Names should be simple. They anchor us to our past, connecting us to family, to a place, and to our history; but for Julia Fitzgerald, née… well, that depended on who was listening.

Believed to have been born around 1840 in County Cork, she might have first been Lane. Or Lahan. Or Leahan.

Who was Julia, and what can we really know about her?

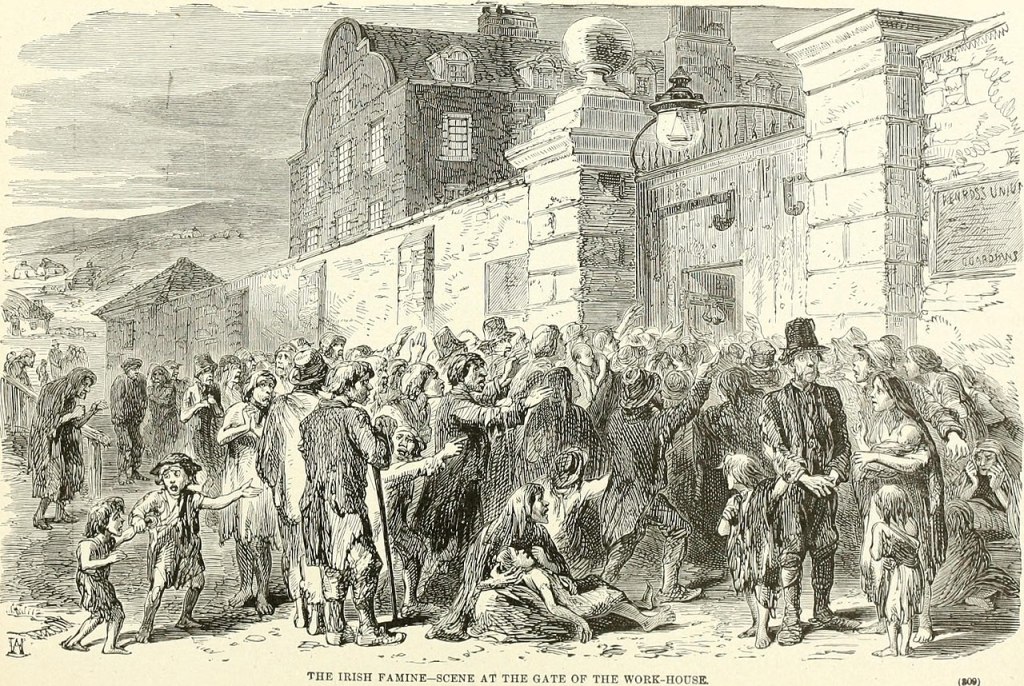

She grew up during the Great Famine, when the failure of the potato crop caused by blight led to widespread famine in Ireland. Modern estimates suggest that the famine led to the deaths of between one and one-and-a-half million people. It also triggered a wave of mass emigration.

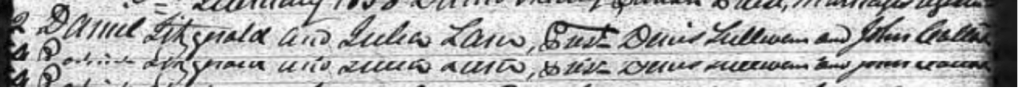

Aged about eighteen, Julia married Daniel Fitzgerald, a young man from Liscarroll — a parish adjacent to her likely birthplace of Kanturk — on 2nd February 1858. The handwritten record shows her as Julia Lain.

Daniel and Julia’s eldest son Edward was born in Liscarroll, and baptised on 24th June 1860. On that occasion, Julia’s name appears as July Leane.

Their second child, Margaret, was also born in Ireland around 1863, probably Liscarroll, but her baptism has not yet been found.

Liscarroll was a mostly rural parish in a hilly part of County Cork. The village of the same name is today dominated by the vast ruins of Liscarroll Castle. Dating from the 13th century and now the third largest castle in Ireland, it was acquired by the English lord Sir Philip Perceval in 1625 as repayment of a debt – part of the broader colonial policy of land confiscation, that saw huge tracts of Irish land transferred from native Gaelic lords to English settlers. In the mid-17th century, the castle became a strategically important stronghold, but it was severely damaged by Cromwellian cannon fire and fell into ruin.

