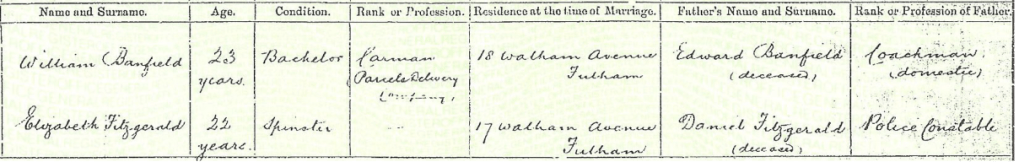

For over fifteen years I could find no trace of my great-grandfather before his marriage to his neighbour Elizabeth Fitzgerald. The ceremony took place in St Thomas’ Roman Catholic Church, Fulham, in 1893. Trusting the information given on their marriage record, I assumed I was searching for William Banfield, born around 1870, whose father was Edward Banfield, a domestic coachman who had died sometime before 1893[i].

I was wrong. William Banfield had been born Evan William Edward Wackrill.

About three years ago, I began to unravel the mystery behind this man and his early life. Evan William Edward Wackrill was, in fact, the eldest son of Edward Wackrill, a groom, and his wife Leah[ii]. But when Evan was just six years old, his father died – leaving Leah a young widow with three small children, no home, and few options. This is her story:

Who was Leah?

As I peeled back the layers of her story, I found myself drawn into the bleak realities of 19th century poverty and the quiet desperation that shaped the lives of women like Leah. Her choices – some painful, some courageous – began to make sense only when seen in the context of a society that shared little sympathy or support to those who had fallen through the cracks.

To understand Leah, we must first step back further in time – to her own beginnings.

My 2nd great-grandmother, Leah Ellen Mayo, was born in Chelsea in June 1847[iii], the third child and second daughter of William Mayo, a carpenter, and his wife, also Leah (née Burridge). The family’s life reflected that of many manual labourers’ in mid-19th century England – often moving to find work where they could and, by the time of the 1851 census they were living in Chiswick, West London. [iv] Little Leah, aged 3, appears alongside her parents, her older sister Mary, younger brother James, and a cousin, Jane Hocker, aged 10. Leah’s eldest brother, William James, had died the previous year[v].

Three years later, Leah’s mother died of consumption – known today as tuberculosis – after six months[vi] of suffering from this wasting illness. Not long afterwards, William remarried.

By the time Leah was thirteen, she was in domestic service. She had found work as a live-in servant with Mr George Flint, his wife, and their five children in Brixton, South London. [vii] With only one other servant in the household – listed as a governess looking after the children – Leah’s role probably involved a mix of cleaning, child-minding, and assisting in the kitchen, perhaps in exchange for little more than bed, board, and basic training. Her 16-year-old sister Mary was also in service nearby, with a family in Clapham.[viii] Their younger siblings, James (aged 11) and Celia (9) remained with their father and stepmother,[ix] just a couple of streets away across Clapham High Street

George Flint, Leah’s employer, was a gentlemen’s and boys’ outfitter and hosier, with premises in the fashionable Cheapside in the City of London. However, in June 1861, his business hit trouble. A customer brought a court case against him, accusing Mr Flint of substituting inferior goods.[x] Within a month, the business went into voluntary liquidation, and he was declared bankrupt.

Leah presumably secured another position after this, but there’s no trace of her until her marriage to Edward Wackrill, a coachman, on 11th October 1869. Their wedding took place in the historic church of St Mary-at-Lambeth, next door to Lambeth Palace. The church is today home to the Garden Museum.[xi] The witnesses to the marriage were Ed Powell and Ann Miles, who appear to have had no family connection to either bride or groom – perhaps fellow servants, housemates, or simply available parishioners asked to stand in.[xii]

Eleven months later, on 17th September 1870, Leah gave birth to her first child – my great-grandfather – Evan William Edward Wackrill. He was born in Robert Street, Mayfair (now Weighhouse Street[xiv]), a short walk from Hyde Park. At that time, his father Edward was employed as a groom,[xv] responsible for the care of horses, so it’s likely the young family were living in modest rented accommodation close to the stables in Cock Yard (now St Anselm’s Place)[xvi].

