Scant records remain of my third great-grandfather’s life, but the British Army Royal Hospital Chelsea Pension files help trace the outline of a hard and remarkable journey – from rural Ireland to Imperial outposts in the Indian Ocean and India. Discharged as no longer fit for service at just 28, he returned home to begin a new life in Limerick, Ireland.

One Irishman’s journey through the Empire

James Twohey was born around 1794 in Castleconnell[i], a picturesque village on the River Shannon, six miles north of Limerick. Once a popular spa town famed for its healing waters, Castleconnell was a world away from the empire James would one day serve.

In the wake of the bloody Irish Rebellion of 1798 – inspired by revolutionary movements in France and America – the Irish parliament was abolished by the 1801 Act of Union. Ireland became part of the new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with power transferred firmly to Westminster.

Meanwhile, back in England, the Industrial Revolution was radically reshaping society. Large numbers of rural agricultural workers moved to overcrowded cities in search of employment in factories or as builders’ labourers, often becoming physically diminished by poor diets, pollution, and relentless overwork. In contrast, rural Ireland – though economically deprived – continued to produce strong and healthy young men,who were ideal candidates for military service.

Recruiting sergeants scoured the Irish countryside and, for many young men, enlistment offered the only route out of poverty. When James joined the British Army at the age of 16, he was described as 5 feet 6 inches tall, with fair hair, grey eyes, and a fair complexion[ii]. A labourer by trade, he was typical of the Irish recruits who made up nearly 40% of the British Army at the time – resilient, practical, and hungry for a more secure life.

James “took the King’s shilling” and agreed to serve as a Redcoat in His Majesty George IV’s Army for life – effectively until death or incapacity. In return, he was issued with a uniform (which he had to pay for), three meals a day, and a small but regular wage. But the real price of enlistment was surrendering control over his own future. Once James had signed on the dotted line, he could be sent anywhere in the world, at any time, at the King’s pleasure – whether to fight, to garrison, or simply to endure. There were no guarantees, only orders.

After a year of training, James was posted to the 86th (Royal County Down) Regiment of Foot and sent to the island of Mauritius, recently captured from the French. In 1812, the regiment was posted to Madras (now Chennai) on the southeast coast of India. They were stationed at Fort St George and the nearby garrison town of Poonamallee, as part of the British East India Company’s military machine — soldiers serving not only Crown and Country, but the profits of a vast commercial empire that sought to control trade, territory, and taxation across the subcontinent.

Despite the intense heat and seasonal monsoons, James would have worn a tight scarlet wool tunic with white facings, a tall black shako (military cap) adorned with regimental insignia, light coloured wool trousers, and black leather ankle boots. It was the proud and unmistakable dress of a British Redcoat – but hot, heavy, and wholly unsuited to the tropical climates of Mauritius and Madras.

Garrison life in 19th-century India

James was stationed for a time at Poonamallee, a garrison town near Madras (now Chennai), where the British maintained a hospital, barracks, and ordnance depot. Though technically just outside the city, the station was isolated and brutally hot, and living conditions were far from comfortable.

One officer, writing a decade or two later, described the place with dismay:

“If the walls of the old fort at Poonamullee were knocked down, and the whole levelled and exposed, the place would be tolerable… The officers’ quarters are wretched — little bits of pigeonholes and so hot that anyone residing within them ought to be grilled to death.”[iv]

The soldiers stationed there faced poor air circulation, stifling heat, unsanitary conditions, and a lack of meaningful activity. Disease was ever-present, and morale was often low.

For James and his comrades, it was a world away from Castleconnell – monotonous, alien, and physically punishing.

James remained in the region for nearly a decade. In March 1819, he transferred to the 69th Regiment of Foot, then stationed at Cannanore on India’s Malabar Coast — a central hub in British military operations.

Though James served before Florence Nightingale’s pioneering reforms, her later analysis of British Army health records in India[v] sheds important light on the conditions he and thousands of others likely endured. Based on data from the 1850s and 1860s, Miss Nightingale found that soldiers were confined to their barracks for as much as twenty hours a day, with little to occupy their time beyond smoking, gambling, or drinking to pass the oppressive heat.

Disease was rampant. Cholera, dysentery, fevers, and liver disease stalked the cramped quarters, where men slept and sweated in overcrowded huts with poor sanitation and little ventilation.

Miss Nightingale identified the chief causes of military sickness as:

- Bad water

- Bad drainage

- Filthy bazaars

- Want of ventilation

- Surface overcrowding in barrack huts and sick wards.

While her findings came decades after James’s discharge, there is little reason to believe things were any better during his service. If anything, conditions in the 1810s and 1820s may have been worse – with little medical oversight, no systemic hygiene measures, and a military bureaucracy more focused on obedience than wellbeing.