Despite this, the estate remained in the hands of the Perceval family for over 250 years. Their descendants, the Earls of Egmont, controlled thousands of acres of the surrounding land, including the fields and cottages worked by tenant farmers like Julia and Daniel’s families. Life here was precarious, shaped not only by the land but by those who owned it.

Liscarroll, like much of rural Ireland, suffered terribly during the Great Famine of the 1840s. Although County Cork was known for its fertile soil, the region was heavily reliant on the potato, and when the blight struck, devastation followed. Entire families were evicted for failing to pay rent. Workhouses overflowed. Starvation and disease claimed thousands. Even for those who survived, the years that followed were marked by deep poverty, population decline, and the ever-present fear of future hardship.

By the time Julia and Daniel married in Liscarroll in 1858, the worst of the famine had passed, but the scars were everywhere. Families had been torn apart. The rural economy was shattered. Emigration was no longer a desperate escape — it had become a common life plan.

Then, in 1863, another shift occurred. After the death of the local land agent, Sir Edward Tierney, the Perceval estates — long managed locally — were challenged in court by George Perceval, the 6th Earl of Egmont, who had inherited the title but not the accompanying fortune. After a successful legal battle, he regained control of the lands, ending the Tierney family’s influence[iii].

For tenant families like the Fitzgeralds, this legal turmoil may have meant new uncertainty — new rent demands, changes in tenancy, or even evictions. With few rights and no real security, many rural families weighed the risks of staying against the possibilities abroad. Sometime between 1864 and 1866, Daniel and Julia left Liscarroll behind, joining the tide of Irish emigrants seeking a foothold in London.

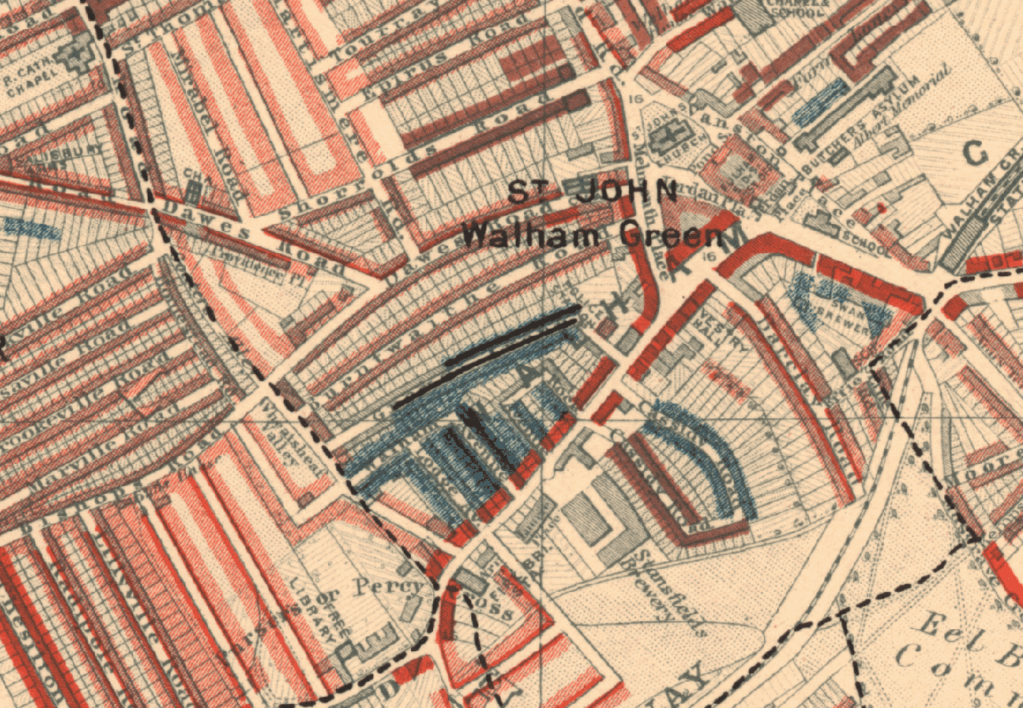

They likely left Ireland alongside other families from their local area — principally poor and unskilled labourers. On arrival in London, these emigrants became concentrated in certain districts, including Hammersmith and Fulham, where they lived in overcrowded and often unsanitary conditions. Many found work in casual, seasonal jobs in the market gardens that lined the western edges of the city.