The baby’s three given names formed a tribute to his paternal grandfather Evan, maternal grandfather William, and his father Edward.

Two years later, in 1872, Leah gave birth to a second son, Thomas Uriah, in Hackney, East London. The brothers were baptised together in November that year at St Philip’s Church, , Dalston.[xix] The family had moved to the more suburban surroundings of Dalston, where Edward now worked as a horsekeeper.

In Victorian London, men like Edward – grooms, coachmen, and horsekeepers – were often at the mercy of short-term employment and seasonal contracts. Families moved frequently to stay close to the stables or yards where horses were kept, and many central districts were undergoing redevelopment. For working-class Londoners like the Wackrills, mobility was not a sign of social climbing but a practical response to economic necessity.

By July 1874, Edward and Leah, were living in Paradise Street, Lambeth, when they welcomed a daughter, Annie Ellen[xx]. But tragedy soon followed. In the spring of 1876, little Annie died of pneumonia at the age of 21 months at home in 53 Great Tipton Street, close to Hanover Square.[xxi] Only weeks later, Leah gave birth to another son, Edward Augustus, also at Tipton Street[xxii].

Then, in February 1877, disaster struck again. Edward Wackrill died of smallpox at the age of 31.[xxiii]

Leah’s Struggle Begins

Leah was only 29 years old when she found herself a widow with three small children – Evan aged six, Thomas aged four, and baby Edward not yet a year old. In the London of the late 1870s, support for women in her position was sparse and unreliable.

It’s likely that the home she shared with her husband was tied to his employment. Edward worked as a groom or horsekeeper, a live-in role that often came with lodgings in a mews or stable yard. After his death, Leah would not only have lost his income but quite possible the roof over her head. Within days or weeks, she may have found herself standing on the street with three young children and nowhere to go.

There is no sign that Leah’s extended family stepped in to help. Perhaps her siblings had drifted away, or perhaps they, too, were struggling to make ends meet. With Edward’s work taking the family from Mayfair to Dalston to Lambeth and then back to Westminster, Leah had moved frequently, rarely staying long enough to build a local support network. If she had friends, they were likely just a transient – always a change of job or a landlord away from vanishing.

In theory, widows could apply for assistance under the Poor Law system. The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act had aimed to reduce dependency by making the workhouse a deterrent – a place of last resort. It did allow for some modest help outside the workhouse, known as “out-relief,” especially for widows with legitimate, dependent children. But this was rarely generous and often came with strings attached. [xxiv]

Although workhouses were not technically prisons and entry was usually voluntary, they were feared. Families could be separated upon admission, housed in different wards, forbidden to speak freely, and subjected to strict routines. It is perhaps telling that there is no evidence Leah and her children ever entered one together.

Instead, Leah may have made the heartbreaking decision that her elder boys would be better off in the care of a Poor Law boarding school than struggling alongside her in near-destitution. By the time of the 1881 census, her two eldest sons – Evan and Thomas – were living apart from her, recorded as “inmates” at the West London District School in Ashford, Middlesex. [xxvi]

This was a large residential institution for children supported by the Poor Law – not a prison, but not a home either. It housed around 800 boys and girls: orphans, illegitimate infants, those removed from neglectful homes, and others – like Evan and Thomas – whose families had fallen on hard time.

