⚠️ Content warning: The following story contains historical references to violence, including traditional headhunting practices, which some readers may find distressing.

I recently posted a series of images from my late father-in-law’s collection, taken in the Far East c.1945-46 while he was serving with the Royal Navy as a conscript during and after WW2. You can read the original piece and view some of his photos here.

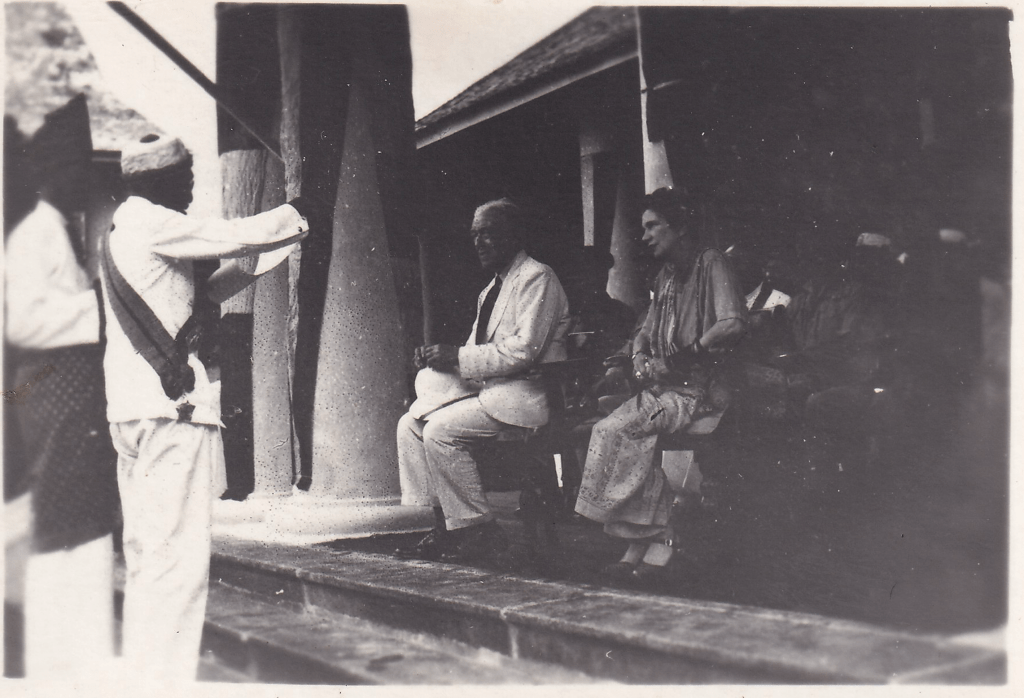

Amongst these tiny faded prints is a sequence showing a clearly important ceremonial event: the minesweeper HMS Pickle decked out with flags, her crew parading in immaculate tropical whites as a guard of honour, a colonial-era ceremony, and some scenic images. From pencilled notes on the back, I knew the location was Kuching in Sarawak (Borneo) and was intrigued. What was the occasion?

After some detective work, I discovered these photographs were taken in early May 1946, during a visit by two British Members of Parliament: David Reece-William, Labour MP for South Croydon, and David Gammans, Conservative MP for Hornsey. Both men spoke fluent Malay and had been sent by the British government to gauge opinion in Sarawak ahead of a major political shift that would change the territory’s fate.

Less than two months later, the Kingdom of Sarawak – an autonomous state ruled for more than a century by the Brooke family, was ceded to the British Crown.

David Reece-Williams, later recalled:

“We drove into Kuching and there moored to the jetty was H.M.S. Pickle put at our disposal by Lord Louis[1], spick, span and shining, with deck awnings up. A group of sailors in white shirts and shorts leant over the side and watched us as we drove up where the Captain, Commander C. P. F. Brown, D.S.O., was waiting to greet us. H.M.S. Pickle was a new thousand ton Flotilla leader minesweeper bearing the name of a predecessor which had borne the news of Lord Nelson’s death to England after the battle of Trafalgar.”[ii]

So there it was, my late father-in-law had retained a little collection of snapshots capturing this historic moment – a prelude to the end of the Brooke dynasty in Sarawak.