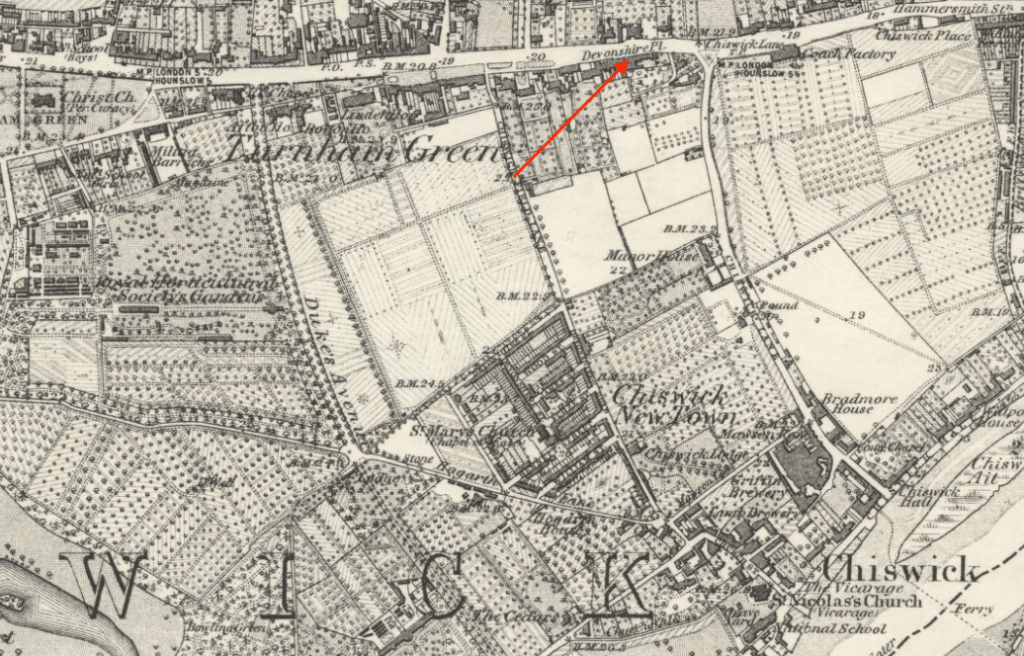

Daniel, Julia, and their two children initially settled in Devonshire Place, Turnham Green, near Chiswick in west London. At the time, Turnham Green was still a tiny hamlet surrounded by market gardens and open country owned by the Duke of Devonshire. The arrival of the railway in 1849 had created new opportunities, and the area’s population grew exponentially during the 19th century[iv]. The 1861 census[v] indicates that the residents of Devonshire Place were mostly English manual workers and their families, most of whom had come from outside the local area.

It’s likely that Daniel initially found work in one of the many market gardens surrounding Turnham Green — perhaps even at the nearby Royal Horticultural Society gardens, which covered a large area to the west of Dukes Avenue. Of the thirty-three acres, half were dedicated to fruit and vegetables; thirteen to flowers and shrubs, and eight formed an arboretum. Hot houses were constructed to house exotic plants arriving from the Far East, the Americas, and beyond, and the Society held lectures and ran training schemes for aspiring gardeners.[viii]

The neighbouring market gardens would have grown a wide variety of produce – quite different from the more limited crops of their native Liscarroll. For Daniel and Julia, the structured and cultivated landscape of west London must have been a striking contrast to the rugged, often harsh, farmlands of rural County Cork.

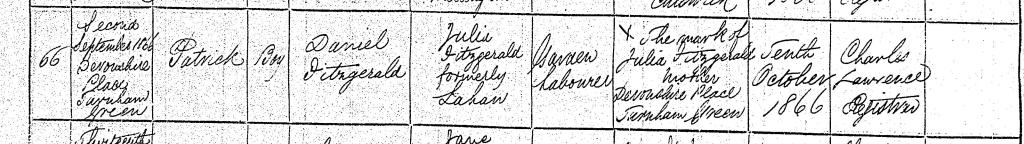

It was here, at Devonshire Place, Turnham Green, that Julia and Daniel’s third child, a boy they named Patrick, was born on 2nd September 1866. Daniel was then working as a garden labourer, and Julia — who registered the birth — was recorded as Julia Fitzgerald, formerly Lahan[ix].