Despite the Dickensian image of Victorian children’s institutions – bleak dormitories, harsh discipline, loveless routines – the reality at Ashford was perhaps more nuanced. Conditions were basic, but many children received more consistent nourishment and medical attention than they had known at home. Education was compulsory and reasonably consistent, and the daily regime aimed to prepare children for respectable employment.[xxvii]

Still, the emotional cost was steep. For a mother like Leah, admission of her sons meant not just the loss of daily contact but also legal custody. Once a child entered the Poor Law system, getting them back was difficult, emotionally, administratively, and sometimes financially. A fee might be required for a child’s release, and even then, a mother had to prove she could provide a stable home. [xxviii]

While Evan and Thomas were in Ashford at the time of the census, Leah and her youngest son, four-year-old Edward, were living in a cramped room at 11 John Street, Fulham. They shared the tiny two-up-two-down house with William Baker, his wife, and their six children, aged between nine and nineteen.[xxix] A housing inspector writing in the 1880s described John Street as a place where houses held “20 people… counting children,” surrounded by “mess, bread paper, old tins,” and outside were “rough youths playing with trouser buttons.” Women wore “sack aprons” and children were “dirty, well fed, sore eyes.” [xxx]

It was in this setting – harsh, unsanitary, and barely private – that Leah scraped together a living.

The 1881 census lists her occupation as “charwoman” – a term used for women who took on casual cleaning in other people’s homes. It was exhausting and poorly paid, with no job security and little chance of improvement. For widowed mothers like Leah, the basic challenge of survival loomed large each day.

There’s a strong possibility that, in order to supplement her earnings, Leah turned to what was euphemistically called “dollymopping”. A dollymop was a respectable woman who occasionally exchanged sexual favours for money. In the 19th century, this kind of informal sex work was widespread among working-class widows and single mothers with few alternatives. Soliciting in itself was not illegal; what the authorities sought to control was public order, not the hidden strategies of desperate women.

The chaplain of Millbank Prison, London’s main penal institution for women at the time, interviewed over 16,000 female inmates. His observations revealed a stark pattern: many widows resorted to occasional prostitution, not out of moral failing, but out of sheer necessity – to feed their children, to avoid the workhouse, to keep a roof over their heads. [xxxi] For Leah, who had lost her husband, her home, and perhaps much of her social support network, this kind of work may have been one of the few options that allowed her to retain even a shred of agency over her circumstances.

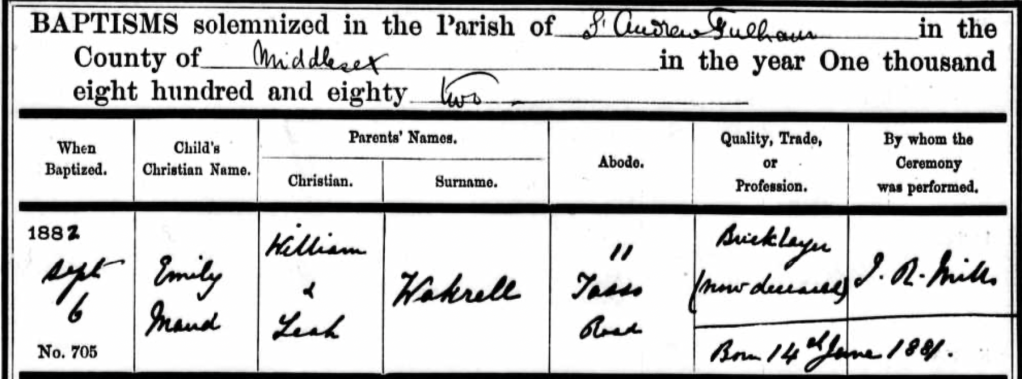

Shortly after the 1881census, Evan and Thomas must have left Ashford and briefly returned to their mother. Then, on 12th June 1881, Leah gave birth to another child – a baby girl – at home in John Street. Just over three weeks later, she registered the child under the name of Emily Maud Wackrill. In doing so, Leah told a deliberate untruth: she named her long-deceased husband, Edward Wackrill, as the father – even though he had died four years earlier.

This quiet act of forgery speaks volumes. The registrar would have reminded her that providing false information was a criminal offence under Section 40 of the 1874 Births and Deaths Registration Act, punishable by a fine or even imprisonment. And yet Leah still chose to sign the register with this fiction. It suggests how important it was to her, in that moment, to preserve some semblance of respectability – for herself and for her children.

