Click here to go back to Catherine Dibben’s Overview

When Catherine was born on 24th May 1850, her parents Isaac and Mary Ann (née Cooper) already had six children – four girls and two boys.[i] Her father was 39-year-old agricultural labourer who received a substantial award later that year of £2 10s from the Bishop of Winchester “for having supported seven children with only 13s 4d relief”.[ii] It was her mother who registered the birth, marking the register with an ‘X’ in place of a signature,[iii] a small but telling sign of her lack of education, as she could not read nor write. It would be another twenty years before the Elementary Education Act of 1870, commonly known as Forster’s Education Act, laid the foundation for compulsory schooling for children aged five to twelve in England and Wales.[iv]

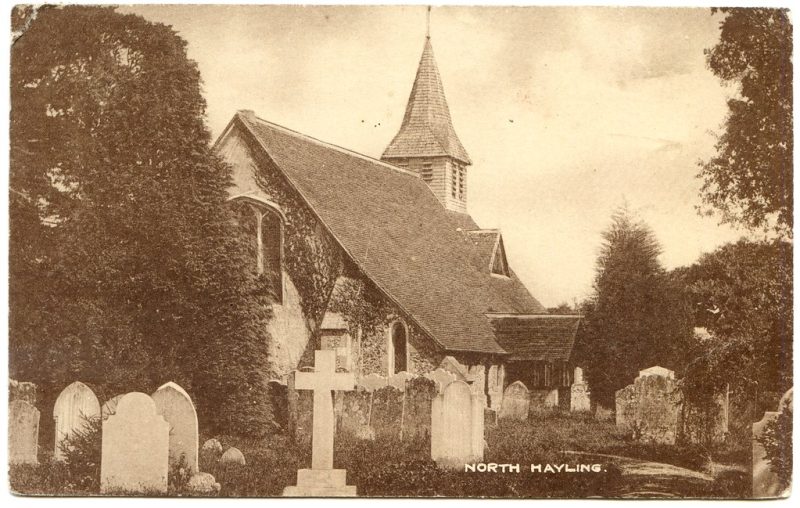

During the 1850s, three more daughters were born to the family, and Isaac – by then also serving as parish clerk at St Peter’s church – received two further awards from the Bishop of Winchester for bringing up his family with the smallest amount of help from the parish.

By the time of the 1861 census,[vi] Catherine was ten years old. She, her thirteen-year-old sister Mary Ann, and their three younger sisters were all recorded as scholars, suggesting that their parents were determined to see their daughters educated, even at a time when schooling was neither free nor compulsory. Their brothers, sixteen-year- old Henry, fifteen-year-old William, and Joseph, Mary Ann’s twin, were already listed as farm servants, reflecting the economic reality that boys were expected to contribute to the family income as soon as they were able.

Throughout Catherine’s early years, her father laboured for Thomas Rogers, a local farmer. It has not been possible to pinpoint the exact location of the family’s tied cottage, but like many in Hampshire, it was probably built of red brick and flint. [vii] In this region, flint was valued for its strength and resistance to weather, especially when bound with a good lime mortar. However, when brick was used on the outside of a cottage for appearance’s sake, with flint and limestone forming the inner walls, the structure was more vulnerable to damp. The porous brick absorbed rainwater and, once saturated, could leach through to the flint and limestone on the inside. Many cottages built in this way suffered badly, particularly in winter when moisture condensed on cold internal walls.

The Dibben family home probably consisted of three or four rooms on a single storey, with a floor of brick, old ship planks, or lime ashes mixed with pounded chalk, and a thatched roof. Cottages were generally in good supply in the area, so it was unusual for more than one family to share a dwelling. Even so, with two adults and ten children under one roof, it would have felt crowded enough.

Yet for all the bustle and noise of such a large family, life on a rural island was precarious. Disease, accident, and misfortune could strike at any time, and few families escaped untouched. Despite the apparent steadiness of country life, Catherine grew up in a world where death was an all too familiar presence.

The first death likely to have touched her family was that of her eldest sister Jane, aged seventeen, who died after suffering from typhus fever for ten days in 1859,[ix] when Catherine was nine years old. Typhus is a group of bacterial infections spread by lice, fleas, or mites. Symptoms include high fever, headache, a rash, nausea, and an overwhelming sense of weakness. Today it can be treated with antibiotics, but in the 1850s there was no known cure, and mortality rates were high.

Jane’s death was reported by their neighbour Sarah Barber, the 59-year-old wife of a local carrier. It is possible that Mrs Barber had some experience as a nurse or midwife and was called in to help during Jane’s illness, especially if Catherine’s mother was exhausted or overwhelmed by caring for so many children. In rural communities it was common for a respected neighbour or tradesman’s wife to act as an informal “nursewoman” when illness struck. Sarah may have tended to Jane in her final days and then taken on the practical duty of reporting the death to the registrar, perhaps as a kindness to the grieving family. However, Jane’s cause of death was recorded as “certified”, indicating that a qualified physician had signed a medical certificate confirming the cause.

The second death to touch the family came in March 1870, when Catherine’s brother Joseph died suddenly. Catherine, who was by now married and had moved away, was two years younger than twenty-two-year-old Joseph and his twin sister, Mary Ann. Sadly, Joseph took his own life by hanging and, at the inquest, the jury found “no evidence as to his state of mind at the time”.[x] This must have been a terrible blow. Their father was the parish clerk at St Peter’s Church in North Hayling, yet Joseph was buried in the next parish of South Hayling – perhaps to avoid local attention, or because church regulations then in force made it difficult to bury someone who had died by suicide in consecrated ground.[xi]

Life expectancy was slowly increasing in the second half of the nineteenth century,[xii] rising from about 40 for males and 42 for females in 1841, to 44.5 for males and 52.4 for females by 1901. However, these averages were heavily influenced by the high number of infants and young children who died before the age of five. Among those who survived childhood, it was not unusual to live into one’s seventies or even eighties.

Catherine’s own family reflects this pattern. Following the premature death of her brother Joseph in 1870, there seem to have been no further bereavements in her close family for more than twenty years – a period during which Catherine herself moved into a new phase of life, shaped by marriage and separation from her childhood home.

Click here to read the next chapter

[i] England 1851 Census HO107/165632/7 via ancestry.co.uk

[ii] Hampshire Telegraph & Sussex Chronicle – Sat 27 Sep 1851 via findmypast.co.uk

[iii] Full birth certificate from GRO (pdf)

[iv] The Elementary Education Act 1870 via en.wikipedia.org last accessed 24 Oct 2025

[v] postcard via www.flickr.com

[vi] England 1861 census RG9/631/23 via ancestry.co.uk

[vii] General view of the agriculture of Hampshire, including the Isle of Wight by Charles Vancouver published 1810 by R Philps, London, via archive.org

[viii] Image via www.ebay.co.uk

[ix] Digital death certificate from GRO

[x] Chichester Express and West Sussex Journal 29 Mar 1870, copy death registration from GRO

[xi] South Hayling Parish Records via ancestry.co.uk

[xii] Life expectancy at birth, England and Wales, 1841 to 2011 via https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/articles/howhaslifeexpectancychangedovertime/2015-09-09 last accessed 6 Oct 2025