The first full military funeral ever held on Hayling Island[i] took place on Tuesday 19th August 1913 at St Mary’s parish church, a beautiful thirteenth-century building standing on the Island’s highest point – all of twenty feet above sea level.

Over 150 Boy Scouts formed a guard of honour, while the band of the Royal West Sussex Regiment played Chopin’s Marche Funèbre. The cortege led by a carriage drawn by four horses, bearing the coffin draped in a Union Jack, made its way to the historic churchyard as hundreds of islanders lined the narrow lanes. The service was conducted with Catholic rites, unusual but not unprecedented, since the Burial Laws Amendment Act of 1880 had permitted non-Anglican ministers to officiate in Church of England cemeteries.

As a military service, there were no hymns, but when the polished elm coffin was lowered into the ground, bugles sounded the Last Post, and three volleys were fired over the open grave. The coffin bore the simple inscription:

“Joseph Twohey, died August 15th, 1913: aged 74 years”

His death was reported widely across England – but why did Joseph merit such fame and ceremony?

From rural Ireland to the front lines:

Born in Castleconnell, County Limerick, Joseph Twohey was the son of a British soldier, and one of seven brothers – all of whom became soldiers. The last to enlist, Joseph joined the 14th Regiment of Foot in September 1853, declaring himself to be 16 years and 8 months old[iii]. This suggests a birth around January 1837, though later census returns and his death certificate point to 1838 or 1839. It’s entirely possible that Joseph, eager to follow his brothers into service, exaggerated his age to enlist. Eager to follow his brothers, Joseph may have added a year or two to qualify.

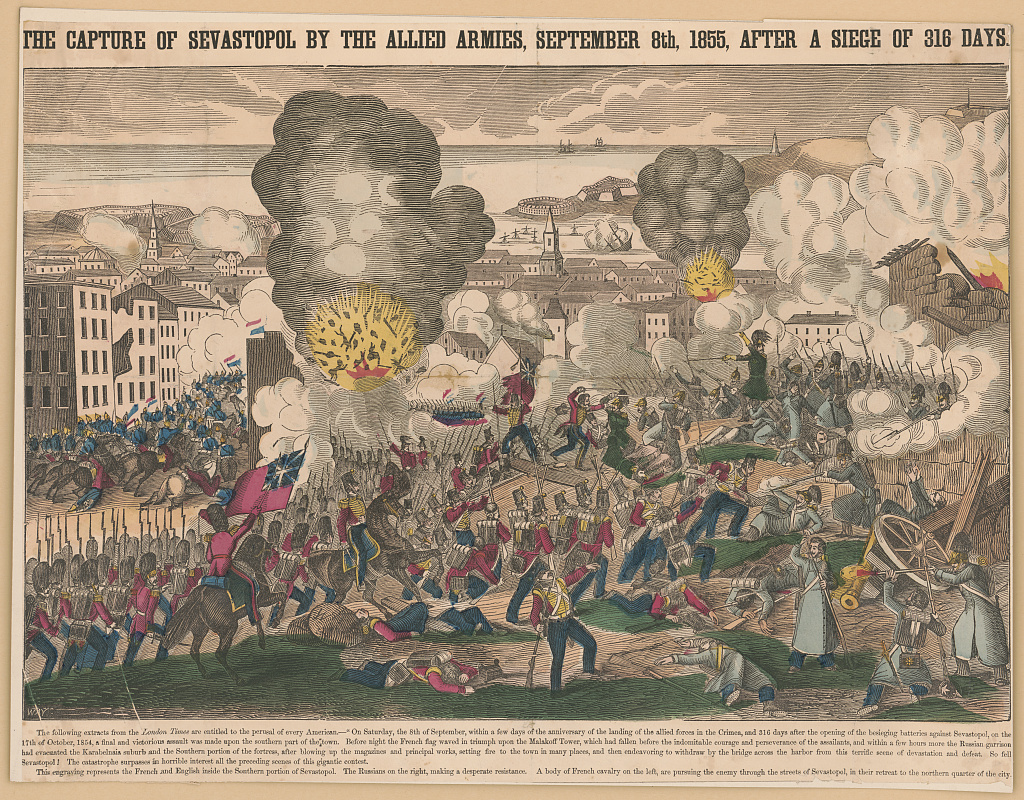

By New Year’s Day 1854, still a teenager, he was sailing for Malta, and within a year, he was in the trenches of the Crimean War. The conflict pitted Britain, France, Turkey, and Sardinia against the Russian Empire, with the appalling year-long siege of Sevastopol on the Black Sea.