But what led to this moment? And what happened next?

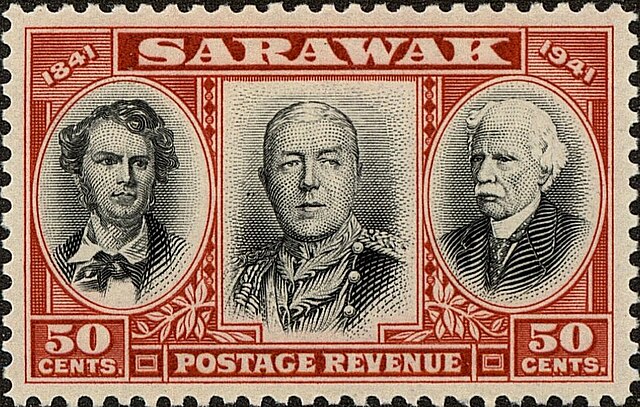

The Brooke dynasty

In 1833, while in Singapore, a young Englishman named James Brooke heard of a rebellion in Borneo about an area allegedly controlled by head-hunters and pirates destroying native trade and terrorising the local people. In his diary James wrote:

“God has made me to be the suppressor of head hunting and slavery in Sarawak”[iii].

He confidently declared to the Sultan of Brunei that he would put down the rebellion – in exchange for the territory of Sarawak. Both were gentlemen of their word. In 1840, armed with a cutlass, one muzzle-loading gun, and a small band of Englishmen and local boatmen, Brooke landed at Kuching and quelled the uprising. He was proclaimed the first White Rajah of Sarawak in 1841.[iv]

James had suffered an unfortunate injury as a young man which had left him unable to sire children, thus the title passed in 1868 to his nephew Charles Brooke, and then in 1917 to Charles’ eldest son Vyner Brooke, who became the third and final Rajah.

Although Britain signed a treaty in 1888 agreeing to protect Sarawak without interfering in its internal governance, it was increasingly clear by the 1930s that personal rule by a single white dynasty was becoming untenable.

Changing times

Under the Brookes, Sarawak largely avoided the worst excesses of colonial exploitation. Determined to protect the indigenous population from the encroachment of Western business interests, the White Rajahs maintained a paternalistic style of government that kept outside influences in check. But after the First World War, a global boom in rubber and oil began to draw Sarawak into the wider world economy. By the 1930s, the once-idyllic image of Brooke rule was beginning to fade. The concept of one-man rule appeared increasingly outdated, and there had been no serious attempt to define or develop native political rights. Although the Third Rajah believed that the Brooke dynasty had turned Sarawak from ‘a country of savagery and barbarism into one of prosperity’[vi], he tried to modernise and, in 1941 (the centenary of Brooke rule) he introduced a constitution aimed at eventual self-government.

However, a few short months later, the Japanese invaded. Europeans were interned, and Vyner escaped to Australia. From there, he transferred his authority to a Commission in London[vii].

In February 1945, a joint British/Australian guerrilla unit parachuted behind enemy lines into Sarawak’s highlands to support resistance against the Japanese. Working with the indigenous tribes, they trained and armed local fighters and, with the Brooke-era ban lifted, traditional headhunting practices resumed. Sarawak was formally liberated in September 1945 by Australia’s 9th Division.[viii]

A Kingdom for a Million Pounds

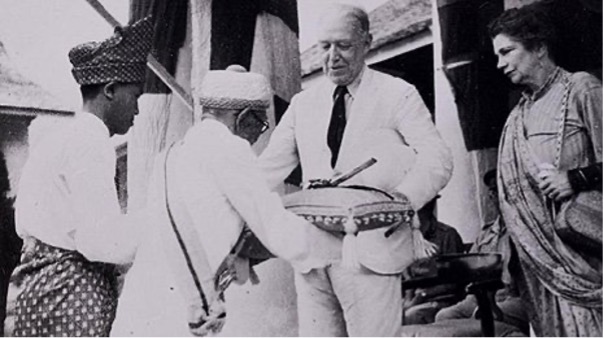

In 1946, with war over, Vyner and his wife Sylvia, the Ranee, returned from exile. They found Sarawak devastated and their dynasty in turmoil. Vyner had three daughters but no male heir, and a bitter family feud broke out over who would succeed him.