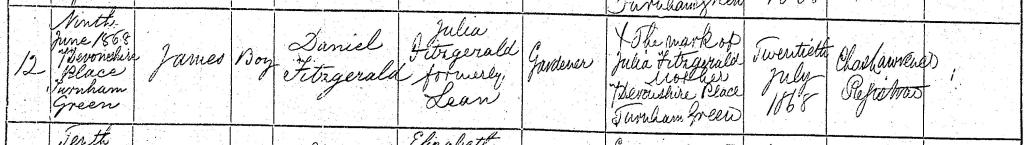

Less than two years later, on 9th June 1868, another son, James, was born at the same address. This time, Daniel’s occupation was listed as “gardener”, suggesting some advancement, and Julia, who again registered the birth, was this time recorded as Julia Fitzgerald, formerly Lean[x].

However, Daniel’s aspirations clearly stretched beyond horticulture. Later that same year, in 1868, he was accepted into the Metropolitan Police,[xi] and joined with ‘T’ division based in Chelsea[xii] as a police constable with warrant number 51079.

This was a rare and respectable position for an Irish immigrant in London. The job brought a steady income and a measure of status — not easily obtained. By regulation, every recruit had to be at least five feet seven inches tall, of strong constitution, able to read and write, and – crucially – be of “unimpeachable character for honesty, industry, sobriety, and good temper” [xiii]. Competition was fierce: in 1869, over 4,500 men applied to join the Metropolitan Police, but fewer than one in four made it through the rigorous selection process[xiv].

No doubt Julia was so very proud to see her husband standing tall in his dark blue, high-collared tunic with metal buttons and collar numerals; a leather belt suspending his truncheon case; a knee-length greatcoat; heavy boots; and the distinctive cork helmet covered in fabric and bearing the divisional letter and number on a shining metal plate[xv].

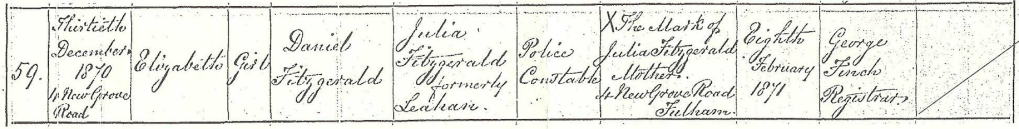

It was around this time, the Fitzgeralds moved south across the Thames to Fulham, where their second daughter, Elizabeth, was born at New Grove Road on 30th December 1870 during the coldest winter in living memory[xvi]. One police officer noted in his diary: “From the 25th Dec 1870 to 1st January 1871 there were 13 deaths in London through the effects of the cold and hard frosts. Some of the lakes would bear horses and sledges. Sunday night January 1st 1871 was the coldest night ever known”.[xvii] This tiny baby, born in such bitter conditions, would one day become my great-grandmother.

Unsurprisingly, it wasn’t until February that Julia braved the icy streets of Fulham to register Elizabeth’s birth. This time, Julia’s name was recorded by the registrar, George Finch, as formerly Leahan.

By now Julia’s name had become a puzzle of ink-stained guesses — Lain, Lahan, Lane, Leahan, Lean, Leane, Leehan – the combination of letters shifting with each official record as different clerks listened and tried to interpret her Irish accent. Unable to read the words placed before her, Julia likely nodded politely and accepted whatever version was written down. Then, as ever, she marked each official document with an ‘X’.

By the time of the 1871 census, the Fitzgeralds were living at No. 4 New Grove Road, Fulham. The household included Daniel Fitzgerald, aged 32, recorded as a labourer; his wife Julia, aged 30; and their children: Edward (10) and Margaret (8), both born in Ireland; Patrick (3) and James (2), born in Chiswick; and baby Elizabeth, just three months old, born in Fulham. Curiously, although Daniel had joined the Metropolitan Police in 1868 and was still serving as a constable, the census lists his occupation simply as “labourer”. [xviii] This may have been an error by the enumerator — who completed the form on the family’s behalf and may have assumed a manual-labour role based on their Irish neighbours – or it may reflect Daniel’s own understatement—or Julia’s, if he was out on the beat when the enumerator called—perhaps to avoid drawing undue attention.