The stigma attached to illegitimacy was severe. For a woman already living in poverty, being seen as a fallen or ‘unchaste’ woman could mean the difference between charity and condemnation.

I imagine Leah tried her hardest to keep her family together, but the strain must have been relentless. The physical exhaustion of manual work, the emotional toll of bereavement, and the daily scramble to feed and shelter her children, would have worn down even the most determined spirit.

On 24th August 1882, Leah made a heartbreaking decision: all three of her sons, Evan, Thomas, and six-year-old Edward – were admitted to the West London District School in Ashford.[xxxii] Leah kept her baby daughter Emily with her – perhaps because she was still nursing, or simply too young to be parted from her mother. That decision to send her sons away, leaving her with just a toddler in her arms, must have been agonising.

A week later, Leah and baby had moved to nearby Tasso Road, and on 2nd September 1882, she took the child to be baptised at the local Anglican church, St Andrew’s, in Fulham.[xxxiii] Once again, Leah chose to bend the truth – this time before a man of God. She gave the father’s name as William Wakrell [sic], a bricklayer, now deceased. It was a complete fabrication. She also gave Emily’s date of birth as 14th June, rather than 12th – perhaps a simple error, or another small alteration to help preserve appearances.

It’s hard not to wonder what was going through Leah’s mind as she stood at the font. Was this about respectability – giving her daughter a name and a ‘father’ to carry forward in official records? Or did she fear that, without a legitimate, baptised identity, her child might not be fully accepted in the eyes of the Church, or even by God? In a time when morality was tightly bound to social standing, perhaps this quiet act of baptism was Leah’s way of shielding her daughter not just from earthly judgement, but from spiritual exclusion too.

Meanwhile, Leah did not give up on her sons. As soon as she was able, she likely returned to work, raising money however she could to try and bring them home. Edward was discharged from the school on 11th January 1883, followed by Evan and Thomas on 7th October 1884. Slowly, and against the odds, the family was reunited.[xxxiv]

Hardship in Fulham’s Shadowed Streets

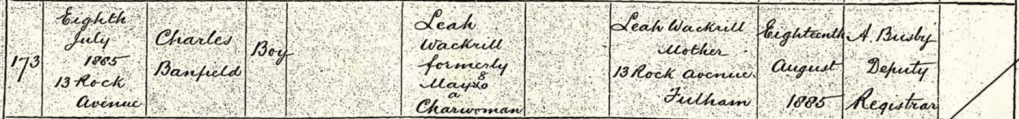

Somehow, Leah managed to hold her little household together. They moved to a new address: 13 Rock Avenue, Fulham, and on 8th July 1885, Leah gave birth to another son. This time, at the registrar’s office, she left the father’s name and occupation blank. She named her child Charles Banfield Wackrill and, once again, gave her own occupation as “charwoman”.[xxxv]

The choice of “Banfield” as a middle name is intriguing. Leah may have known who the child’s father was, and perhaps Banfield was his surname – yet there is no clear trace of a likely man with that name living in the local area at the time. It’s also possible that Leah simply chose the name for its sound or for a private significance known only to her. In any case, by omitting the father’s identity altogether,she took steps to protect both herself and her child – a choice that reflects the ongoing precarity of her situation.

In Victorian London, the risks of unexpected pregnancy loomed large for women generally, but this was an especial risk to those who, like Leah, may have relied on informal or transactional relationships to survive. Contraception was unreliable and hard to come by, and women bore the consequences of relationships that were often unequal and unstable. And yet, despite the judgment and hardship, Leah brought Charles into the world and raised him alongside his siblings. Her quiet persistence in keeping her family together speaks volumes about her courage and determination.