In an effort to resolve the situation, Vyner dispatched his private secretary, Gerard MacBryan, to consult with Sarawak’s native leaders. Word soon reached London that most were open to British rule – but allegations quickly surfaced that money had changed hands to secure their agreement.

Meanwhile, it became clear that Vyner and his family would receive substantial compensation – around £1 million, an immense sum at the time.[x]

In the light of this politically sensitive atmosphere, the British government decided to send two Malay-speaking Members of Parliament to Sarawak to gauge local sentiment on the proposed cession.

To the Edge of the World

After enduring long and arduous journeys by flying boat, the two representatives of the British establishment, Colonel David Reece-Williams and Captain David Gammans (the latter’s title being an honorary one from his colonial service – he was a lawyer, not a military man) – arrived in the sweltering heat and complex political climate of postwar Sarawak. Their visit, though relatively low-key, would prove highly significant.

On arrival in Kuching, they boarded HMS Pickle, a naval minesweeper recently scrubbed down in Singapore by Japanese prisoners of war in preparation for the MPs’ mission. The crew, no doubt grateful for a reprieve from mine-sweeping duties, now found themselves ceremonial hosts.[xi]

Despite the ship’s spring-clean, Gammans later described how he and Reece-Williams – both clearly used to more comfortable quarters – had to share a small cabin infested with rats and cockroaches.[xii] Nevertheless, they seemed reluctant to spend a night ashore, preferring to remain aboard whenever possible.[xiii]

Reece-Williams described Kuching as a modest town with Chinese shophouses and warehouses, Malay homes on stilts, and a scattering of European residences. There was a small cinema and a couple of nightclubs, but “rats, lean, hungry and agile were everywhere”.[xiv] On the opposite bank of the Sarawak River stood the long, low, whitewashed Astana palace, the White Fort, and police barracks – imposing reminders of the colonial and dynastic authority.

Although no doubt mindful of the hazards of underwater obstacles, sandbanks, and the ever-present hungry crocodiles, Commander Brown, captain of the Pickle, accommodated his passengers’ reluctance by taking the ship upriver as a far as he believed was safe. For inland visits, smaller launches and boats were arranged.[xv]

Ghosts of the Occupation

As HMS Pickle edged deeper upriver into the jungle interior, the river narrowed, and dense vegetation pressed in from both banks. In the thick, humid air, the juxtaposition of the British establishment figures aboard a refitted minesweeper slowly making their passage into a land still shaped by violence and spiritual beliefs must have been surreal and unsettling.

