When Victory in Europe was declared on 8th May 1945, my father-in-law Peter Poulton was thousands of miles away serving in the Royal Navy in the Far East. While people across Britain were dancing in the street, Peter and thousands of others were still deployed – or held as prisoners of war – facing uncertainty, tropical heat, and a continuing war against Japan. These three letters – from Peter’s mother, uncle, and father – arrived in the days immediately after VE Day. Their words offer us a glimpse into life at home: the joy, the weariness, the drink-fuelled relief, and the ever-present thoughts of a loved one still abroad.

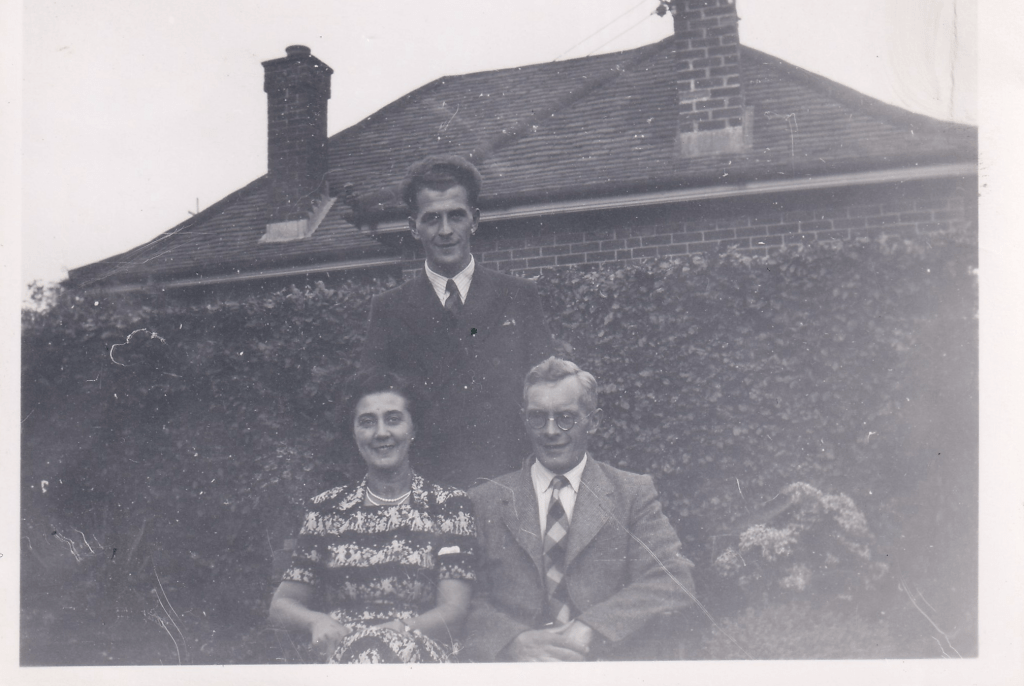

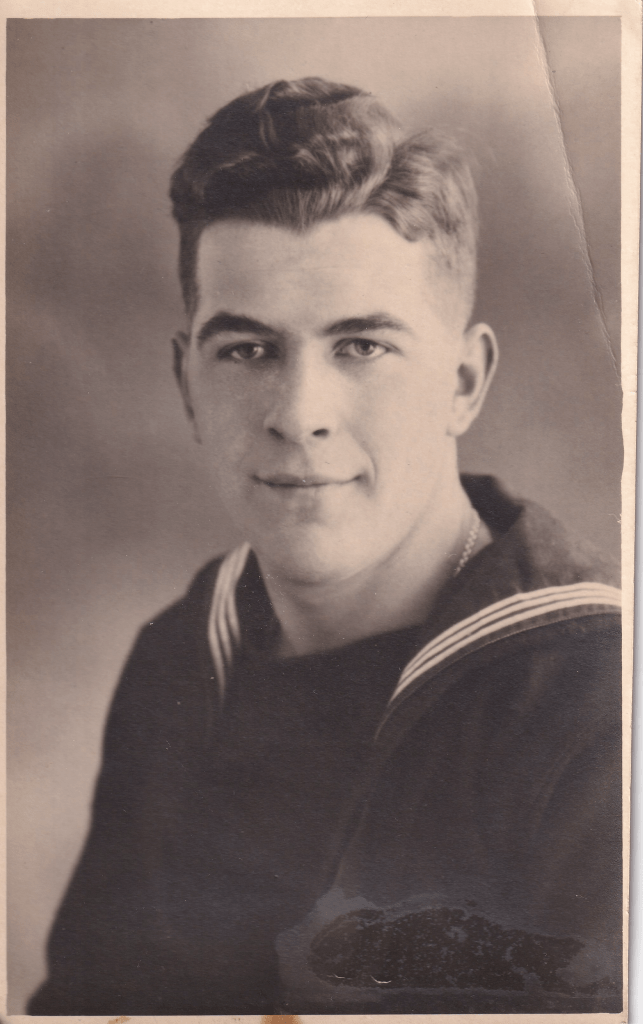

Peter was born in October 1925, and was the only child of Evelyn (‘Ciss’, née Hill) and Stanley Poulton. When these letters were written, Peter was a 20-year-old Able Seaman on active service at sea aboard HMS Pickle (J293), a Royal Navy minesweeper based in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

Written between the 9th and 12th of May 1945, the letters reveal how his family in Hungerford and Plymouth marked the end of the war in Europe, even as they kept him and others in the Far East constantly in mind.

