Click here to go back to the previous chapter

The coming of the First World War had a profound impact on Catherine, her family, and her business. Daughter Evelyn and her husband Harry Collingwood returned from Italy with their three children as growing tensions in Europe disrupted tourism and trade in Italy. But 1913 was a difficult year: in January, Catherine’s young grandson Reggie died of meningitis, and later that August, her husband Joseph died aged seventy-four from congestion of the lungs and kidneys, and cardiac failure.[i] Like most people at that time, they died at home, surrounded by family rather than in a hospital or care institution.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was customary for the blinds or curtains in the house were drawn immediately after a death and remain so until after the funeral. Cassell’s Household Guide advised that, in poorer households, female relatives might be better absent from the funeral if their emotions could “interrupt and destroy the solemnity of the ceremony with their sobs, and even by fainting”. [ii] However, Catherine’s husband’s funeral was notable for being the first held on Hayling Island with full military honours. Newspaper reports list male and female mourners, including his widow, surviving daughter, and two granddaughters, both under ten. [iii]

Mourning remained an important social ritual, especially for women. Black clothing signified respectability and grief, worn as soon as possible after a death. Widows and widowers were expected to observe a long period of formal mourning – often a full year in black, followed by months of more subdued grey or deep purple. Working families like Catherine’s, likely observed a simpler form of mourning, perhaps by dyeing existing garments black or wearing a black armband or bonnet.

Although mourning codes were easing by the twentieth century, the loss of so many close family members must have weighed heavily on Catherine’s later years. Before she was widowed, Joseph – previously an army paymaster – may have assisted with the financial side of the boarding house, keeping accounts and paying tradesmen and wages. After his death, Catherine assumed sole responsibility.

By the time Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, Catherine was sixty-four. Tourism and farming on Hayling Island were immediately affected: hundreds of horses were requisitioned for the army, young men enlisted by the thousand, and the Southern Command School of Musketry opened in the Royal Hotel. Essential goods became scarcer, while prices rose, and rail services – once a lifeline for holidaymakers -now carried troops and military supplies. Spare bedrooms and guest houses were taken over for military use, and Catherine likely found herself busy accommodating soldiers from across the Empire. The seasonal rhythms she had relied on for decades were upended by the constant stream of men from across the Empire, training with rifles and machine guns.

Electricity did not reach the island until the late 1920s, when only eighty-one houses were wired in anticipation[iv]. By then Catherine was in her late seventies, and it seems unlikely she adopted electric lighting or the labour-saving appliances of the interwar years, such as vacuum cleaners, electric sewing machines, or washing machines. Nevertheless, she may have welcomed smaller improvements: Sunlight Soap reduced the drudgery of laundry, Kerol disinfectant offered a safer way to clean floors and surfaces, and the hand-operated Ewbank carpet sweeper allowed quick tidying between guests. A wringing and mangling machine would have eased some of the back-breaking work on washday.

The Old Age Pensions Act of 1908 introduced means-tested pensions for those over seventy, paying up to five shillings per week for people earning less than £21 a year and nothing for those above £31 10s.[vi] When Catherine reached seventy in 1920, she was still running the boarding house as a going concern, and was unlikely to have qualified for a pension.

Catherine died peacefully at home in 1934, aged 84. Although no will has been found, she may have held a small burial insurance policy, as was common among the respectable working class. Weekly premiums of just a few pence would have provided the reassurance that her funeral expenses were covered without burdening her only surviving daughter and her family.

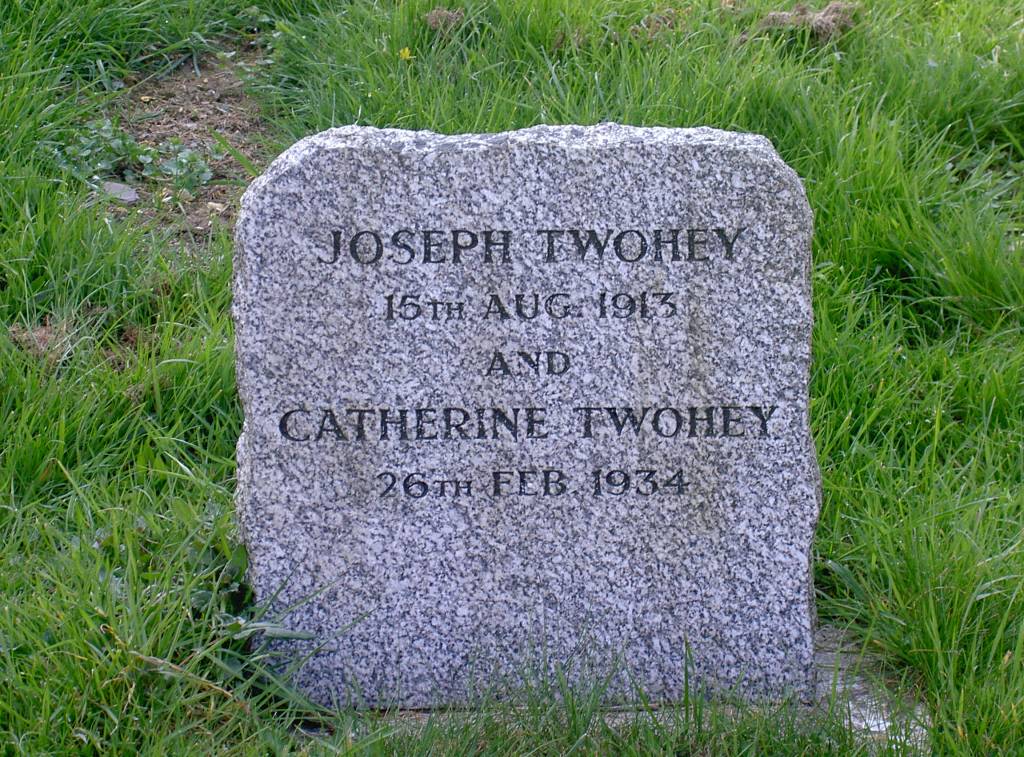

She was buried beside her husband in the churchyard of St Mary’s, South Hayling, and today rests close to the graves of her brother-in-law, two daughters, two granddaughters and their husbands, and her six-year-old grandson.

After her death in 1934, Osborne Cottage was advertised for vacant possession as a detached, double-fronted house with four bedrooms, two sitting rooms, a kitchen, scullery, and a large garden. It was to be let on a decontrolled tenancy at thirteen shillings per week, with the tenant paying rates.[viii] Interestingly, while the 1911 and 1921 censuses record eight rooms, the 1934 advertisement lists only seven, suggesting that one may have been repurposed, removed, or merged in the intervening years.

Catherine Dibben was a devoted daughter, loyal wife, caring mother, capable businesswoman, and dignified widow. At every stage of her life, she met change with courage and determination. What began for me as the tracing of a name became the rediscovery of a woman whose spirit endures – one life within the matryoshka of mothers and daughters.

[i] Full death certificate from GRO (pdf)

[ii] Cassell’s household guide to every department of practical life: being a complete encyclopaedia of domestic and social economy, published 1869 by Cassell, Petter, Galpin in London and New York via archive.org last accessed 7 Oct 2025

[iii] Various newspaper reports via findmypast.co.uk

[iv] ‘I Remember When It Was Just Fields’ by Ron Brown published in 1983 by Milestone Publications, Portsmouth

[v] From the author’s personal collection

[vi] Tracing Your Female Ancestors by Adèle Emm published 2019 by Pen & Sword, Yorkshire

[vii] From the author’s personal collection

[viii] Portsmouth Evening News – 23 March 1935 via findmypast.co.uk