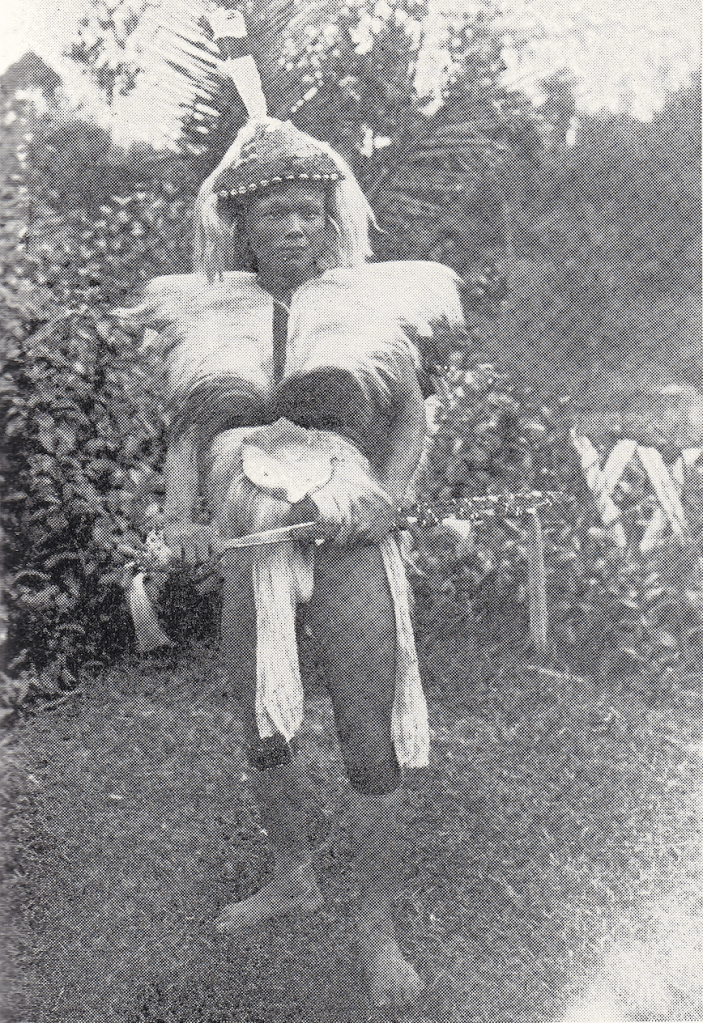

As the MPs travelled further upstream, they were confronted with grim reminders of the recent occupation. During the Japanese rule of Sarawak, the indigenous peoples – particularly the Iban (then often referred to as Dyaks), who made up nearly a third of the population – had mounted fierce resistance from the uplands. British and Australian commandos, including the eccentric but effective Tom Harrisson of the Z Special Unit, had parachuted behind enemy lines to support the guerilla effort. Harrisson (later Director of the Sarawak Museum[xvi]) trained and armed local tribespeople, many of whom welcomed the lifting of the Brooke-era ban on headhunting – a practice once central to their cultural beliefs around power, fertility, and prosperity.

