Click here to go back to the previous chapter

Established at the onset of war in 1939, a network of around seventy five prisoner-of-war (POW) camps spread across Nazi-occupied Europe. These camps were highly organised operations, although a prisoner’s treatment often depended upon their nationality[i]. For most Western Allied prisoners, life was harsh but generally adhered to the Geneva Conventions. Able-bodied men held in Stalags (as opposed to officers, who were confined in separate camps known as Oflags), were expected to undertake work – often hard physical labour.

Stalag VIIIB, later renumbered Stalag 344, was one of the largest German POW camps during World War II. It was located near the small town of Lamsdorf (now Lambinowice) in Southern Poland, in what was then known as Upper Silesia. Between 1940 and 1945, it is estimated that more than 100,000 prisoners from a wide range of Allied nations passed through the camp. These included prisoners from Australia, Belgium, Britain, Canada, France, Greece, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Poland, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United States, and Yugoslavia.[ii].

At Arbeitskommando E72 – one of over sixty workcamps attached to Stalag VIIIB – the weeks of imprisonment and relentless toil in the Hohenzollern coalmine near Beuthen soon stretched into months. At last, Red Cross parcels began to arrive, bringing small but essential comforts such as food, tobacco, and hygiene items, and long-awaited letters that were lifelines to the outside world.

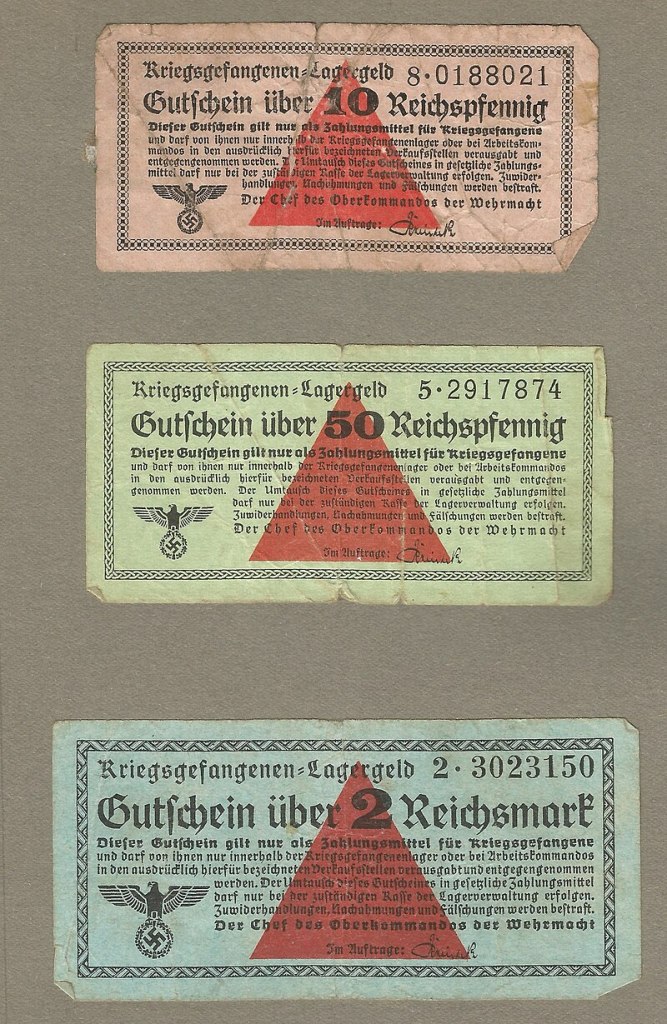

Within the camps, a system of currency known as ‘Kriegsgefangenen Lagergeld’ (prisoner-of-war camp money) was issued by the camp authorities to compensate prisoners for their work. These notes, each about the size of a cigarette or tea card, came in varying denominations, but had value only within the POW camps, rendering them useless for bribing guards. However, they allowed prisoners to buy small extras, such as food, from the camp canteen.

Gradually, most of the men began to adjust to the gruelling routine of their new existence, finding ways to hold onto the fragile belief that life, no matter how bleak, was still worth living.

Some may have come to terms with the fact that, had they not been captured, they would surely have died during the retreat of Dunkirk. Or, if they had made it home, would by now have been sent back to fight in one of the other theatres of war across the world.

E72’s location in what is now Bytom, Upper Silesia, in southern Poland, offered relatively safety compared to the dangers their families faced in Britain. The Luftwaffe’s relentless bombing campaigns – known as the Blitz – were devastating towns and cities across the UK. Between October 1940 and June 1941, tens of thousands of men, women, and children were killed, with countless more injured, or left homeless. Ted’s parents were among those affected when their family home in Kenneth Road, Fulham, was destroyed, along with neighbouring properties, by a high-explosive bomb[iv].