By 1873, the family had moved again — this time to Victoria Road in Sands End, Fulham, formerly the site of a vast market garden which at the time was described as having being planted “with an immense number of pear, apple, walnut, and mulberry trees, and gooseberry, currant and raspberry bushes”[xix], where a collection of new, mostly 2-up-2-down, terraced cottages were laid out to house the hundreds of workers employed in the gas works and riverside industries and their families.

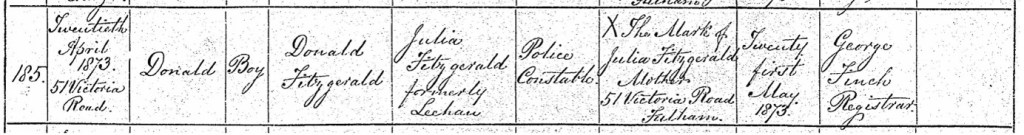

Then, on 20th April that year, Julia gave birth to another son. He was to have been named after his father, but once again her illiteracy let her down. When Julia gave the name to the registrar, it was misheard and entered as “Donald.” In fact, the father’s name was also mistakenly recorded as “Donald” Fitzgerald, a Police Constable. Still, the registrar was at least consistent — Julia was once again recorded as formerly Leehan.

Minor errors in Victorian civil‐registration entries were surprisingly common and usually did not cause long‑term legal trouble so long as the child was consistently known by the intended name in the community and on subsequent records. Parents who spotted an error could, within a few weeks, return to the local superintendent registrar with the original certificate and request a marginal correction. Perhaps Julia, unaware of the mistakes, simply folded the certificate neatly away and tucked it into a box with the other documents she knew were important, even if unintelligible.

Some ten years after Daniel and Julia left Ireland, life was looking promising. They had a home, Daniel had a steady job, and their six children were growing up fast. But life can be very cruel. In the summer of 1879 Daniel developed appendicitis (or ‘perityphlitis’, as it was called back then) and would have experienced pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. At that time, before antibiotics, mortality rates for the condition were over 75%[xx]. Daniel was not one of the lucky ones, and the infection developed into peritonitis. Despite being seen by a doctor, he died at home at 5 Victoria Road on 20th July, aged just forty-three[xxi].

Perhaps because of Julia’s illiteracy, the death was registered the next day by their eighteen-year-old son Edward, who was with his father when he died.

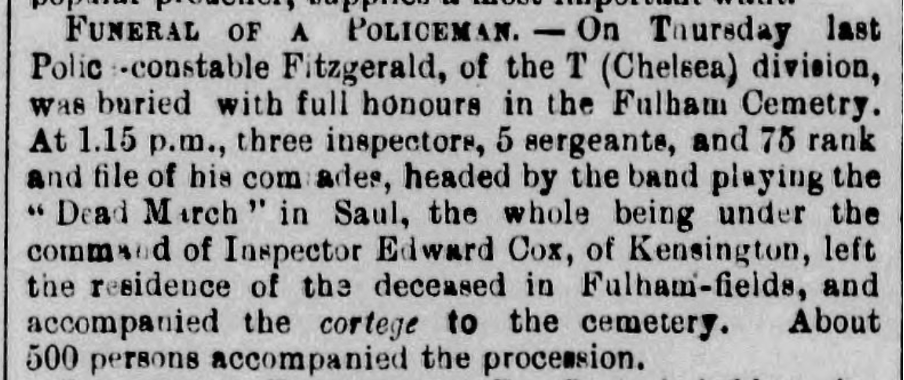

Daniel must have been well-respected as he was given a police funeral with full honours, attended by more than eighty colleagues, including five sergeants and three inspectors and a full band. Around five hundred mourners accompanied the sombre procession to his interment at Fulham Cemetery.

Unfortunately, for Julia and the children, there was no entitlement to a widow’s or children’s pensions following a death in service, except at the discretion of the force and only when an officer had been killed in the execution of duty. A formal support system for families was not established until the Police Act of 1890[xxiii].