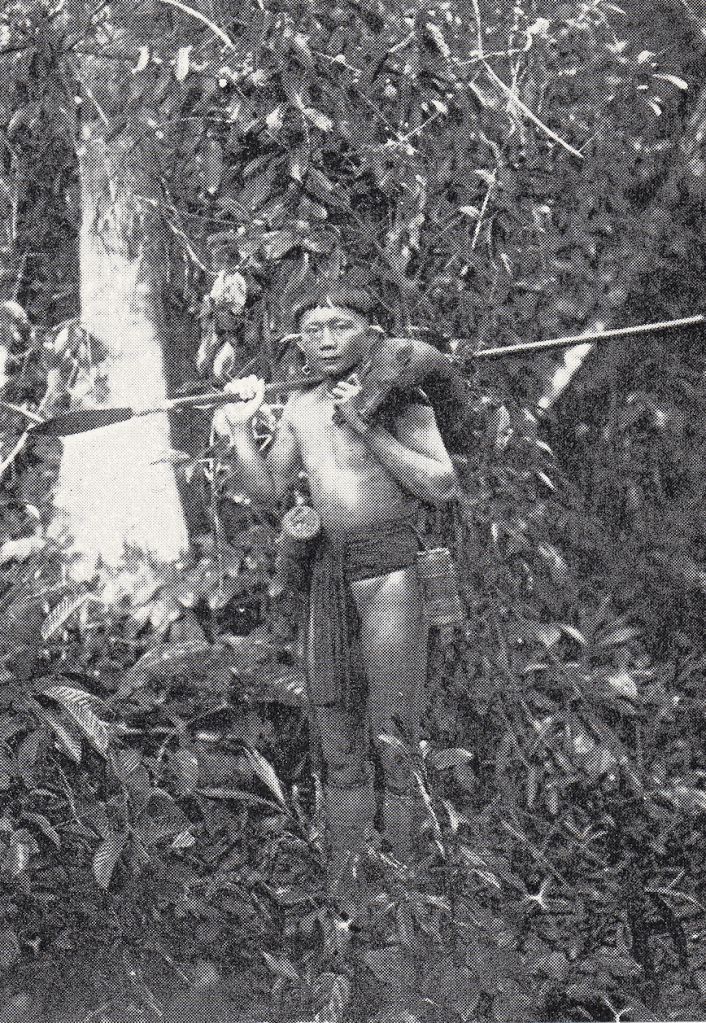

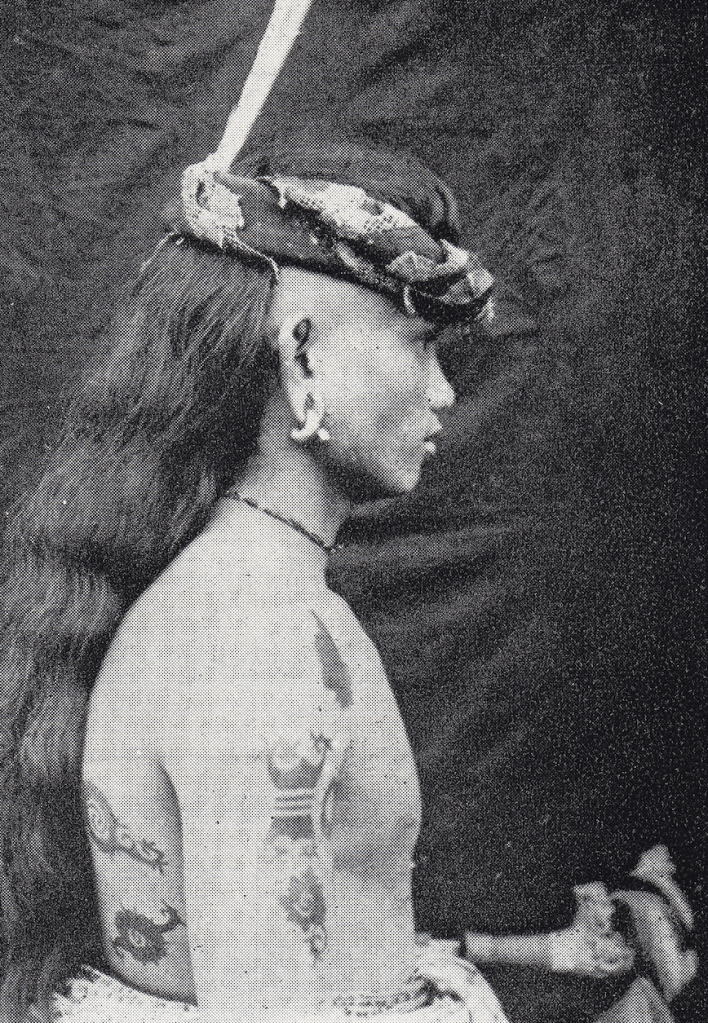

Iban tribespeople and a traditional longhouse (click on an image to enlarge)[xvii]

An estimated 1,500 Japanese heads were taken during the occupation.[xviii] Some bore gold teeth and spectacles – the latter polished regularly as a mark of respect – and were proudly displayed in longhouses, where their presence was believed to bring good fortune to the community.

Reece-Williams later wrote, “The Japanese, except in strong parties, were afraid to venture into Iban country. Often those that did so never came back.”[xix] One popular – if grisly – account described how young Iban women were sent by their elders to bathe in jungle pools to lure Japanese soldiers. As the unsuspecting onlookers crept in to watch, they were ambushed and decapitated.[xx]

By the time Reece-Williams and Gammans arrived in Sarawak, such stories were still fresh in the minds of the local population – and not without consequence for the visiting MPs. In one village, they were solemnly offered the preserved head of the former Japanese Director of Education – a particularly esteemed trophy. Only the most delicate diplomatic footwork saved the situation from descending into cultural misunderstanding and offence.[xxi]

Unfortunately, because the MPs’ refused to sleep ashore, they mainly interacted with towns so had limited contact with the people living inland. After a quick survey, Gammans and Rees-Williams concluded that people in Sarawak were generally supportive of the proposals[xxii]

Return to Kuching

With the mission now complete, HMS Pickle turned back downstream towards Kuching. During the journey, Reece-Williams later recalled overhearing two young sailors discussing the purpose of their visit. One remarked: “These politicians have come out here to pinch this country from the Rajah, from right under his nose poor old b…..”. That night, under a tropical moon, Reece-Williams and Gammans assembled a group of half-dressed sailors on deck for an impromptu seminar on the Sarawak question – along with a crash course in the more arcane workings of the British parliamentary system.[xxiii] Reece-Williams considered the session a great success, though history is silent on what the young ratings made of it.

