Click here to go back to the previous chapter

Catherine had left Hayling Island in 1869 as a young married woman and returned some twenty years later. During her absence, the flat, largely agricultural island had changed considerably. Although horse-drawn transport still linked it to Havant, the main gateway to the mainland, a town served by two busy railway lines: the London, Brighton & South Coast line through Portsmouth (since 1847) and the London & South Western line from Waterloo (since 1859).

According to White’s Directory of Hampshire (1878),[i] Hayling now held 1,139 inhabitants and 3,887 acres of land, divided into two parishes: North Hayling, where Catherine was born, and South Hayling, where she would spend the rest of her life. Along the southern shore, seaside villas and boarding houses were springing up beside what the directory described as “one of the finest beaches in the south of England”, the sands “so firm that carriage-wheels make but a faint impression”.[ii]

Farming, salt- and brick-making, and fishing had long supported the islanders, but by the late nineteenth century machinery was replacing manual labour, and the railways were opening the coast to visitors. Grand hotels rose beside modest guest houses catering to families and single travellers. South Hayling boasted a bank, post office, and library, along with a picture gallery and even a chess room, [iii] while the more rural North Hayling could still list only a handful of farmers and tradesmen – among them Catherine’s father, the parish clerk.

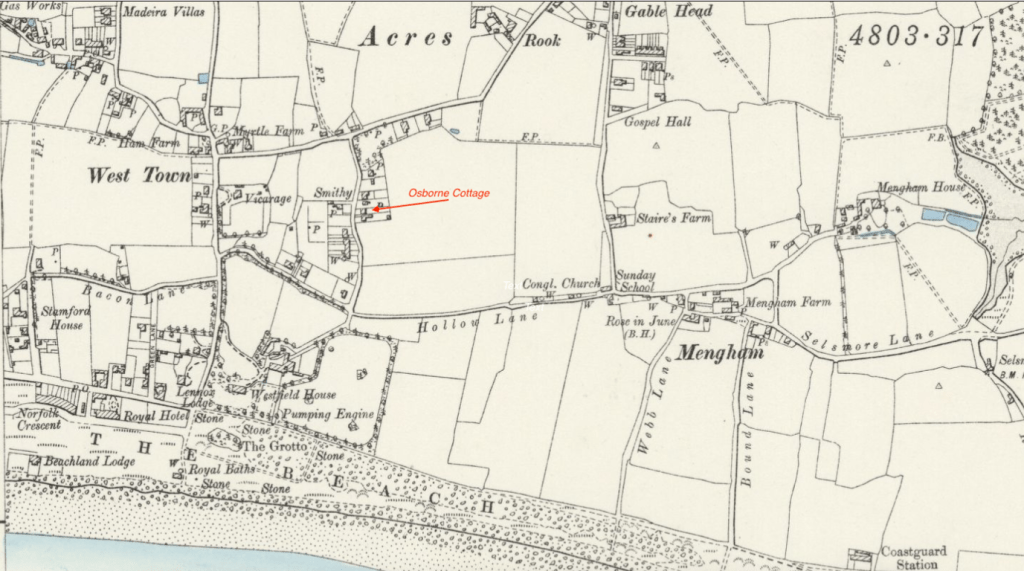

By 1891 Catherine and her family were back on the island, settled at Osborne Cottage on Commercial Road near the seafront.[iv] For the first time she had a home of her own, and one that would also be her livelihood. She ran Osborne Cottage as a boarding establishment for more than forty years.

The property had earlier been managed by Sarah Sparkes, a widow, who had sadly taken her own life after struggling to make it a success. In her final letter to her daughter, Mrs Sparkes wrote “do not bother yourself with a house of this sort”. [vi] Perhaps this unhappy history allowed Catherine to rent it cheaply, but it was still a challenge to turn the business around. By September 1891 she was advertising “two or three furnished rooms; close to sea, rail, and Post Office” – determined to make her new venture work.[vii]

The 1911 and 1921 censuses record Osborne Cottage as having eight rooms, including the kitchen. Still standing today as Osborne Cottage, No. 20 South Road (renamed sometime between 1921 and 1931),[viii] it is a handsome mid-Victorian, double-fronted house, with sash windows, stuccoed façade, and a tiled roof,[ix] solid, respectable, and well suited to its ambitious occupant.