Despite her heartbreak, Julia was resourceful and resilient, and the family quietly pulled together. The 1881 census[xxiv] finds them at No. 1 Victoria Road, crammed into a tiny two-up-two down cottage with a family from Flore, in Northamptonshire: Thomas and Jane Blunt, both gasworks labourers, and their daughter Betsy aged one year. Perhaps Julia was looking after little Betsy so her parents could work their shifts. Of Julia’s children, Edward (20) is a letter carrier (postman), Patrick (14) and James (12) are both errand boys, Elizabeth (10) and Daniel (7) are both at school, and they have a 23-year-old lodger, Daniel O’Hara, a police constable from Ireland. Her elder daughter Margaret, who would have been about 18, is no longer listed and may be working in service somewhere else. No. 5 Victoria Road, where the Fitzgeralds had lived for some years, and the place of Daniel’s death, was now uninhabited.

However, the demographic of Sands End was rapidly changing with an influx of poorer and unskilled workers hoping for employment in the nearby gas works and other industries. By 1889, a social survey described the area as a “Poor criminal patch between Bagleys Lane & Wandsworth Bridge Road”, and Victoria Road as “Irish, noisy, poor, a few criminals and licence holders”[xxv].

Sometime in the next four years, Julia and her family moved from Victoria Road to two rented rooms in Walham Avenue, about half a mile away. She was likely staying just one step ahead of having to claiming poor relief for herself and her children, struggling to keep them fed, safe and out of trouble. This was a far cry from the quiet hopes she and Daniel might once have shared. But Julia had grown tougher with each passing year. She might have been a police constable’s widow, but she was also more than capable of standing her ground.

One April afternoon in 1885, she returned home to find a man — Patrick Cane, a labourer — coming out of her house. When she demanded to know what he was doing, he claimed it was a mistake. Julia was having none of it. “A funny sort of mistake,” she said sharply, “seeing as it’s the third time”. Cane, who lived next door and was very drunk, didn’t take kindly to her challenge. He punched her in the face, drawing blood. But Julia didn’t cower — she struck him right back![xxvi]

Later, she reported the assault and had him arrested on a warrant. When the case came before the magistrate, Cane admitted being drunk and making a “mistake,” but Julia’s version of events left little room for sympathy. As the legal proceedings unfolded, it emerged that Cane had a history of violence and had also assaulted his own wife — badly enough to break each of her arms on two separate occasions.[xxvii] [xxviii]

It’s a telling episode: Julia would not be intimidated. She protected her home, stood up to violence, and ensured her voice was heard. Despite all life had thrown at her, she remained fiercely independent — a woman of sharp instincts, capable of defending herself when she needed to.

Julia stayed in her rooms in Walham Avenue for about ten years. Like much of Fulham, which was still a relatively new town — its open fields and market gardens paved over with thousands of houses in the space of a generation – the area had declined. Already, struggling, it had taken a turn for the worse — overcrowded and unsanitary, with crime and alcohol-fuelled violence a daily reality. The 1889 social survey described Walham Avenue as one of the “Poor Avenues off N. side of Fulham Road”, with “windows broken, patched, doors open, women and girls in frayed skirts & hatless, foetid smell of dirt, costers barrows, vile place.” [xxix]

Another clue to Julia’s tenacity and independence lies in the 1889[xxxi] Electoral Roll, compiled ahead of London’s first County Council elections. Only two women on Walham Avenue were registered to vote — and Julia was one of them. As a widow and tenant in her own right, she may have qualified through paying the local rates. Illiterate or not, she was likely helped to register by one of her older children or a neighbour, and with their support, it seems she was determined to make her mark – quite literally – by placing her familiar ‘X’ on the ballot paper.

By the time of the 1891 census[xxxii], Julia, now aged 53, was working as a self-employed laundress — washing and ironing clothes for more affluent households to earn a living. The census notes that she was neither an employer nor employed, suggesting she was working for herself, perhaps taking in washing from neighbours or through informal local networks.

Only two of her children were still living at home in Walham Avenue: Elizabeth, now 20 and working in general domestic service, and Daniel, 18, employed as a grocer’s porter[xxxiii]. The older children had now grown up and begun lives of their own. Her eldest son Edward, a postman, married Ellen in 1884; they now had four children — Daniel Leonard, Lucy, Margaret, and Edward — and were living nearby[xxxiv]. James, aged 23, who married a couple of years earlier in North London, had returned to Fulham with his wife Nelly and their baby daughter, named Julia after her grandmother. They, too, were living just a few streets away, with James working as a yard labourer at the local gas works[xxxv].

