, Wandsworth Road, SW8, wife of George Edward Cooper, general labourer.

The cause of death was certified as 1a Cerebral Tumour (astrocytoma) and the informant was her husband, George Edward Cooper, listed as widower, also of 3 Camellia Street, Wandsworth Road, who registered her death on 7 September 1942.

Violet’s premature death at just thirty-six left a family without a mother, and what became of George and the children is lost to the records. Her story – from orphaned baby to a young mother taken too soon, leaving a grieving husband and five motherless children – is one of the saddest I have encountered in my family history research.

After searching for her for over twenty years, I am thankful to have finally found Violet, my ‘missing Mayhew child’, and to be able to tell her story.

If you want to read Violet’s mother Emma’s story, you can find it here.

[i] from the personal collection of Peter Mayhew, Adelaide, Australia

[ii] Child mortality rate (under five years old) in the United Kingdom from 1800 to 2020 via www.statista.com

[iii] Emma Mayhew’s death certificate

[iv] 1911 census RG14PN358 RG78PN11 RD3 SD5 ED21 SN134

[v] Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England, via www.familysearch.co.uk

[vi] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P77/MTW/005 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[vii] History of Adoption and Fostering in the United Kingdom by Jenny Keating via http://www.oxfordbibilographies.com

[viii] Marks & Spencer 1884-1984: a centenary history of Marks & Spencer Ltd, the originators of penny bazaars by Asa Briggs, published in 1984 by Octopus Books, London, via www.archive.org

[ix] ibid

[x] ibid

[xi] 1921 census RG15/2064 Ed 17 Sch 290 Book 2064 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xii] Marks & Spencer 1884-1984: a centenary history of Marks & Spencer Ltd, the originators of penny bazaars by Asa Briggs, published in 1984 by Octopus Books, London, via www.archive.org

[xiii] 1921 census RG 15/2059, ED 12, Sch 122; Book: 02059 via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xiv] London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P85/Ban via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xv] Ibid

[xvi] 1939 Register; Reference: Rg 101/341f, via www.ancestry.co.uk

[xvii] Ibid