Click here to go back to the previous chapter

Warning: some readers may find aspects of this story distressing

By early January 1945, the Soviet Army’s rapid advance from the east pushed Germany to evacuate its POW camps. Prisoners were marched hundreds of miles west, deeper into central German territory, to prevent their liberation by the approaching Red Army.

For 25-year-old Ted Mayhew, a former electrician from Fulham in South West London, this gruelling trek was yet another chapter in a captivity that had begun in 1940. Conscripted into the Army at 20, Ted served as a gunner with the 140th Field Regiment of the Royal Artillery. During the heroic but doomed rearguard action at Cassel, a hilltop town south of Dunkirk, his unit was effectively sacrificed to delay the German advance, enabling the evacuation of nearly 340,000 British and French troops. Captured after fierce resistance, Ted was sent to Stalag VIIIB (later renumbered 344) at Lamsdorf, Upper Silesia (now Lambinowice, Poland), and later transferred to Work Camp E72 in Beuthen (now Bytom, Poland). There, alongside up to six hundred other men, he endured the brutal degradation of forced labour in a coal mine.

Despite the cramped conditions and lack of nutritious food during their years of incarceration, Ted and his fellow POWs managed to adapt to a grim routine. They endured exhausting shifts underground at the coal face, then fought to stave off boredom, anger, and depression in their few moments of rest.

Now, in the final, desperate months of the war, this hard-won equilibrium would be shattered once again. On 17th January 1945, the Red Army captured Warsaw. Within hours, the German command ordered the evacuation of nearly 60,000 inmates from the notorious Auschwitz concentration camp, including women, Jewish prisoners, and Polish children[i]. While some were deported by rail, others were forced to walk through freezing temperatures. Many did not survive the ordeal.

At the same time, over a quarter of a million British, Commonwealth, and American POWs[ii], collectively nicknamed ‘kregies’[iii] – were held across fifty-five camps and seven hundred subsidiary Arbeitskommandos (work camps) in what are now southern Poland and northern Czechia. Among them, approximately 80,000 POWs were forced to join the gruelling ‘Long March’[iv] trudging along three main evacuation routes that spanned an area of more than 1,300 km2 (over 500 square miles). Years of inadequate rations had left most men physically unprepared for the evacuation, and their few items of clothing offered little protection against the appalling winter conditions.

Those deemed by the camp commandant to be too ill or weak to walk were left behind. Some were later evacuated by rail or eventually liberated by Soviet troops in March 1945[v].

On Monday 22nd January 1945[vii], Ted was among two to three hundred POWs – mostly British, but with some Allied and Russian men – who marched out through the main gate and onto the main road to form up into a column. The notorious camp comandant, ‘John the Bastard’, was conspicuously absent that day[viii]. Instead, a German ‘feldwebel’ (a non-commissioned officer equivalent to a British Army sergeant) took charge of the column, accompanied by a handful of guards on foot, each carrying rifles[ix].

Neither the prisoners nor guards knew their destination or what lay ahead. However, they had seen the distant flashes of artillery and heard the bursts of shell fire as the Soviet Army advanced rapidly towards the German border. For the guards, the Soviets represented retribution – a fear of capture and harsh punishment for their role in the Nazi regime loomed large. For the prisoners, stories of Soviet brutality had been circulating, and the chaos of being caught in the crossfire of advancing forces brought its own terrors.

Although several memoirs of POWs who took part in the Long March have been published or recorded over the past eighty years, it has not been possible to pinpoint exactly which group Ted was in, nor the route he took. However, he could easily have been in the same group as fellow E72 prisoner Frederick Linaker, who recorded an oral history for the Imperial War Museum some years ago[x].

Frederick described leaving the camp wearing his uniform trousers and battledress tunic, which had survived thanks to his use of ‘pit clothes’ during shifts down in the coal mine. He also wore his only pair of underpants and socks, a great coat, and carried one thin blanket. With no hat or gloves for warmth, he brought his few personal possessions – a photograph of his wife and a couple of odds and ends – in a Red Cross parcel box. He recalls that, as they left the camp, each man was handed a lump of black bread, a chunk of sausage meat, and a piece of cheese[xi]. Most of his fellow POWs were similarly dressed and equipped, their boots often supplied through the British Government or other sources arranged by the German camp authorities to replace those worn beyond repair.