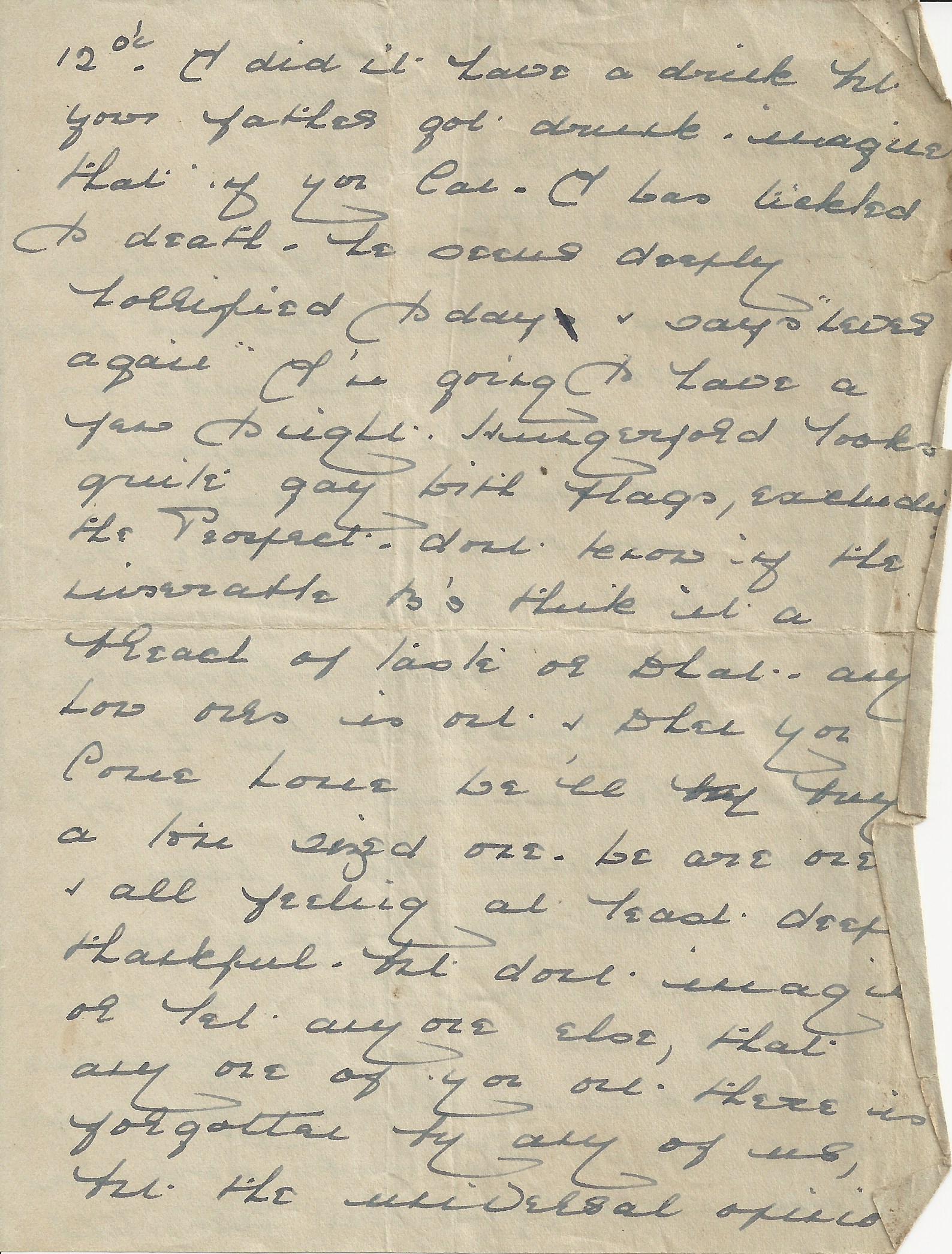

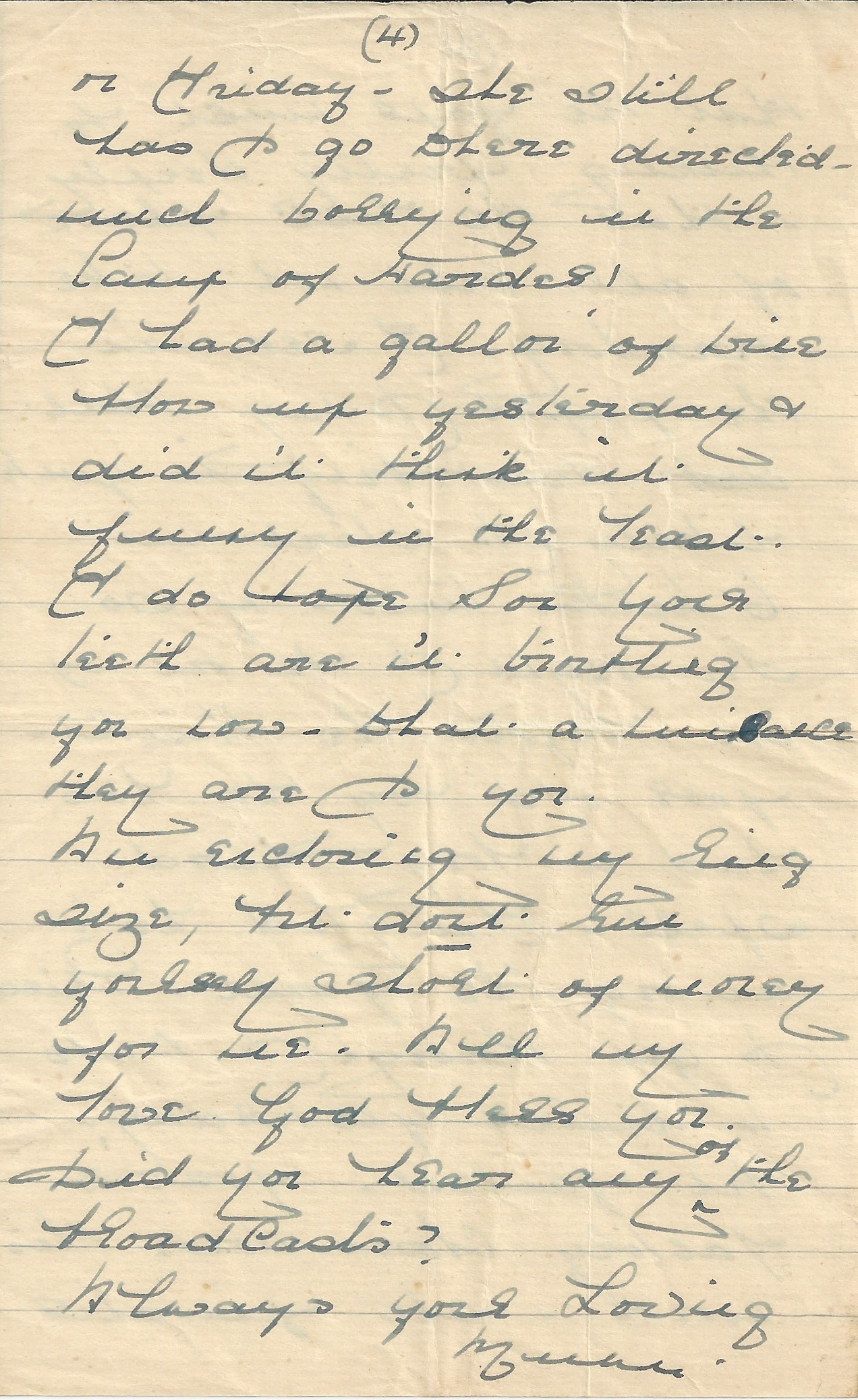

Peter’s mother was the first to write, on 9th May, the day after VE Day. She describes how they have had no postal service for over a week, but her words resonate with a combination of maternal affection and a dry wit. Despite the national relief, her comments reveal a feeling that wartime had lasted thirty years, not six, so the celebrations must have been even more impactful. However, she seems a little put out that their row of houses, ‘the Prospect’, was not decorated with flags – unlike most of the rest of the town of Hungerford – and she takes some delight in her husband’s clearly uncharacteristic drunkenness! “The pubs were open last night ( Yea – each late) till 12 o’c. I did not have a drink but your father got drunk – imagine that if you can. I was tickled to death – he seems deeply horrified today and says “never again”. I’m going to have a jar tonight.”

She emphasises that her son and others in the Far East are not forgotten and there is a general belief that Japan is likely reconsidering its position and hope that the war’s final phase won’t last much longer: “We are one & all feeling at least deeply thankful – but dont imagine or let anyone else, that any one of you out there is forgotten by any of us, but the universal opinion that the Japs must be thinking pretty deeply and that the last phase of all will not take overlong. “

Click here to view a transcript (link opens in new tab)