Despite thirteen-hour shifts in the mine, the prisoners were granted some leisure time in the evenings and on Sundays. Ted, assigned to the coal mine under his German captors, was able to put his skills as an electrician[v] to use. For this specialised work he received a little extra pay, which he could put towards some food or other necessities within the camp.

By this stage, malnutrition and disease remained a constant challenge, but boredom had become the prisoners’ greatest enemy. Memoirs by fellow prisoners recount the petty frictions that arose from prolonged confinement and the need for outlets to channel their frustration.

Everyday tasks such as cleaning latrines, washing and mending clothes, or writing the occasional letter home (although paper was strictly rationed, and every word carefully scrutinised by censors) offered only brief distractions. Letters were a vital lifeline, but the men knew they could not share any real details about their situation or hardships. Instead, they carefully crafted messages to reassure their loved ones while avoiding anything that might provoke the censors. Nevertheless, the monotony of long, dark winter evenings spent in the same company often became oppressive.

To help alleviate this tedium, by January 1942, the Red Cross and St John had sent over 40,000 books to camps and hospitals to set up libraries. They also provided packs of cards for bridge, cribbage, and other games, and draughts and chess sets[vi].

The camps, as microcosms of society, were filled with men with a wide array of skills and abilities. Committees were often formed to organise activities and make the most of these talents. Significant time and effort went into establishing club and societies to cater for various interests.

Surprisingly, the Germans not only permitted, but encouraged such activities. Perhaps they saw these pursuits as a “safety valve”, releasing tensions, improving morale, and maybe making their roles as captors a little easier.

Ted, already a talented pianist and guitarist[vii], became a regular member of the camp’s dance band, which performed on Saturday nights to German officers – hopefully earning a few extra Lagermarks in return.

At E72, the camp Commandant’s love of music[viii] allowed the band to flourish, eventually growing into a much larger orchestra. Musical instruments, vocal scores, and sheet music, were sent out to camps by the Red Cross and POW Department in London – and they even provided self-tutor manuals for banjos and ukuleles, inspiring a few budding George Formbys![ix]

Beyond music, the prisoners worked together to pass the time and enrich their lives by sharing their skills and knowledge. Men taught one another new crafts, languages, or practical skills that might prove useful after the war. For Ted, learning, playing, and performing music became a source of connection and purpose, and he also took the opportunity to practice and improve his German[x]. Over time, he and several other prisoners became fluent, a skill that earned them a degree of respect from their guards and likely made their lives a little easier.

Occasionally, group photographs were staged, either for propaganda purposes or as morale boosters, and these were often printed in the form of postcards. For these, prisoners were temporarily provided with clean clothing, and instructed to smile for the camera, creating the illusion that they were well-dressed, content, and seeming well-treated. In the photograph below, the sitters appear slightly ill-at-ease, giving the image an unsettling, surreal quality.

Another photograph, taken on the same spot – likely on the same day, based upon the appearance of the tree in the background – shows the men looking more relaxed and comfortable despite the formal setup. The chalkboard caption, “Cockneys Roll on London”, suggests this group may have been composed from men from the London area.