Life in the siege lines was brutal. As a grim foretaste of the “war of attrition” that would define the First World War, French and British troops faced daily bombardments, and spent freezing nights digging and re-digging trenches with almost no proper equipment. Joseph suffered severe frostbite during this time.

Amid the mud and misery, he displayed extraordinary courage: under heavy fire he rescued a comrade who had lost both legs. Promoted to Corporal and recommended for the Victoria Cross, he never received the medal – but his bravery was undeniable. On 8 September 1855, he was among the first British troops to enter the Sevastopol after the Russian retreat. It was a brief moment of triumph overshadowed by horror and devastation – a pattern that echoed throughout his service.

A twist of fate in India

After the Crimea, Joseph returned to Portsmouth but in April 1856 was court-martialled for an unrecorded misdemeanour – possibly drunkenness – and reduced to Private.

The following year, he volunteered for service in India as the great uprising broke out, remembered in Britain as the Indian Mutiny of 1857 and in India as the First War of Independence. Native regiments rebelled, joined by local rulers and thousands of civilians, threatening to upend British power on the subcontinent.

Joseph, now with the 35th (Royal Sussex) Regiment, arrived in Calcutta at the height of the conflict. Ordered to Delhi, his regiment arrived too late to take part in the siege. Soon after, a crisis erupted at Arrah, where 18 civilians and 50 men of the Bengal Military Police were besieged by over 10,000 rebels. A relief column of 400 men from the 35th was dispatched – but at the last moment Joseph was reassigned to clerical duties due to the illness of the Orderly Clerk. That decision saved his life: of the relief force, only three men returned.

Joseph’s narrow escape may have marked a turning point. He went on to serve more than a decade in India, regaining the rank of Corporal and later Sergeant. Yet old habits died hard: in July 1866 he was again court-martialled for drunkenness and reduced to Private.

A quiet hero

The 35th returned to England in January 1868, and Joseph was soon promoted once more, serving at Aldershot and Portsmouth. In 1869, he married nineteen-year-old Catherine Dibben in St Mary’s Church, South Hayling – a place that would remain central to the family’s story.

By 1871 he was a recruiting sergeant in Northumberland, and ended his career in 1876 as Paymaster-Sergeant at Chichester. His medal collection included the Crimea Medal with clasp for Sebastopol, the Turkish Crimea Medal, the Indian Mutiny Medal, as well as long service and good conduct medals. In 1905, long after his retirement, he was further honoured with King Edward VII’s Medal for Meritorious Service, presented to him at a special parade of his old regiment in Chichester. Despite two court martials, his conduct was officially described as “very good.” His discharge papers record him as 5ft 7in tall, with a sallow complexion, grey eyes, and brown hair.

After retiring, Joseph and Catherine settled in Sussex and raised two daughters, Norah and Evelyn. They also welcomed Joseph’s brother Thomas, a retired army musician also from the 35th Foot, into their household.

Family life brought joy and sorrow. Norah married in 1897 but soon fell ill with tuberculosis; her marriage collapsed, and she died two years later at her parents’ home. Thomas died in 1902. Evelyn married in 1903 and lived for a time in Italy, returning to England as Europe grew unsettled. Tragedy struck again in January 1913 when Evelyn’s only son died of meningitis and was buried in St Mary’s churchyard, close to his aunt Norah and great-uncle Thomas.

Joseph died at home six months later, and the rest is history.

Despite his medals and accolades, Joseph rarely spoke of his wartime service.

“I’ve seen such terrible things. I’d rather forget than recall them.”

You can read Joseph’s father James Twohey’s story here

[i] Details from an extensive obituary published in the Hampshire Post and Southsea Observer (Portsmouth) – 23 Aug1913 via www.findmypast.co.uk last accessed 3 Oct 2025

[ii] Daily News (London) – 18 August 1913 via via www.findmypast.co.uk last accessed 3 Oct 2025

[iii] The National Archives Ref GBM_WO97_2126_108

[iv] Image in the public domain via Library of Congress Prints and Photographic Division, Washington DC, USA https://loc.gov/pictures/resource/pga.08519/ last accessed 3 Oct 2025

[v] St Mary’s Church, Church Road, file available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication via commons.wikimedia.org last accessed 3 Oct 2025