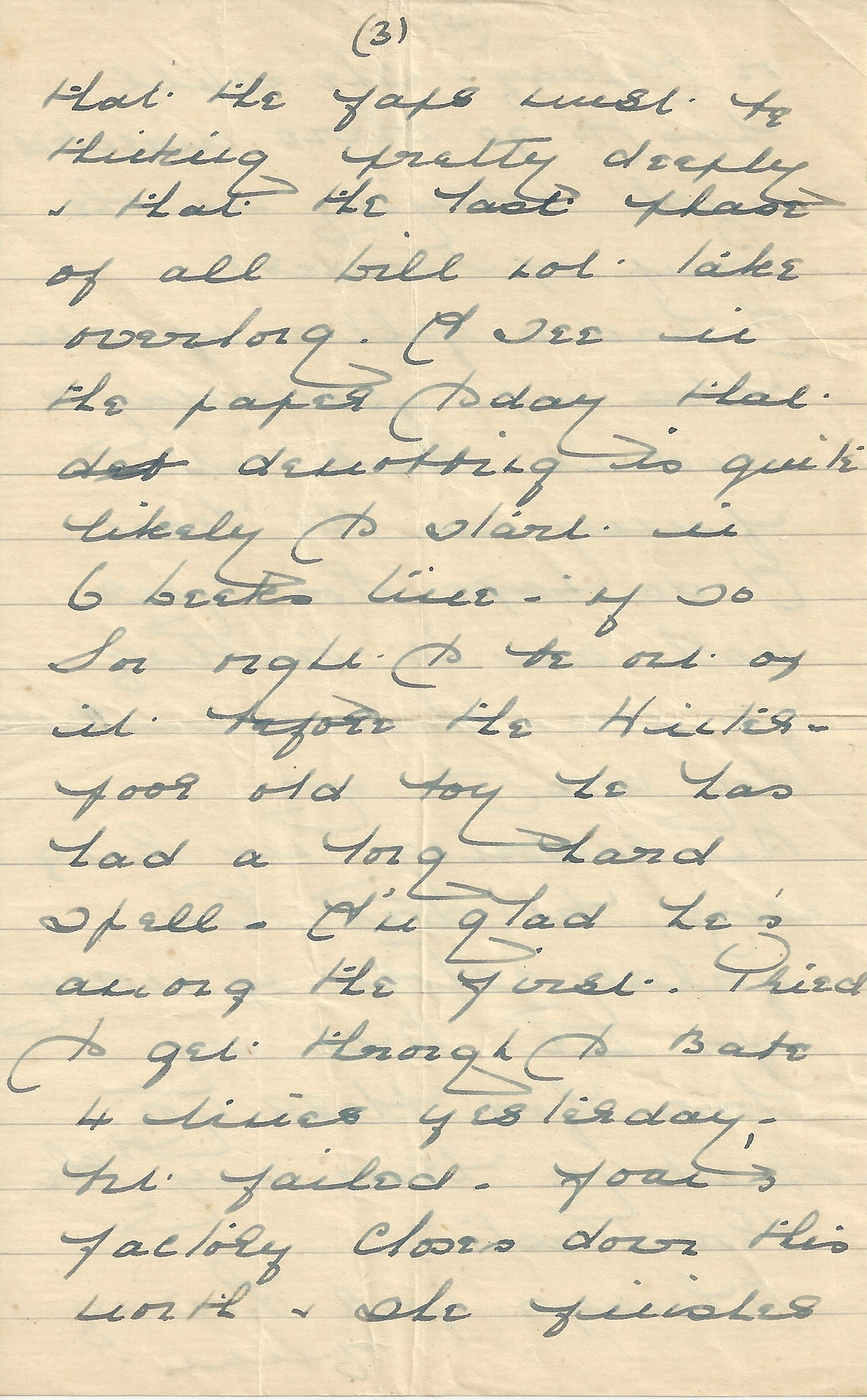

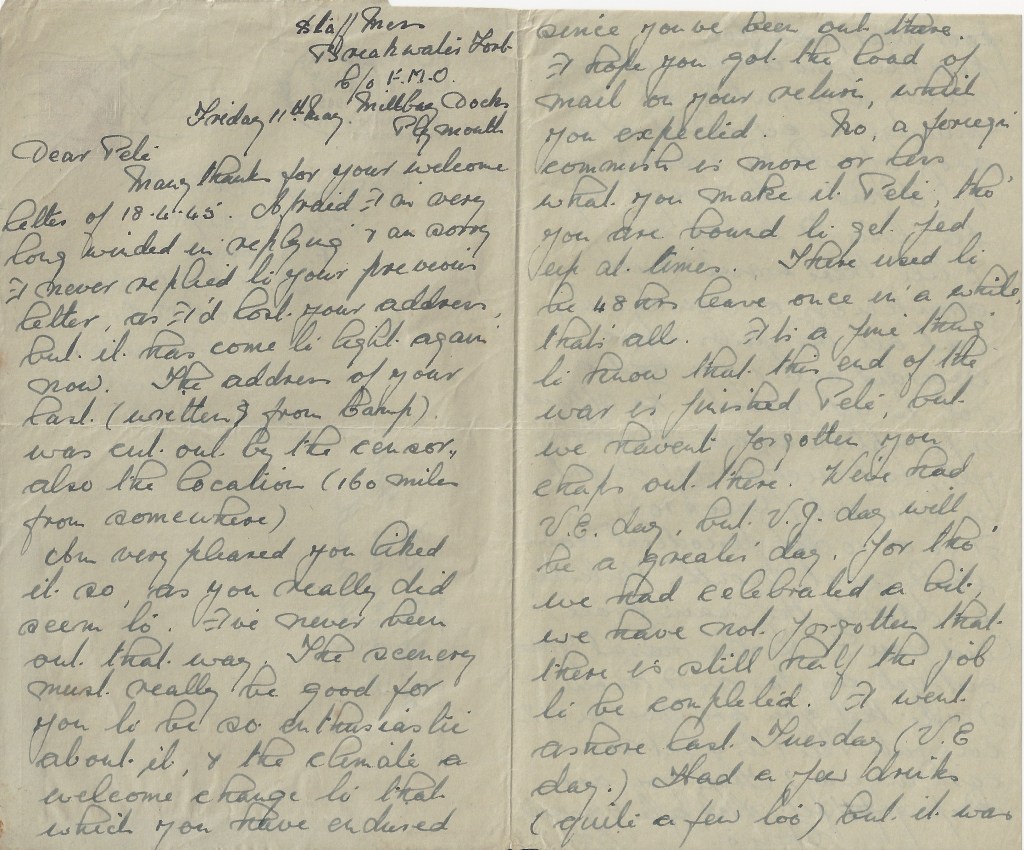

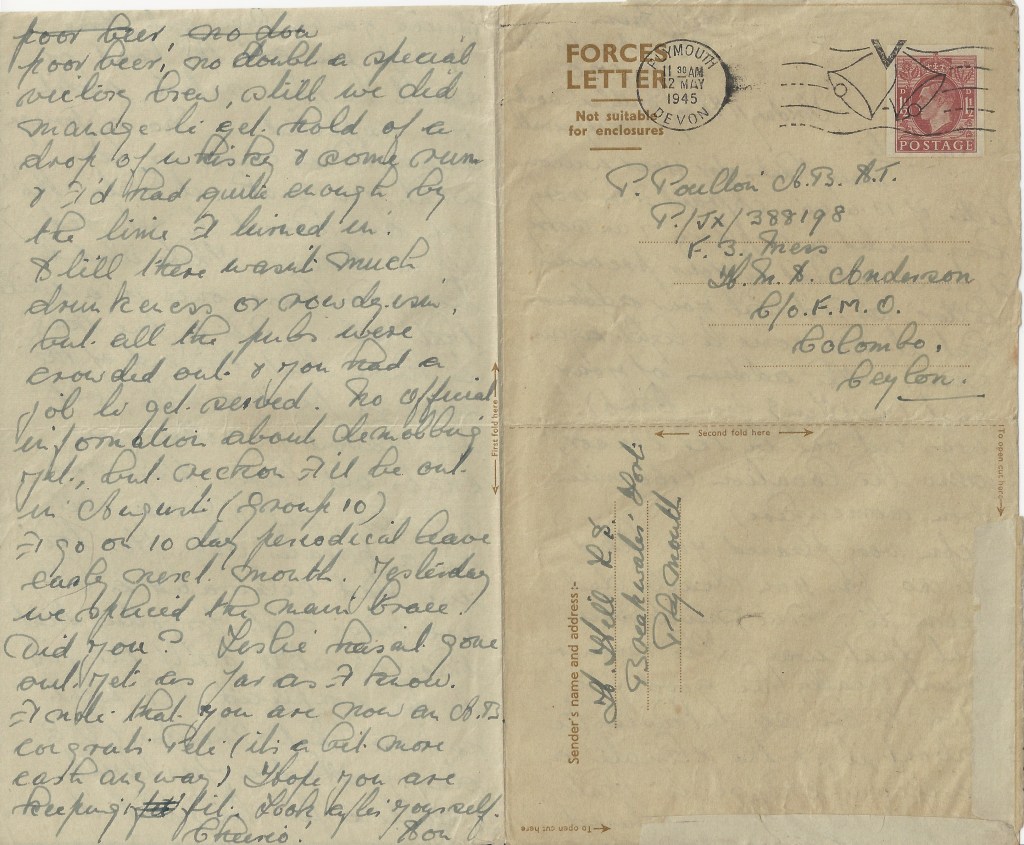

Two days later, Peter’s uncle (known as ‘Son’) also in the Navy writes from his base in Plymouth. He understands Peter’s life and conditions and offers advice on coping with an overseas posting: “No, a foreign commission is more or less what you make it, Peter, though you are bound to get fed up at times. There used to be 48hrs leave once in a while, that’s all.” He wants Peter to know that, despite the war in Europe being over, those still serving in the Far East are not forgotten: “It’s a fine thing to know that this end of the war is finished, Pete, but we haven’t forgotten you chaps out there. We’ve had VE Day, but VJ Day will be a greater day. For though we have celebrated a bit, we have not forgotten that there is still half of the job to be completed.“

He describes his own experience of the celebration in a low-key – almost understated – way: “I went ashore last Tuesday (VE Day). Had a few drinks (quite a few too) but it was poor beer, no doubt a special victory brew. Still, we did manage to get hold of a drop of whisky and some rum and I’d had quite enough by the time I turned in.

Still there wasn’t much drunkenness or rowdyism, but all the pubs were crowded out and you had a job to get served.”

Click here to view a transcript (link opens in new tab)