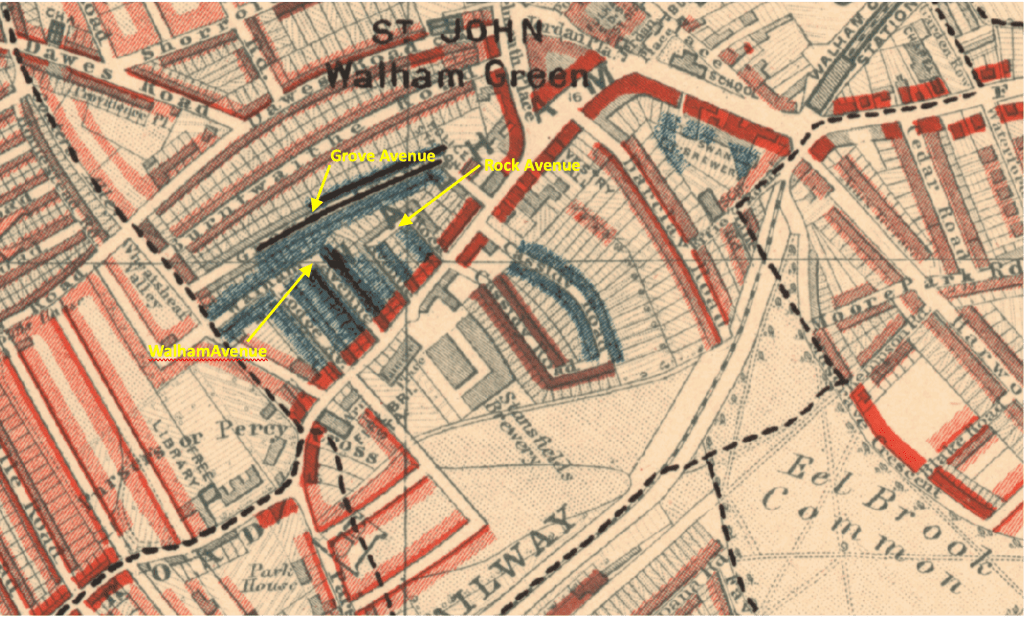

At last, Leah and her children appear to have found a kind of fragile stability in the streets around Walham Green (now Fulham Broadway), remaining in the area for close to a decade. However, they seem to have moved frequently from one lodging to another. Tracing their steps through historical records, the family can be found in Rock Avenue, Grove Avenue, and Walham Avenue. Despite their bucolic names, these were not leafy suburbs but a warren of narrow passageways and overcrowded tenement buildings. Homes were packed back-to-back with little or no open space, no indoor plumbing, and shared outdoor privies. Water came from communal pumps or standpipes. Most residents were extremely poor, often unemployed or scraping by on casual work.[xxxvi]

According to Charles Booth’s poverty maps, these streets were shaded dark blue for “Very poor, casual. Chronic want”, or black for “Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal”.[xxxvii] Grove Avenue, for example, was home to “labourers, costers, bus workers, and the lowest class of prostitutes as in the neighbouring avenues”, while Walham Avenue was described in stark terms: “windows broken, patched, doors open, women and girls in frayed skirts and hatless, foetid smell of dirt, costers barrows, vile place.”[xxxviii]

Another Mouth to Feed

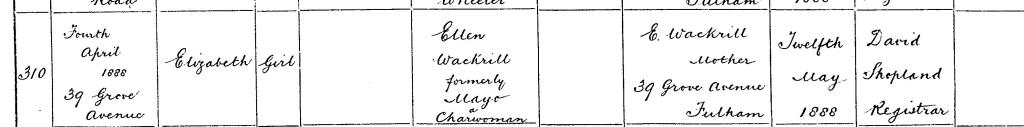

Less than three years after Charles was born, Leah gave birth to another daughter, Elizabeth Wackrill, on 4th April 1888 at 39 Grove Avenue, Fulham. Once again, no father was recorded on the birth certificate.