A long way from home

For soldiers like James, the hardship of military life wasn’t only physical – it was emotional, too. Enlisted men stationed overseas were granted no home leave. Communication with loved ones was painfully slow. Letters – for those who could read and write – might take months to arrive, if they arrived at all. Entire lives could unfold and end back home before news ever reached the barracks. There were no photographs yet to preserve family faces as photography would not be invented until the late 1830s. For men like James, memory was the only connection to home: a riverbank in Castleconnell, a sibling’s voice, a mother’s face – all slowly fading with each passing year.

Loneliness was a quiet constant. Surrounded by men of different counties and creeds, exposed to strange climates and languages, and hemmed in by the rigid structure of garrison life, many soldiers experienced what today we’d call profound isolation. Some turned to drink. Others fell into silence. And a few, like James, simply endured.

Most would never return home. For those who did, it was often as strangers — changed by distance, time, and the long shadow of empire.

“Disabled from his own misconduct”

James’s army service ended abruptly in January 1822. At just 28, after eleven years and 274 days in the ranks, he was discharged from the 69th Regiment of Foot “in consequence of rupture” [vii] – likely a hernia or torn tendon, both common injuries among soldiers engaged in manual labour, drill, or overexertion.

But the official record included a more damning comment:

“Disabled from his own misconduct.”

What that means is unclear, but it casts a shadow over the nature of his injury. It may have been sustained during a drunken fall, a fight, or some other preventable incident – common enough in the boredom and hardship of garrison life. The phrase was used broadly by the Army to deny responsibility for a soldier’s incapacity, and it likely affected the level of pension James would receive.

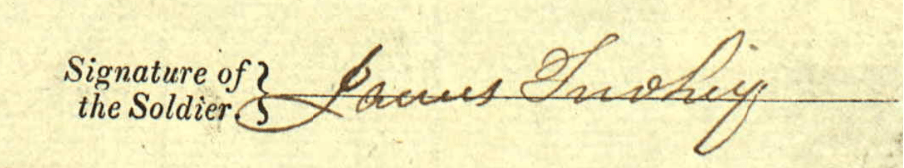

Despite the stain on his record, James signed his discharge papers with a clear and confident hand – suggesting that he was literate and capable. He had survived more than a decade of service in some of the most unforgiving postings the Empire had to offer. And now, suddenly, he was no longer the Army’s responsibility.

James was shipped back to England, landing at Gravesend, Kent, on 25 June 1822. He then travelled to London and was accepted by the Royal Hospital Chelsea as an out-pensioner the following month. His daily pension was 9d per day[viii] – a modest but crucial lifeline – and he soon returned to Ireland.

Despite his injury, James married and fathered at least seven sons – all of whom followed him into military service. His son Joseph, born around 1839, would later be described in his obituary as “the last survivor of a family of soldiers.” But Joseph’s story is one for another time.

Not completely forgotten

James Twohey died in Limerick on 7 December 1866[ix] aged 72 – a good age for a man who had crossed oceans, endured India’s garrisons, and returned to live out more than four decades after the army had deemed him unfit for service.

He never rose through the ranks nor was awarded any medal. His is not a story of battlefield glory, but of quiet fortitude – a young Irishman who served, suffered, and quietly returned home.

Forgotten by history, perhaps – but not by me, his third great-granddaughter. Having uncovered his story after more than 200 years, I can now honour his place in our family story – and by sharing it here, carry his legacy forward.

[i] Royal Hospital Chelsea: Soldiers Service Documents WO97/823 via www.fold3.com last accessed 11 Jul 2025

[ii] Ibid

[iii] Historical record of the Eighty-sixth, or the Royal County Down Regiment of Foot: containing an account of the formation of the regiment in 1793, and of its subsequent services to 1842 by Richard Cannon, published in 1842 by J.W. Parker, London, via www.archive.org.uk last accessed 16 Jul 2025

[iv] Ten Years in India by Captain Albert Hervey published by William Shoberl in 1850 via www.archive.org last 11 Jul 2025

[v] Observations on the evidence contained in the stational reports submitted to her by the Royal Commission on the Sanitary State of the Army in India by Florence Nightingale published 1863 via www.archive.org last accessed16 Jul 2025

[vi] Ibid

[vii] Royal Hospital Chelsea: Soldiers Service Documents WO97/823 via www.fold3.com last accessed11Jul 2025

[viii] Royal Hospital Chelsea, Pension Admission and Discharge Records > Disability and Out-Pensions, Admissions | Piece 032: 1821-1822 (Cavalry and Infantry) WO 116/022 via via www.fold3.com last accessed11Jul 2025

[ix] Royal Hospital Chelsea: Regimental Registers of Pensioners > 60th-69th Foot > 1814-1857 WO 120/61 via www.ancestry.co.uk last accessed11 Jul 2025