The columns of men were forced to march, or rather trudge, up to 30km (nearly 20 miles) a day, following rural lanes and skirting towns. Blinding snowstorms sometimes swept through, but the bitter cold was constant[xiii]. Early 1945 was one of the coldest winters in European history, marked by ferocious blizzards and temperatures plunging as low as -25 °C (-13 °F).

At dusk, the men would stop and camp in barns – hopefully lined with a little straw – or farm outbuildings. There was no heating and little food, but they sometimes managed to scavenge a few potatoes or swedes, boiling them in the farm’s pig-swill boiler to make a weak soup. At night, they huddled together, sharing what little body heat they could, often lying on bare floors or straw if it was available.

Boots soon became a major problem. Blisters went untreated, and once boots wore out, there was no way to repair them. Some men tore strips from blankets to wrap around their feet, trying to reinforce what was left of their footwear[xiv]. Leaving damp, cold boots on overnight risked trench foot, but removing them posed other dangers: swollen feet might not fit back into them by morning, or the boots could freeze solid – or worse, be stolen.

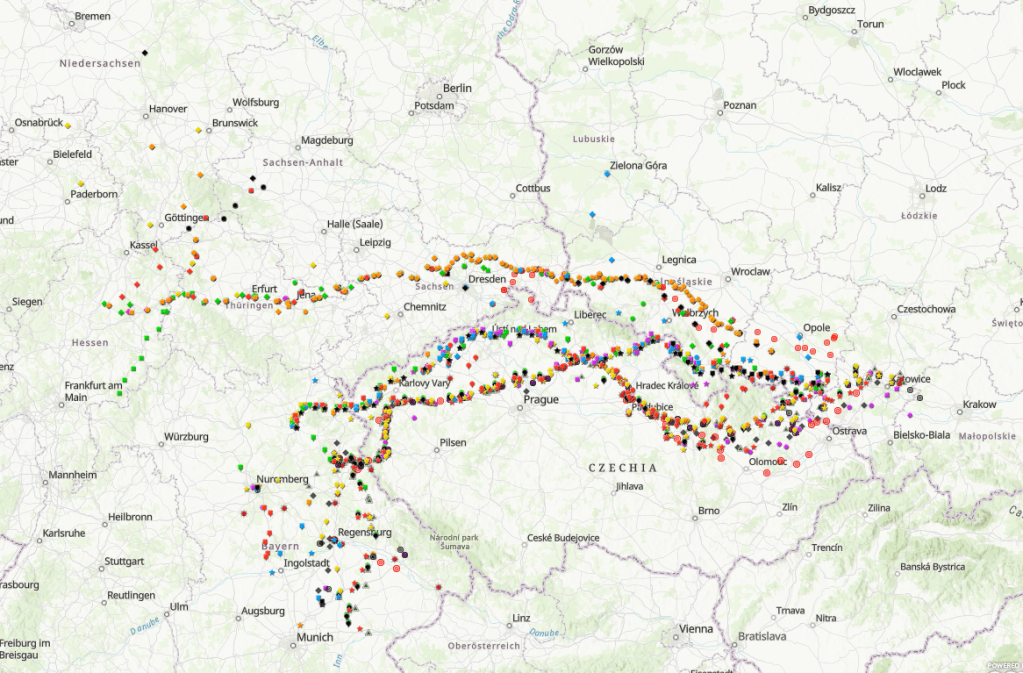

The above screenshot shows some of the different routes taken by forty-eight men on the Long March. For more information and maps please visit Taking the Long Way Home website (link opens in new tab).

On and on, day after day, the men trudged in a general westerly direction, shuffling along in rows three or four deep. The roads were flanked by high drifts of snow, but the feet of the men in front had trampled the snow on the ground into treacherous ice as slick as a skating rink. The bitter cold made their eyes water and freeze shut, their breath crystallised in the air, and their faces were crusted with hoar frost, with icicles hanging from their beards.