After docking at Kuching, the MPs sent a cable back to London confirming that, as a result of their enquiries, they believed there was sufficient acquiescence – or at least a lack of serious opposition – to justify the question of cession going before the Council Negri, the State Council.[xxiii]

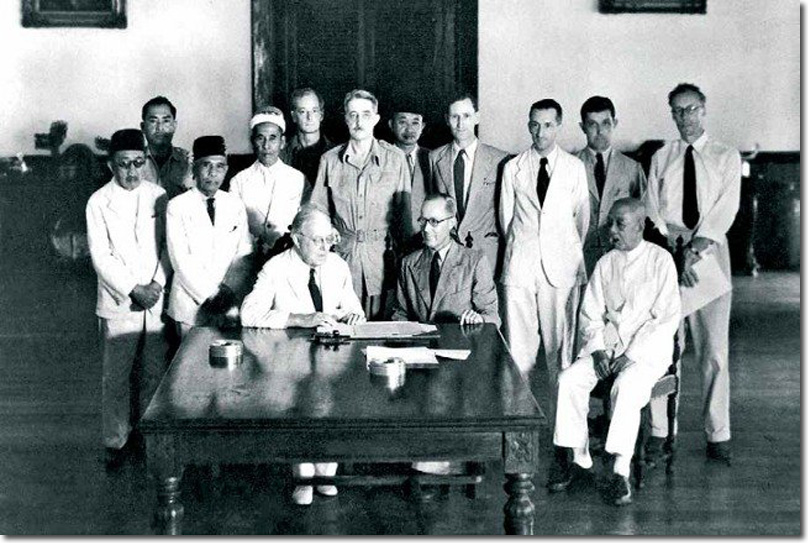

The stakes were high on 15th May 1946, as the Council Negri met for the Second Reading of the Sarawak Cession Bill. The rubber-stamp parliament, suddenly tasked with deciding the fate of the nation, was filled with emotions. Many of its members were political appointees of the Brooke regime, yet even among them, opinions were divided.

The vote was closer than London may have hoped – and far from the unqualified endorsement that Whitehall had expected. The Bill was carried by the narrowest of margins: 18 votes to 16. The following day, the Committee Stage and Third Reading were hurried through – despite protests, walkouts, and at least one abstention.[xxiv]

The Pickle, now with her passengers’ mission fulfilled, set off for a two-day cruise to Singapore. No doubt the officers and crew were greatly relieved to be leaving behind the uncharted waters of the Sarawak River to return to the navigational comforts of buoys, lighthouses, and beacons.

Aftermath

The Cession Agreement of Sarawak was formally signed just three days after the Council Negri vote. The speed of the transition has often since been cited as evidence of how swiftly the British moved to secure the transfer – despite considerable opposition among the local Malay population and several members of the Council.

The above photograph reinforces a central point: although the Council Negri technically included both European and indigenous members, the balance of power was far from equal. European officials dominate the frame in both number and bearing – a visual reminder that, despite the appearance of consensus, Sarawak’s fate was shaped in decidedly colonial terms.

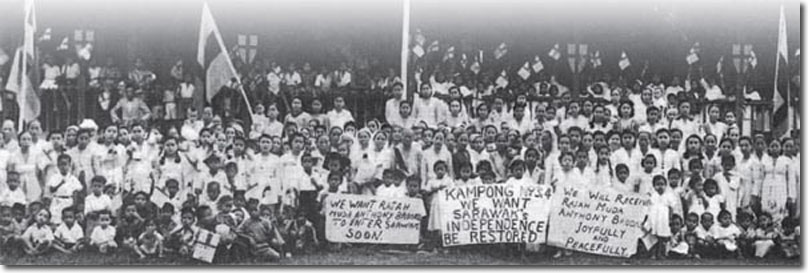

However, what the image does not convey – but what history records – is the growing resistance that followed. Many Sarawakians, especially Malays, felt they had been sold out. Protests erupted. In 1949, the newly appointed British Governor, Duncan Stewart, was assassinated by anti-cession activists.