This time, however the mother was named not as Leah but as “Ellen Wackrill, formerly Mayo” – drawing on Leah’s middle name. Whether this was a deliberate decision or an administrative error is impossible to say. Either way, Leah did not name a father and listed her usual occupation: charwoman.

Her continued use of the surname Wackrill for all her children – regardless of their paternity – may reflect a desire to present a unified family identity and some semblance of respectability. It may also point to a deeper emotional connection with the life she had once known, before widowhood and poverty reshaped her world.

Tragically, little Elizabeth died of bronchitis at just 14 months old, at 6 Grove Avenue. Her death certificate states her mother is “Emma Wackrill”, a charwoman, who was present at the death. Notably, the same registrar had recorded both Elizabeth’s birth and Emily’s some years earlier. Whether Leah deliberately gave a different name, or the registrar simply misheard her, we cannot know. But once again, her identity – Leah, Ellen, Emma – appears fluid, shaped by necessity and anonymity.

By the early 1890s, Leah and her family had spent several years in the dense streets around Walham Green. Though they still lived in crowded lodgings, the records begin to suggest a degree of stability – alongside the emergence of a new surname.

The Emergence of ‘Banfield’

On 1st September 1890, nine-year-old Emily Banfield enrolled at Halford Road School in Fulham[xl]. Her date of birth was recorded as 12 June 1881 – exactly matching that of Emily Wackrill, Leah’s daughter. The school register listed the child’s mother as “Emily Banfield”, residing at 58 Walham Avenue. It also noted that young Emily had previously attended Ackmar Road School, and that she left Halford Road in April 1892, likely transferring again.

This is the first clear record of a family member using the name Banfield. It seems a deliberate shift, perhaps chosen to offer a fresh start, a new respectability, or simply a protective layer of anonymity. For a family that had lived much of the last thirteen years under the weight of poverty, stigma, and official scrutiny, the name may have offered a chance to step beyond the past.

By the time of the 1891 census, taken just months later, Leah was living at 28 Walham Avenue[xli]. Now 45, she was still working as a charwoman, listed under her married name Leah Wackrill. Her household included her five surviving children – Evan (20), Thomas (18), Edward (14), Emily (9), and Charles (5) – all recorded as Wackrill. The family shared their home with two other households, totalling 17 people under one roof.

A Family Rewrites Itself

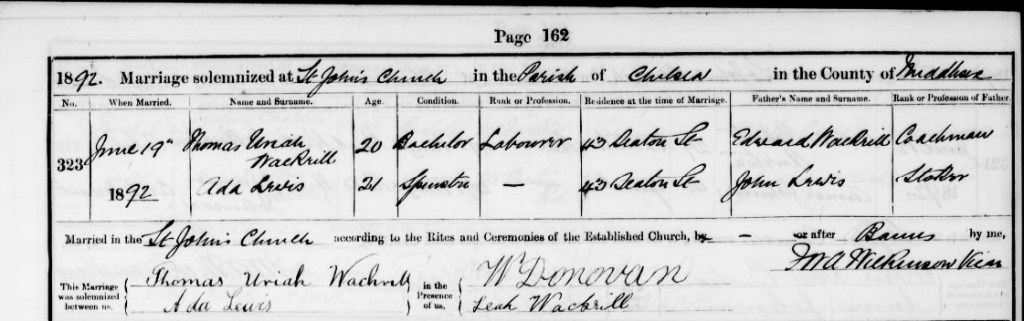

Just over a year later, on 19th June 1892, Leah’s second son Thomas Uriah Wackrill married Ada Lewis[xlii]. Their marriage certificate lists the groom’s father as Edward Wackrill, coachman, briefly reviving the name and identity of a long-dead parent. Leah signed as a witness, again using the Wackrill name in formal settings.

But only months later, on 28th October 1892, Thomas was arrested – this time he gave his name as Thomas Banfield[xliii]. The Banfield alias was clearly gaining ground within the family, particularly among the younger generation.