When a man faltered and fell out of line, his mates might nudge him in a desperate attempt to keep him moving, but there was little they could do. Vomiting and dysentery, caused by the lack of clean drinking water, were widespread, but there was no medical treatment – nor mercy. Sanitary arrangements were non-existent, leaving men to relieve themselves quickly by the side of the road before a guard forced them back into line at gunpoint[xvi] .

Accounts from the time recount the especially brutal treatment of Russian POWs. Guards showed no interest in them, and many hundreds simply collapsed and died, their bodies frozen stiff where they fell. Some were even shot outright by the guards.

Back in Britain, the War Office was aware of the mass movement of POWs, and short reports of their progress occasionally appeared in the press. By late February, the families of Lamsdorf prisoners were aware that their loved ones were on the move, and anxiously awaited updates.

Meantime, hour after hour, the prisoners tramped on, conserving energy by staying silent. Blindly following the man in front, the desperate columns stuck to lanes and minor roads, avoiding towns and villages as they moved in the general direction of Berlin. When they stopped overnight, their conversations often revolved around how many miles they had covered, how much further they might have to go, and whether there would be anything to eat the next day[xviii].

The routes taken by different groups were far from straightforward, with frequent meanderings and even circling back to previous stopping points. Occasionally, the column would halt, and the men were forced to work repairing bomb-damaged railway tracks or other infrastructure, often under the threat of Allied strafing from the air or bombing runs.

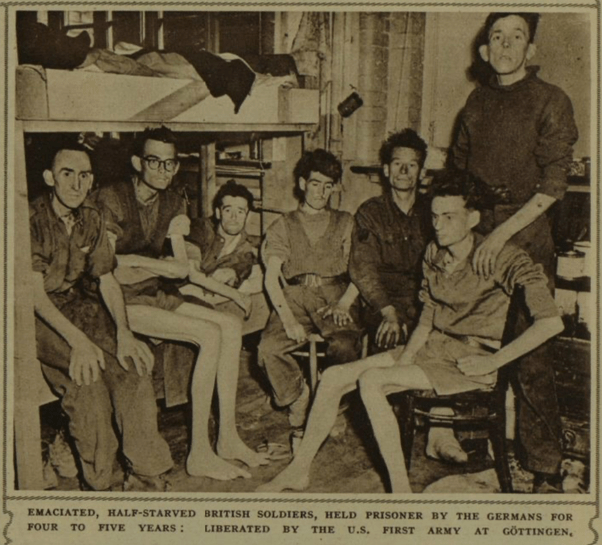

As they progressed further west, a thaw began to set in, turning the snow on the ground to cold, clinging slush. While frostbite became less of an issue, the men’s boots – mostly riddled with holes and falling apart – left their feet perpetually soaked, increasing the risk of trench foot. Hygiene was non-existent; none of the men had removed their shirt or underwear for over two months, and all were crawling with lice and fleas. Starvation took its toll, with many having lost between a third to half their pre-war body weight. Adding to their misery was the constant Allied air attacks, as their column could be easily mistaken for retreating German troops.

Eventually, about three months after leaving E72, Frederick Linaker’s group reached Bavaria, a little to the east of the city of Regensburg. Regensburg had been heavily bombed by the RAF, and they bridge they should have crossed was down so they stopped to rest for the night not knowing where they would go next[xix].

The following morning, probably the 1st of May 1945 – the day after Berlin fell to the Red Army and Germany’s Nazi leader Adolph Hitler reportedly committed suicide in a Berlin bunker – the men in Frederick Linaker’s group awoke to discover their guards had fled and a truck full of American troops was approaching[xx].

As front-line soldiers, the Americans could initially offer little more than chocolate and cigarettes, but back-up transport soon followed. The newly liberated men were loaded into lorries and taken to a nearby airfield to await onward transport. As the airfield had recently been bombed, there were no huts, no tents, nor facilities, however they were eventually transferred in batches of up to fifty at a time by troop plane to an American transit camp near Reims in France.