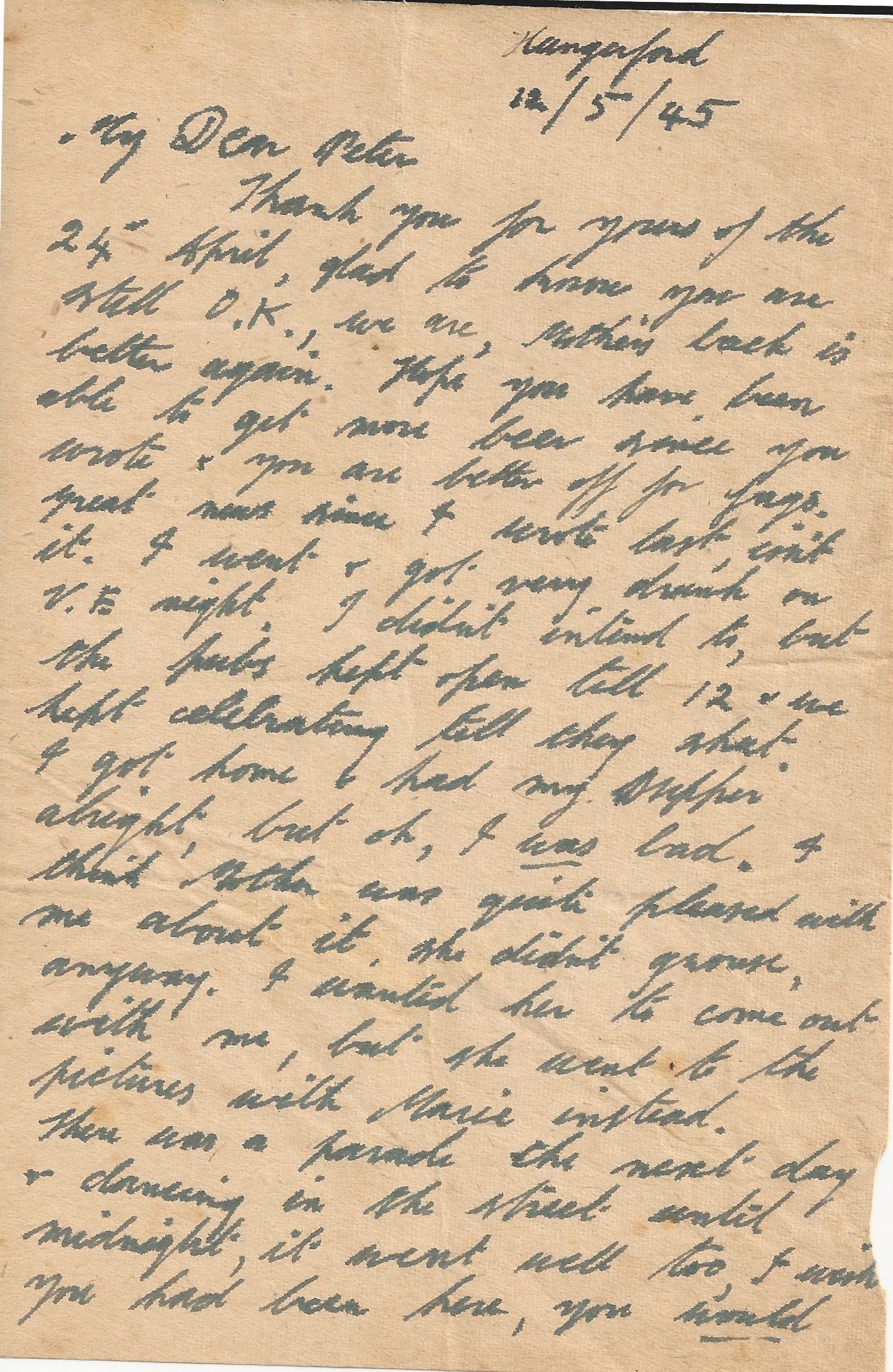

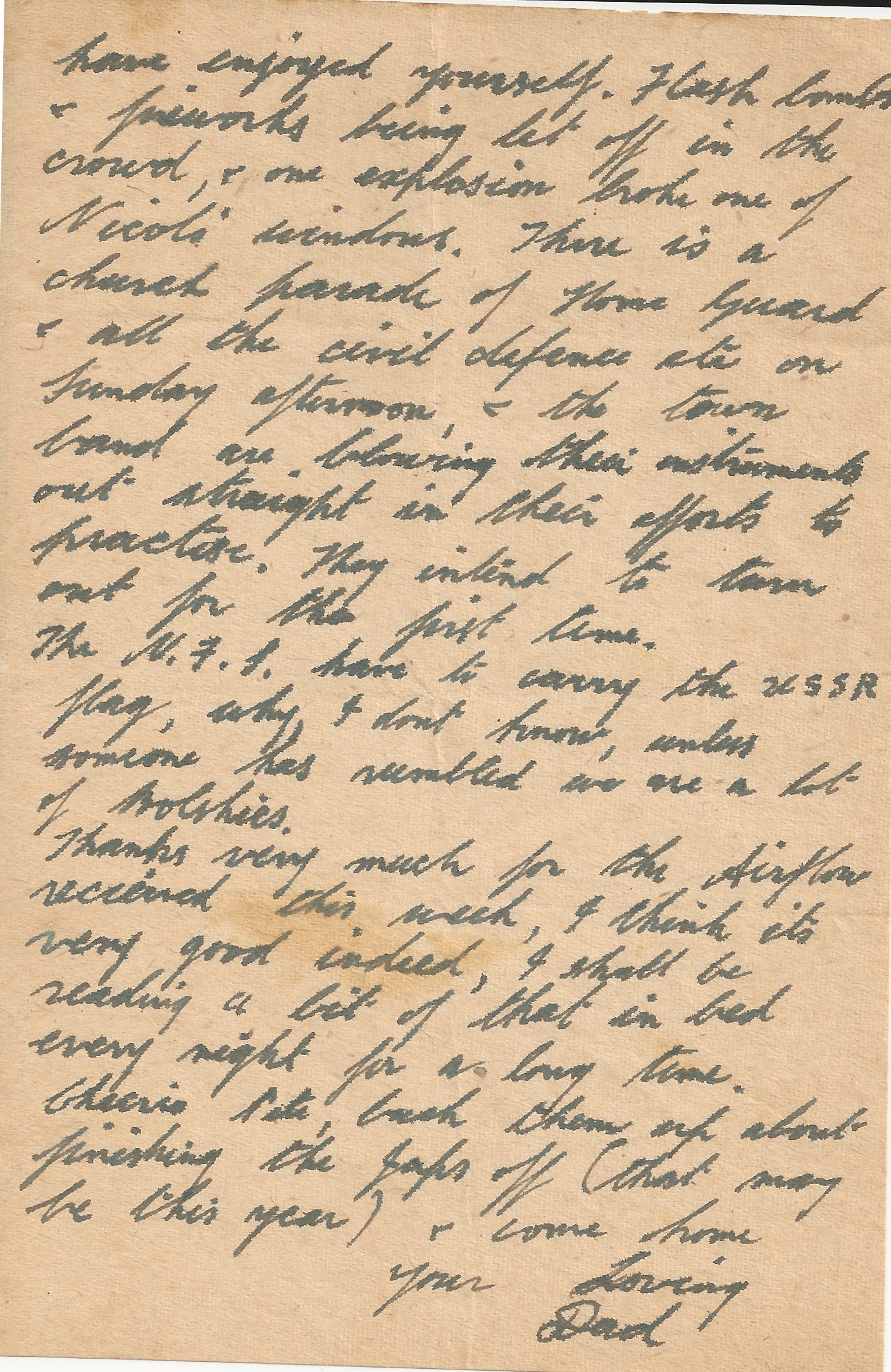

The third and final letter is from Peter’s father, Stanley, who shamefacedly admits to getting very drunk on VE night: “I didn’t intend to, but the pubs kept open till 12 and we kept celebrating till they shut. I got home and had my supper alright, but oh I was bad. I think Mother was quite pleased with me about it. She didn’t grouse, anyway. I wanted her to come out with me, but she went to the pictures with Marie instead.”

This is a wonderful letter where he paints a picture of spontaneous celebration – a mixture of joy and chaos with flash bombs and fireworks being let off in the streets resulting in a shop window being smashed – however the underlying sentiment is how he longs for Peter to be home to share it: “There was a parade the next day & dancing in the street until midnight, it went well too, I wish you had been here, you would have enjoyed yourself.”

Click here to view a transcript (link opens in new tab)

What stands out most in these WW2 era letters is how everyone – whether at home or in uniform – was trying to mark the end of one chapter while acknowledging that another remained open and unresolved. The joy was real, but so was the waiting. While people on the streets of Hungerford and Plymouth danced and drank themselves silly, they never stopped thinking about Peter, and others like him still serving far away.

These family letters are deeply personal, yet they echo a shared story of longing, courage, and connection. For Peter, they must have brought comfort – a reminder of home and of being remembered, at a time when those serving in the Far East could easily feel overlooked in the wake of VE Day. For us, reading them eighty years on, they open a window onto a world where love, humour, and hope endured, even in the shadow of war and amidst the uncertainty of what lay ahead.