Leah’s first grandchild, Charles Edward John Wackrill was born to Thomas and Ada on 23rd October 1892 and baptised under that name just weeks later[xliv]. But, when he sadly died of measles and bronchitis in June 1894, his death was registered as Charles Edward John Banfield[xlv] – marking yet a further shift toward the new family identity.

A New Life in Acton

By the mid-1890s, the Wackrill name had all but disappeared from official records. After more than a decade in the overcrowded alleys of Walham Green, Leah, now in her late forties, relocated with her younger children to Acton, west of Shepherd’s Bush. For her, the move and new surname likely signified more than just a change of address. They may have offered a form of protection, a measure of dignity, and a way to escape the long shadow cast by poverty, widowhood, and illegitimacy.

By this time, Leah’s eldest son Evan, now going by ‘William Banfield’, had married his neighbour Elizabeth Fitzgerald, and begun a family of his own. His marriage record was the starting point of my search. For years, I believed I was looking for a man named Banfield, the son of a coachman – and in sense, I was. But the real story lay behind the name: a family forged through reinvention, secrecy, and resilience in the face of adversity.

Leah’s Final Years and Legacy

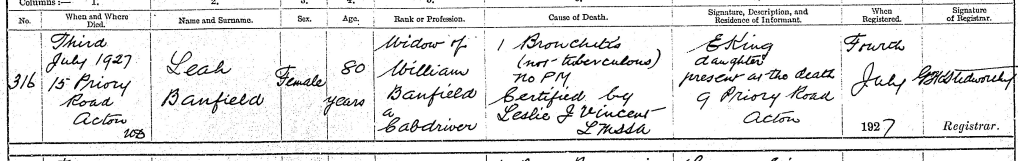

And Leah’s story didn’t end in obscurity. She lived on for more than thirty years after the move to Acton. Her death, at the age of 80[xlvi], was registered by her daughter Emily, under the name Leah Banfield, widow of William Banfield, a cab driver – a man who, as far as I can tell, never existed.

It was the final invention in a long line of careful fictions. Perhaps William Banfield had come to represent more than just a name. He may have embodied the kind of life Leah had once hoped for – a life of order, dignity, and respectability. In death, as in life, she presented herself not as a woman undone by loss and hardship, but as the widow of a working man.

Her children and grandchildren carried the Banfield name into the next century. Some, like my great-grandfather William, built new lives and left the hardships of their youth behind. Others struggled. But all were shaped by Leah’s determination, resourcefulness, and quiet defiance of the roles society had assigned her.

For many years, I searched for the Banfield family. And in the end, I found something more:

A story of reinvention.

A legacy of endurance.

And a courageous woman who never stopped fighting to keep her family together – even if it meant rewriting the truth.

You can read Leah’s husband Edward Wackrill’s tragic story here

[i] William Banfield and Elizabeth Fitzgerald marriage certificate in the author’s personal files

[ii] Evan William Edward Banfield’s birth certificate in the author’s personal files

[iii] Leah Ellen Mayo’s birth certificate in the author’s personal files

[iv] 1851 England Census – Class: HO107; Piece: 1699; Folio: 404; Page: 26; GSU roll: 193607 via ancestry.co.uk

[v] William James Mayo’s death certificate in the author’s personal files

[vi] Leah Mayo’s death certificate in the author’s personal files

[vii] 1861 England Census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 360; Folio: 35; Page: 1; GSU roll: 542622 via ancestry.co.uk

[viii] 1861 England Census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 368; Folio: 32; Page: 16; GSU roll: 542624 via ancestry.co.uk

[ix] 1861 England Census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 369; Folio: 27; Page: 16; GSU roll: 542624 via ancestry.co.uk

[x] Windsor & Eton Express 8 Jun 1861 via Findmypast.co.uk

[xi] St-Mary-At-Lambeth: A Medieval Hidden Gem via livinglondonhistory.com

[xii] Edward and Leah’s marriage certificate in the author’s personal files

[xiii] Lithograph by William Richardson in the public domain via commons.Wikimedia.org last accessed 6 Jun 2025