In the transit camp there was no real opportunity to wash or proper clean up, and the men were still wearing the same filthy, lice- and flea-ridden clothes they had worn for months. Fortunately, a 24-hour canteen provided them with the chance to line up for a decent meal, but all they truly wanted was go home. Processing and repatriating the hundreds, if not thousands, of men from Britain and other nations must have been a logistical nightmare for the Americans.

Germany’s unconditional surrender of its armed forces was formally accepted by the Allies on Tuesday, 8th May 1945—Ted Mayhew’s 26th birthday—now remembered as VE Day, marking Victory in Europe. Before boarding the Lancaster bomber that would take him back to England, Ted and his fellow liberated POWs underwent processing by military personnel. This included being treated by an orderly armed with a DDT delousing gun, who pumped insecticide powder down their trousers, under their arms, and through their hair.

Upon landing, the men descended from the plane and were taken to a Reception Centre where they were stripped, given a hot bath, a haircut and shave, a full medical examination, and a new uniform. The uniforms hung loosely on their emaciated bodies, a sark reminder of the weight they had lost during their ordeal.

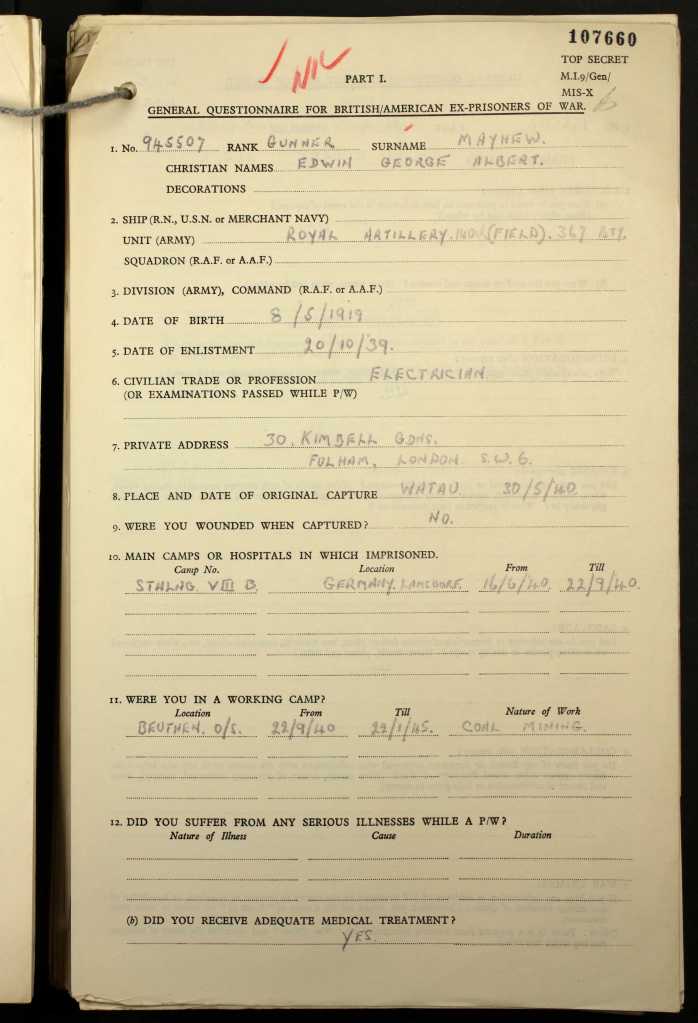

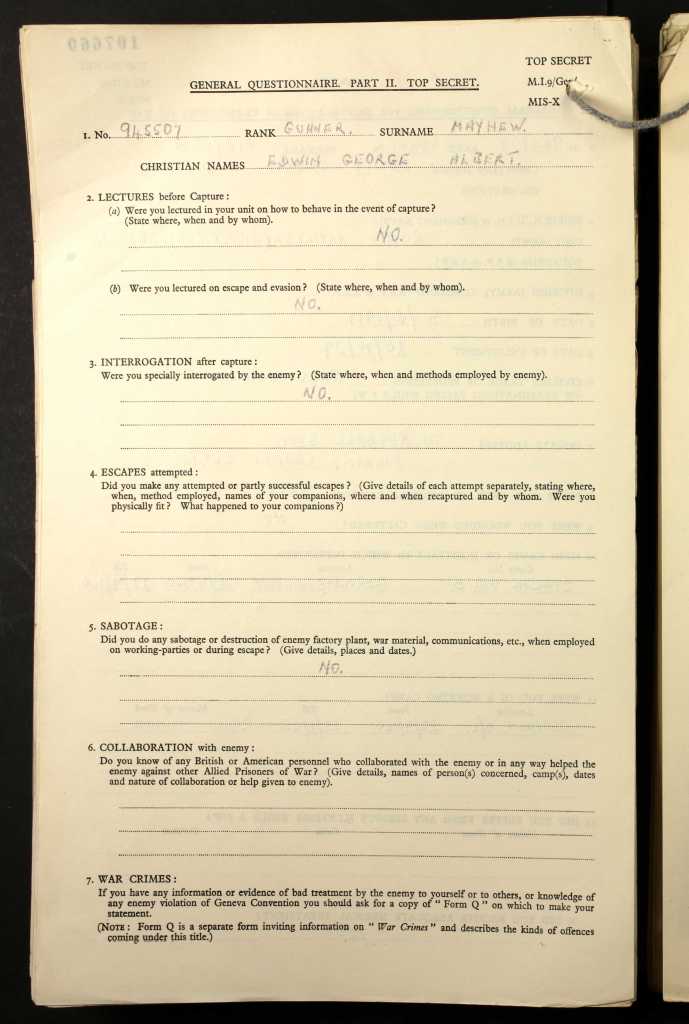

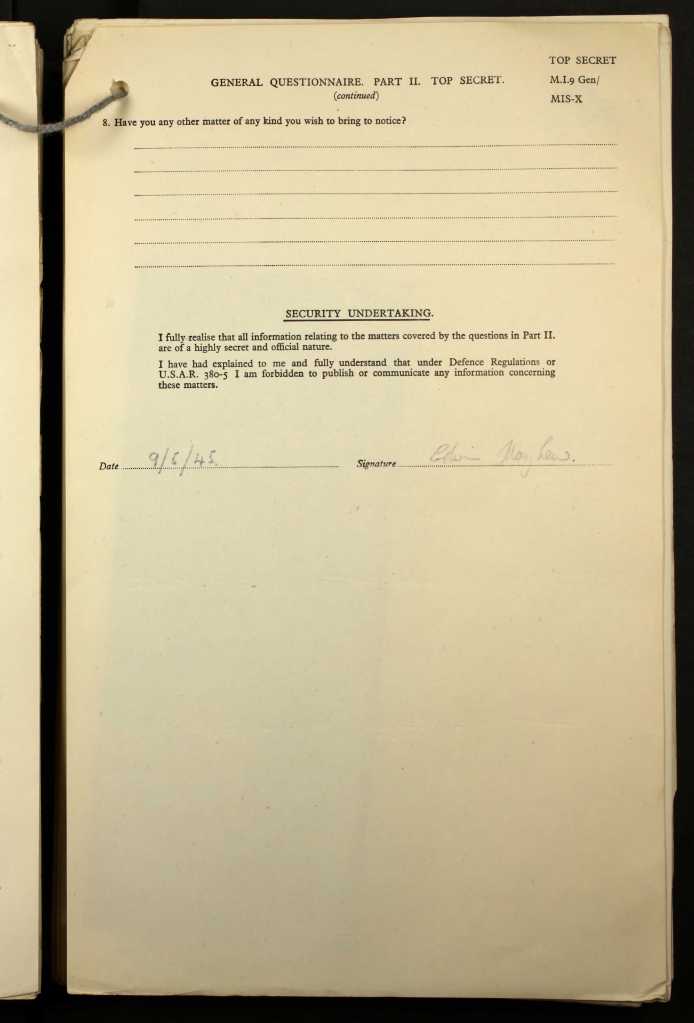

Nevertheless, Ted was still a serving soldier. As such, he was interviewed by MI9, the British military intelligence branch working alongside its American counterpart, MIS-X. Newly released POWs were seen as a potential source of valuable intelligence, which could aid in prosecuting of war crimes. Upon arrival at the Reception Centre, every returning POW was supposed to complete a detailed questionnaire. However, only about 50% of them complied, with the remainder managing to somehow avoid this.