Running a boarding house meant long, demanding days. Catherine would rise before her guests and finish only after they had gone to bed, responsible for every detail of their comfort and the smooth running of the household. She was self-employed, without the protections of later employment law – no guaranteed hours, days off, or sick pay. Her income depended entirely on her ability to attract and retain paying guests, and a quiet season could mean real hardship.

Expenses for food, fuel, repairs, laundry, and any staff wages all came from her earnings. Contemporary newspaper advertisements and census records indicate that Catherine employed a live-in general assistant to help with the daily workload. Her helper would have been responsible for making beds, cleaning rooms, and perhaps assisting Catherine in the kitchen – preparing meals, clearing away, and washing up, but – even with help – the work was physically relentless, and the household relied on coal or wood for cooking and heating, and water drawn from a garden pump shared with the neighbour.

Fortunately, South Hayling was well supplied by local tradespeople:[x] the Barbers’ bakery and grocery, established in 1813 still flourished in the 1930s, and there were several butchers, dairies, and fishmongers selling locally caught produce. Residents left a jug outside for the milkman, who ladled milk from his churn into waiting containers. Like many women of her generation, Catherine probably tended a small garden for vegetables and fruit, kept hens for eggs, and raised a few rabbits for meat – just as her daughter Evelyn would continue to do decades later.

A household guide of 1900[xii] recommended the average weekly consumption per person in an “ordinary family” was half a pound each of sugar, butter, and cheese, six pounds of meat, and up to sixteen pounds of bread for a man. Catherine’s larder must have been kept well stocked to feed her guests three times a day.

Any kitchen scraps or leftovers were reused: fruit and vegetable peelings fed to the hens and rabbits, and other organic waste and ash returned to the garden as compost.

Housekeeping required stamina and pride. Floors were scrubbed with soap and soda, brass polished, and bed linen washed, boiled, and wrung by hand, or put through a mangle. Even with small innovations like the mechanical carpet sweeper (from around 1899) – cleaning remained a constant cycle of physical labour. Gas lighting and running water would have made life somewhat easier in the early 1900s, but not by much.

Beds would be made up daily with a bottom and top sheet, a blanket, and a bedspread. The large hems of the sheets were always placed at the head of the bed so that no guest would ever rest their face where someone else’s feet had been. The bottom sheet was tucked in firmly at the head, smoothed out, and tightly tucked at the foot. The top sheet was then added and tucked in at the bottom only, followed by the blanket, which was placed with a single fold at the head. The top sheet and blanket were folded neatly back to make a smooth edge before the bedspread was laid on top. Finally, the pillows were plumped, set upright at the head of the bed, and the bed was considered properly made.

Laundry was among the hardest and most time-consuming household tasks. In Catherine’s day, washing was usually done once a week – often on a Monday – and could take the best part of the day. Water had to be pumped from the garden and carried into the house in buckets. It was then heated over the kitchen range and poured into a large copper or tub for soaking and boiling the clothes. Stubborn stains were scrubbed on a ridged washboard using a block of soap or washing soda, and the heavy wet linen was lifted out with wooden tongs.

Once rinsed, the clothes were wrung by hand or put through a mangle – a hand cranked machine in which wet laundry, such as sheets, towels, tablecloths and other large items, was fed between two rollers which not only squeezed out the water but helped flatten the fabric. The laundry was then hung outside to dry, weather permitting, or draped over a ceiling mounted airer – often in the kitchen – that could be raised and lowered by hand using pulleys.

Once the laundry was dry, or almost dry, it was pressed flat to remove creases with heavy flat irons – hence the term ironing. The irons were heated in rotation on the range and tested for temperature with a quick touch or a flick of water that hissed if the iron was too hot. While one was in use, a stand or trivet kept another warm and ready for the next turn.