[xiv] British History on Line > Robert Street via http://www.british-history.ac.uk last accessed 4 Jun 2025

[xv] Evan William Edward Wackrill’s birth certificate in the author’s personal files

[xvi] British History on Line > Robert Street via http://www.british-history.ac.uk last accessed 4 Jun 2025

[xvii] 1871 England Census RG 10/152/95/16

[xviii] Extract from Richard Horwood’s 1799 map of London via www.romanticlondon.org last accessed 6 Jun 2025

[xix] London, England, Church of England Births & Baptisms, Hackney, St Philip Dalston, 1870-1922 via ancestry.co.uk

[xx] Annie Ellen Wackrill’s birth certificate in the author’s personal files

[xxi] Annie Ellen Wackrill’s death certificate in the author’s personal files

[xxii] Edward Augustus Wackrill’s birth certificate in the author’s personal files

[xxiii] Edward Wackrill’s death certificate in the author’s personal files

[xxiv] The implementation of the Poor Law via http://www.victorianweb.org

[xxv] Wellcome Collection gallery Ref: L0006802 CC BY 4.0 via commons.wikimedia.org last visited 07/06/2025 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35874132

[xxvi] 1881 England census – Class: RG11; Piece: 1327; Folio: 149; Page: 13; GSU roll: 1341322 – via ancestry.co.uk

[xxvii] Foundling Hospital – the health of London children via www.cityoflondon.gov

[xxviii] Entering and Leaving the Workhouse. https://www.workhouses.org.uk/life/entry.shtml

[xxix] 1881 England census – Class: RG11; Piece: 67; Folio: 94; Page: 13; GSU roll: 1341015 – via ancestry.co.uk

[xxx] George H. Duckworth’s Notebook: Police District 28 [Kensington Town], District 29 [Fulham], District 30 [Hammersmith] pp125 via booth.lse.ac.uk

[xxxi] Work among the fallen as seen in the prison cell : a paper read before the Ruri-Decanal Chapter of St. Margaret’s and St. John’s, Westminster, in the Jerusalem Chamber, on Thursday, July 17, 1890 by GP Merrick via archive.org

[xxxii] London, England, Poor Law School District Registers, 1852-1918 via ancestry.co.uk

[xxxiii] London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1924 Hammersmith and Fulham

St Andrew, West Kensington: St Andrew´s Road 1868-1893 via ancestry.co.uk

[xxxiv] London, England, Poor Law School District Registers, 1852-1918 via ancestry.co.uk

[xxxv] Charles Banfield Wackrill birth certificate in the author’s personal files

[xxxvi] Categorised as “2st” (or 2nd class) in the Booth notebooks referring to very poor people, typically living in crowded conditions, often unemployed or working very casual, unstable jobs.

[xxxvii] George H. Duckworth’s Notebook: Police District 28 [Kensington Town], District 29 [Fulham], District 30 [Hammersmith] Ref: BOOTH/B/361 pp 179 via booth.lse.ac.uk

[xxxviii] Ibid

[xxxix] Booth Poverty Map via https://booth.lse.ac.uk/

[xl] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; School Admission and Discharge Registers; Reference: LCC/EO/DIV01/HAL/AD/006 via ancestry.co.uk

[xli] 1891 England Census Class: RG12; Piece: 50; Folio: 97; Page: 56; GSU roll: 6095160 via ancestry.co.uk

[xlii] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: p74/jn/012 via ancestry.co.uk

[xliii] Fulham Chronicle 28 Oct 1892 via www.findmypast.co.uk

[xliv] London Metropolitan Archives; “London, England, UK”; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P77/Jn/003 via ancestry.co.uk

[xlv] Charles Edward John Banfield’s death certificate in the author’s personal files

[xlvi] Leah Banfield’s death certificate in the author’s personal files