A couple of years later, in 1893, Elizabeth married William Banfield[xxxvi], a young carman for a delivery company, who lived next door, and they would soon start a family of their own — with my grandmother as one of their eight children.

By 1901[xxxvii], Julia had moved to Walham Yard. She was 64 and still working for herself as a laundress. Her youngest son Daniel, 27 and a coachman working with horses, was still at home, and the household included Kate Neay, a 40-year-old cook from Ireland, who was staying as a visitor, and a boarder, Harry Harding, a 28-year-old cab driver from London.

Daniel married Alice[xxxviii] a few months later, leaving Julia alone for the first time in nearly forty years.

In March 1909, tragedy struck when Julia’s daughter Elizabeth died[xxxix] aged just 38, leaving a husband with a young family to provide for. Julia may have tried to help but her age and finances were against her.

That same year, however, brought a glimmer of support with the introduction of the old age pension. Julia, by now over 70 , met the qualifying criteria: she had lived in Britain for more than 20 years, was “of good character” (not habitually drunk, in prison, etc.), earned less than 12 shillings a week, and had not received poor relief in the previous year. The maximum pension was just five shillings a week, not much, but it was the first time the state offered support to older people without them having to go into the workhouse[xl]. Having managed all her life to avoid the stigma of poor relief, Julia likely applied for the pension – perhaps with help from one of her children or grandchildren.

As the years passed, she became less able to live independently. The 1911 census[xli] finds her aged 73, described as an “old age pensioner” lodging at 63 Burnthwaite Road, Fulham, with Annie James a widow and charwoman, and her unmarried son Alfred Henry James, 37, a harness maker.

Ten years later, in 1921[xlii], Julia – now 82 – is recorded as a widow of “small means”. She is lodging at 50 Burnthwaite Road in the home of Alice Barker, a 46-year-old widow and school cleaner, along with Barker’s five children aged between 13 and 24. Julia’s granddaughter, Margaret Banfield (Elizabeth’s daughter), a charwoman aged 27, was also living there with her.

Julia died in 1925 of ‘senile decay’ (dementia) and bronchitis aged about 84 – a grand age for the time. Her death certificate[xliii] records that her eldest son Edward, by then a retired postman in his mid-sixties, came from his home in Worcester to be with his mother at the end of her life.

I have a huge amount of respect and admiration for Julia, and the way she lived her life: the hopes, the dreams, and the overwhelming sadness for what could have been. And her strength: the quiet determination to do the right thing and help her children and grandchildren to reach their full potential.

Ultimately, what mattered was not how her name was spelled, but how she lived. Julia’s story is an extraordinary one, with threads stretching from the rolling fields of Cork to the smoke and slums of Fulham. She raised a family, endured hardship, and—unbeknownst to her—left a legacy written in more than just official records.

[i]Ireland Roman Catholic Parish Marriages > Liscarroll, Cloyne, Cork, Ireland via findmypast.co.uk

[ii] Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

[iii] https://www.patrickcomerford.com/2020/09/liscarroll-castle-now-in-ruins-but-once.html last visited 16 Apr 2025

[iv] https://brentfordandchiswicklhs.org.uk/search-discover/chiswick-history-homepage/gill-cleggs-brief-history-of-chiswick/ last accessed 17 Apr 2025

[v] 1861 England Census Middlesex > Chiswick > District 5 via ancestry.co.uk last visited 16 Apr 2025

[vi] https://maps.nls.uk/ Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence last visited 16 Apr 2025

[vii] https://maps.nls.uk/ Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence last visited 16 Apr 2025

[viii] https://edithsstreets.blogspot.com/2017/12/chiswick-turnham-green-and-acton-green.html last visited 16 Apr 2025

[ix] GRO birth certificate for Patrick Fitzgerald 1866 Q4 Brentford, Middlesex, Vol 3a p79

[x] GRO birth certificate for James Fitzgerald 1868 Q3 Brentford, Middlesex, Vol 3a p88