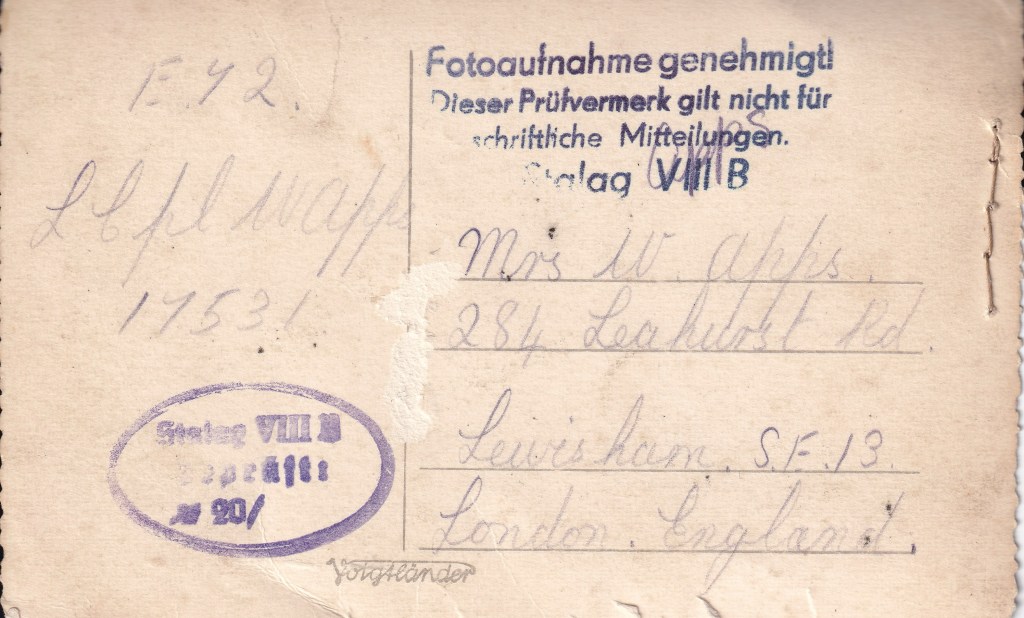

Lance Corporal Wilfred Charles Apps, known in the camp as Wally[xi], is the tall man 5th from the right in the back row of the photograph. He sent this as a postcard to his wife in Lewisham, and later passed it on to Ted’s family.

All POW mail was closely monitored, and the rubber stamp on the back of this postcard at the top right indicates that the image was inspected and approved by camp officials for mailing. “Fotoaufnahme genehmigt” translates as ‘Photograph approved’, and “Dieser Prüfvermerk gilt nicht für schriftliche Mitteilungen” means ‘This approval does not apply to written messages’.

As such, L/Cpl Apps was only permitted to include his rank, name, POW number, and camp details as his message. Even this minimal information was subject to censorship, as indicated by the oval stamp on the left, which confirms the postcard’s approval by German authorities before being sent to the recipient in England.

When Mrs. Apps received the postcard, the familiar handwriting and photograph would have at least given her a little reassurance that her husband was still alive and safe, albeit unable to communicate any further.

Time ticked by and the men at E72 settled into a kind of routine. Despite the hardships, they had manged to create a semblance of normality – building friendships, organising activities, and enduring the monotony of camp life.

But, after four and a half years in captivity, their fragile stability was shattered on the evening of Friday 19th January 1945 when camp officers delivered unexpected orders: the prisoners were to pack their belongings and be ready to leave by 6 a.m. the following morning.

For some, the prospect of change may have sparked cautious optimism and, perhaps, they dared to hope that liberation was near.

But the reality was far darker. With Russian forces advancing rapidly from the east, the Germans had no intention of letting their prisoners to fall into enemy hands. Instead, they planned to march the men westward, deeper into German territory – towards Berlin – where they would serve as human shields against the Allied onslaught.

Ted and his comrades could not have imagined the ordeal that lay ahead. The gruelling journey that they would embark on the next morning would later become known as The Long March – a test of endurance and survival that would haunt those who lived through it.

Click here to read the next chapter…

By an extraordinary twist of fate, in the 1970s, Ted Mayhew’s son, Barry, was working for a company in Ashford, Kent. During a casual conversation with a colleague, Barry discovered that this colleague was none other than L/Cpl Apps, now known as Bill, the man who had spent nearly five years as a POW alongside his father. A couple of days later, Bill brought in the wartime postcard he had sent to his wife, passing it on to Barry so he could share it with Ted[xii].

The phrase – and title of this blog – ‘Funny Where Life Takes You’ perfectly sums up how a chance meeting and a simple postcard reconnected two families after over fifty years. It just goes to show how unexpected paths can lead to extraordinary discoveries.

[i] https://portal.ehri-project.eu last accessed 04/12/2024

[ii] www.prisonersofwarmuseum.com last accessed 05/12/2024

[iii] By CharlesC – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63721470, last accessed 04/12/2024

[iv] http://www.bombsight.org, last accessed 04/12/2024

[v] Letter from Ted’s friend Johnny Butler in the personal collection of Pauline Weir

[vi] Prisoner of War News 1 Jan 1942 via www.findmypast.co.uk last accessed 4 Dec 2024

[vii] Family oral history as recalled by Pauline Weir, 4 Dec 2024.

[viii] New Zealand POW magazine article about Colin Bisset, violinist, via email from John West Apr 2024

[ix] The Soldier Who Came Back by Steve Foster with Alan Clark, published by Mirror Books, 2018

[x] Letter from Ted’s friend Johnny Butler in the personal collection of Pauline Weir

[xi] Many of the face in the postcard were remembered in the 1990s by George Hawkins, who annotated a copy of the photograph, now in the possession of his daughter Christine Parry Jun 2024

[xii] Family oral history as recalled by Pauline Weir, 4 Dec 2024