Ultimately, the cession of Sarawak marked the final territorial acquisition of the British Empire. Yet far from being a crowning achievement, it was born in controversy and ended in violence. Over time, the anti-cession movement faded, but resentment lingered. In 1963, Sarawak joined the Federation of Malaysia, entering a new chapter as part of an independent nation, although debates over autonomy and identity have never entirely disappeared.

For the young Peter Poulton, a 20-year-old rating aboard HMS Pickle, the expedition must have left a lasting impression. He kept a few faded snapshots from the historic journey, but according to his family, never spoke of his time in Sarawak. It’s been a real privilege for me to research the background to these images and to try to tell the story behind them.

Click here for more images of Peter’s travels in Sarawak and the Far East between 1945 and 1946.

[1] Lord Louis Mountbatten, then Supreme Allied Commander, Southeast Asia Command, later 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma

[i] From the author’s personal collection

[ii] Contemporary Review, Vol-206, Jan-Jun 1965 ‘A Voyage in HMS Pickle’ by Lord Ogmore via archive.org last visited 20 May 2025

[iii] Queen of the Head-Hunters by H.H the Hon. Sylvia Lady Brooke published by Sidgwick & Jackson 1970

[iv] Ibid

[v] image in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons

[vi] Queen of the Head-Hunters by H.H the Hon. Sylvia Lady Brooke published by Sidgwick & Jackson 1970

[vii] Contemporary Review, Vol-206, Jan-Jun 1965 ‘A Voyage in HMS Pickle’ by Lord Ogmore via archive.org last visited 20 May 2025

[viii] https://www.brooketrust.org/history-of-sarawak last visited 02 Jun 2025

[ix] Image assumed to be in the Public Domain via https://www.brooketrust.org/history-of-sarawak last visited 02 Jun 2025

[x] Contemporary Review, Vol-206, Jan-Jun 1965 ‘A Voyage in HMS Pickle’ by Lord Ogmore via archive.org last visited 20 May 2025

[xi] Ibid

[xii] Sylvia: Queen of the Headhunters: an eccentric Englishwoman and her lost kingdom by Philip Eade published by Picador, New York, 2014 via archive.org last visited 03 Jun 2025

[xiii] Ibid

[xiv] Contemporary Review, Vol-206, Jan-Jun 1965 ‘A Voyage in HMS Pickle’ by Lord Ogmore via archive.org last visited 20 May 2025

[xv] Ibid

[xvi] Ibid

[xvii] Queen of the Head-Hunters by H.H the Hon. Sylvia Lady Brooke published by Sidgwick & Jackson 1970

[xviii] Ibid

[xix] Contemporary Review, Vol-206, Jan-Jun 1965 ‘A Voyage in HMS Pickle’ by Lord Ogmore via archive.org last visited 20 May 2025

[xx] Queen of the Head-Hunters by H.H the Hon. Sylvia Lady Brooke published by Sidgwick & Jackson 1970

[xxi] Contemporary Review, Vol-206, Jan-Jun 1965 ‘A Voyage in HMS Pickle’ by Lord Ogmore via archive.org last visited 20 May 2025

[xxii] Dictionary of Welsh Biography > WILLIAMS, DAVID REES (later REES-WILLIAMS, DAVID REES), 1st BARON OGMORE (1903-1976), politician and lawyer via https://biography.wales last accessed 04 Jun 2025

[xxiii] Contemporary Review, Vol-206, Jan-Jun 1965 ‘A Voyage in HMS Pickle’ by Lord Ogmore via archive.org last visited 20 May 2025

[xxiv] Ibid

[xxv] Image assumed to be in the Public Domain via the Sarawak Government website https://www.sarawak.gov last accessed 04 Jun 2025

[xxvi] Image assumed to be in the Public Domain via https://www.britishempire.co.uk last accessed 4 Jun 2025