[xi] National Archives (TNA): Return of deaths in the Metropolitan Police Force Ref: MEPO-4-2 page 42

[xii] https://historybytheyard.co.uk/mpd1860.htm last visited 16 Apr 2025

[xiii] https://www.victorianlondon.org/police/policeoflondon.htm last visited 16 Apr 2025

[xiv] Ibid

[xv] https://www.thegenealogist.co.uk/featuredarticles/discover-your-ancestors/periodical/78/history-in-the-details-police-uniforms-6706/ last visited 16 Apr 2025

[xvi] GRO birth certificate for Elizabeth Fitzgerald 1871 Q1 Kensington (sub district Fulham), Middlesex, Vol 01A p229

[xvii] https://www.cottontown.org/Health%20and%20Welfare/Pages/PC-23-Charles-Whitehead.aspx last visited 16 Apr 2025

[xviii] 1871 England census RG10/69/84/11 via ancestry.co.uk last visited 16 Apr 2025

[xix] Fulham old and new: being an exhaustive history of the ancient parish of Fulham by Charles James Feret – 1900 https://archive.org/details/fulhamoldandnew00frgoog last access 05 Aug 2021

[xx] Perityphlitis and its surgical treatment by Herman Mynter, published 1890 via archive.org

[xxi] GRO death certificate for Daniel Fitzgerald 1879 Q3 Fulham, London, Vol 1a p 136

[xxii] Kensington News and West London Times 26 Jul 1879 via findmypast.co.uk last accessed 17 Apr 2025

[xxiii] Wikipedia > Police Act 1890 last accessed 17 Apr 2025

[xxiv] 1881 England census RG11/ 74/16/32;GSU roll: 1341016 via ancestry.co.uk last accessed 17 Apr 2025

[xxv] George H. Duckworth’s Notebook: Police District 28 [Kensington Town], District 29 [Fulham], District 30 [Hammersmith] BOOTH/B/361, p. 219 via https://booth.lse.ac.uk/ last accessed 17 Apr 2025

[xxvi] West London Observer 04 July 1885 via findmypast.co.uk last accessed 14 Dec 2023

[xxvii] West London Observer 18 July 1885 via findmypast.co.uk last accessed 14 Dec 2023

[xxviii] Derry Journal 03 Mar 1884 via findmypast.co.uk last accessed 14 Dec 2023

[xxix] George H. Duckworth’s Notebook: Police District 28 [Kensington Town], District 29 [Fulham], District 30 [Hammersmith] BOOTH/B/361, p. 173 via https://booth.lse.ac.uk/ last accessed 17 Apr 2025

[xxx] Charles Booth’s poverty map (1886-1903) via https://booth.lse.ac.uk/map last accessed 18 Apr 2025

[xxxi] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Electoral Registers > Hammersmith & Fulham > Fulham > Moore Park > 1889 via ancestry.co.uk

[xxxii] 1891 England census RG12/50/ 95/52 GSU roll: 6095160 via ancestry.co.uk

[xxxiii] Ibid

[xxxiv] 1891 England census RG12/50/ 80/22 GSU roll: 6095160 via ancestry.co.uk

[xxxv] 1891 England census RG12/51/ 133/31 GSU roll: 6095161 via ancestry.co.uk

[xxxvi] GRO marriage certificate for Elizabeth Fitzgerald and William Banfield 1893 Q3 Fulham Vol 1a p697

[xxxvii] 1901 England census

[xxxviii] London, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1921 > Parish Register > Saint Matthew, West Kensington: Sinclair Road, Hammersmith and Fulham, England > Parish Register > Reference Number 8204511 Additional Reference Number 428633 via ancestry.co.uk

[xxxix] GRO death certificate 1909 Q1 Fulham Vol 01a p 299

[xl] Wikipedia Old Age Pensions Act 1908 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Age_Pensions_Act_1908 last accessed 19 Apr 2025

[xli] 1911 England census Registration District 3, Sub-registration District Fulham, ED 27, Piece 330 via ancestry.co.uk

[xlii] 1921 England census GBC_1921_RG15_00351_0583 via findmypast.co.uk

[xliii] GRO death certificate Julia Fitzgerald 1925 Q1 Fulham Vol 1a p450