Running Osborne Cottage put Catherine at the heart of island life. Guests brought news from the mainland, and local events offered moments of celebration in otherwise hardworking years.

In 1897, to mark the sixtieth year of Queen Victoria’s reign, sixty horse chestnut trees were planted along Hayling’s new Victoria Avenue. It was a fine day – a great day, full of patriotic rejoicing. A procession of children, ladies and gentlemen set out from the Lifeboat Inn, led by the Hayling Temperance Drum and Fife Band under Thomas Twohey, the postman and former bandsman of the 35th Royal Sussex. His brother, Catherine’s husband Joseph, probably the island’s oldest soldier, was also there, proudly wearing his Crimea and Mutiny medals.

Catherine, however, was not among the spectators. She disapproved of Queen Victoria, having spent much of her married life in barracks on a shilling a day and rations calculated, as she put it, “not to produce fat soldiers.” She was fond of quoting the Queen’s alleged response to Lord Wolseley’s request for higher army pay:

“My goodness, if they are given more they won’t want to die!”[xv]

Although Catherine worked exceptionally hard to make a success of her business, the next decade brought a succession of personal losses. By 1891, Catherine’s father, Isaac had died aged seventy-nine. She was present at his slow death from bronchitis, lung congestion, and exhaustion, and registered this two days later.[xvi] He had served as parish clerk at St Peter’s, North Hayling, for over thirty years and was buried in the churchyard, where other family members may also lie, although their headstones have not survived.

In 1900 Catherine’s elder daughter married but soon returned home gravely ill with tuberculosis, dying the following year aged just twenty-one.[xviii] Soon after, her mother Mary Ann died aged eighty-one, [xix] followed by her sixty-year-old brother-in-law Thomas, who succumbed to cancer of the tongue. [xx]

Catherine and Joseph’s younger daughter, Evelyn, married Harry Collingwood in June 1903, and moved to Italy with her new husband, where three children were born – grandchildren Catherine probably never met for nearly a decade. It’s unlikely that Catherine had much leisure time. As well as her duties caring for her immediate family, running the boarding house remained extremely hard physical work, and I can’t help but wonder if sitting in church on Sunday for a couple of hours was the most rest she could hope for.

Click here to read the next chapter

[i] History, gazetteer and directory of the county of Hampshire, including the Isle of Wight (2nd edition) by William White, published 1878 by Simkin, Marshall & Co, London, via babel.hathitrust.org

[ii] White’s Hampshire 1878 directory as above.

[iii] I Remember When It Was Just Fields’ The Story of Hayling Island by Ron Brown published 1983 by Milestone Publications, Hampshire.

[iv] 1891 England census RG12/852/27

[v] map via National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/view/101442006 reused under Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence.

[vi] report of the inquest into the death of Mrs Sparkes in several newspapers in Feb 1889 via findmypast.co.uk

[vii] Portsmouth Evening News, 16 and 21 Sep 1891 via findmypast.co.uk

[viii] 1921 census still Commercial Road, but renamed by 1931: OS Map Hampshire and Isle of Wight LXXXIV.11 Revised: 1931, Published: 1932 via maps.nls.uk

[ix] Google Street View via google.co.uk/maps

[x] ‘I Remember When It Was Just Fields’ by Ron Brown published in 1983 by Milestone Publications, Portsmouth

[xi] image via www.ebay.co.uk

[xii] Warne’s Model Cookery, compiled and edited by Mary Jewry, published in London by Frederick Warne (undated; likely pre-1907 based on an owner’s inscription inside the cover).

[xiii] From the author’s personal collection

[xiv] From the author’s personal collection

[xv] The King Holds Hayling by FGS Thomas published by Pelham, Havant, 1961

[xvi] Full death certificate from GRO (pdf)

[xvii] From the author’s personal collection

[xviii] Full death certificate from GRO (pdf)

[xix] Full death certificate from GRO (pdf)

[xx] Full death certificate from GRO (pdf)