The questionnaire was divided into two parts. Part One gathered basic information: the date and place of capture, camps and hospitals where they had been held, work assignments, and any significant illnesses or medical treatment. Part Two, marked ‘Top Secret’, asked about escape attempts, sabotage, ill-treatment, torture, and help received from civilians. This section also included a Security Undertaking to keep the information contained therein strictly confidential. Ted’s responses to these questions were sparse, limited to simple ‘No’ answers or left blank. His reluctance to engage may have stemmed from exhaustion, trauma, mistrust, or a determination to leave the past.

Below are links to Ted’s completed questionnaire[xxii], click on an image to view full sized (click the cross top r/h side to close):

Although he now weighed less than 40kg (about 6 stone)[xxiii], was deaf in one ear after an altercation with a German officer, had endured years of starvation and forced labour in a coal mine, and the harrowing Long March, Ted was deemed medically fit and remained on active duty. He was issued with a forty-two-day compassionate leave pass and railway ticket to return home briefly.

Although Germany had surrendered and the war in Europe was over, the conflict in the Far East raged on. Demobilisation would have to wait, as liberated POWs like Ted were expected to recover and prepare for the planned invasion of Japan. This operation also aimed to liberate territories such as Singapore, Malaya, and the Dutch East Indies, as well as to free the Far East POWs who were enduring unimaginable hardships of their own.

Click here to read the final chapter

There are a couple of excellent websites created by the sons of other survivors of the Long March:

- 140th (5th London) Army Field Regiment, Royal Artillery created John West, whose father Eric served in the same unit as Ted Mayhew and they appear together in several photographs during their time in Stalag VIIIB

- Taking the Long Way Home which features an interactive map of the Long March showing the routes followed by forty-eight survivors from Stalag VIIIB and its many work camps.

[i] https://www.auschwitz.org Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum last accessed 18 Dec 2024

[ii] The March (1945) via https://en.wikipedia.org last accessed 12 Dec 2024

[iii] ‘kriegie’ (noun) slang for Allied prisoner of war in Germany during the war of 1939–45, via www.oed.com last accessed 12 Dec 2024

[iv] The March (1945) via https://en.wikipedia.org last accessed 12 Dec 2024

[v] Evacuation of Prisoner of War Camps via www.lamsdorflongmarch.com last accessed 12 Dec 2024

[vi] Image HU 47248 © Imperial War Musuem via www.iwm.org.uk last accessed 16 Dec 2024

[vii] TNA Ted Mayhew’s Liberated POW Questionnaire WO 344/215/2

[viii] Ibid

[ix] Ibid

[x] Frederick Linaker oral history recording 11750 via www.iwm.org.uk/ last accessed 13 Dec 2024

[xi] Ibid

[xii] Australian War Memorial accession number ART25519 via www.awm.gov.au copyright expired, image in the public domain

[xiii] Frederick Linaker oral history recording 11750 via www.iwm.org.uk/ last accessed 13 Dec 2024

[xiv] Ibid

[xv] https://www.lamsdorflongmarch.com/ > The Lamsdorf Long March Maps last accessed 09 Jan 2025

[xvi] Frederick Linaker oral history recording 11750 via www.iwm.org.uk/ last accessed 13 Dec 2024

[xvii] Daily Herald – 27 Feb 1945 via www.findmypast.co.uk

[xviii] Frederick Linaker oral history recording 11750 via www.iwm.org.uk/ last accessed 13 Dec 2024

[xix] Ibid

[xx] Ibid

[xxi] Illustrated London News – 21 Apr 1945 via findmypast.co.uk

[xxii] TNA: Directorate of Military Intelligence: Liberated Prisoner of War Interrogation Questionnaires, 1945-1946; Piece Number: WO344/215/2 images © National Archives

[xxiii] Family oral history as recalled by Pauline Weir, Dec 2024