Click here to go back to the previous chapter

Warning: some readers may find aspects of this story distressing.

This is the third chapter in the story of Ted Mayhew, one of the many British soldiers not rescued during the celebrated Dunkirk evacuation in June 1940. While 300,000 men were successfully evacuated, an estimated 68,000 British soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured. Of these, around 40,000 were left behind and taken prisoner by the advancing German forces.

Twenty-one-year-old Ted Mayhew was among those captured, and for months his parents were left in anguish, unsure if their only son was alive or dead.

In the weeks following Dunkirk, Britain found itself vulnerable, having lost significant equipment during the evacuation. Hitler sought to force a surrender by gaining air superiority over Britain, leading to the beginning of the Battle of Britain—a pivotal air campaign fought entirely in the skies. The Royal Air Force (RAF) successfully defended the UK against large-scale attacks by the German Luftwaffe.

Germany had many pilots but lacked planes, while Britain had few of both. However, Britain held a crucial advantage: radar. This, combined with the German decision to switch from targeting airfields and factories to attacking major cities, allowed the RAF to claim a narrow but significant victory. At great human cost, Britain maintained air superiority and indefinitely postponed a German invasion[i].

Meanwhile, Ted’s official status remained “Missing in Action,” although he had actually been taken prisoner and transferred to the notorious Stalag VIIIB prison camp in Lamsdorf, Silesia (now Lambinowice, Poland). But, by the time his parents finally received a communication from the Red Cross confirming that Ted was alive but a Prisoner of War (POW), he had already been moved on elsewhere.

The reverse of Ted’s Personalkarte (personnel record) reveals that he was inoculated for typhus on 2nd September 1940. Typhus is a severe and dangerous infectious disease transmitted by fleas, lice, and mites. Although Ted and his fellow prisoners had their heads shaved and were deloused upon arrival, the combination of poor sanitation and overcrowding allowed fleas and lice to thrive, feeding on the mice and rats that infested the camp. The same Personalkarte also records that Ted was transferred on 20th September 1940 to “Hohenzollerngrube: Beuthen E72”[ii].

Although the Geneva Convention of 1929[iii] stipulated that prisoners of war should not be forced into dangerous or war-related labour, many POWs died due to extreme mistreatment and malnutrition. Ted was likely taken by train with other POWs to the town of Beuthen (now Bytom) in occupied Poland. He, and around a hundred other prisoners, were housed in a disused ‘Biergarten’ (beer garden) with a small building repurposed as a barracks for the E72 Arbeitskommando (work camp) [iv]. For the next four years, Ted worked as part of a forced labour party in the nearby Hohenzollern Coal Mine.

This coal mine was one of many industrial sites where Allied prisoners endured harsh conditions and dangerous labour, contributing to the German war effort. Contemporary accounts from other POWs describe long hours in perilous underground environments, poor treatment, and inadequate medical care.

Historic photographs reveal the grim setting, dominated by a 17-meter hoist tower built in the 1920s to replace the old steam engines with electric ones.

Like many survivors of the war, Ted rarely spoke of his experiences. In an era before PTSD was widely understood, it’s possible he wished to leave those memories behind, sparing his loved ones the burden of his past. Coal was the lifeblood of the German war economy, powering the armaments, chemical, and power industries, as well as the railways and private households. To maintain these supplies, hundreds of thousands of foreign civilian workers and POWs were forced into gruelling labour in the coal mines.

The men worked a 13-day shift, with one Sunday off every two weeks, cleaning their clothes in the shower on the final day of their shift. Pte George Hawkins, a fellow POW recalled: ‘There were rats down the mine but no gas. It had electricity throughout and bright lights. Seams were 18m deep, dug out in three layers, and then filled with sand. They [POWs] were told never to try and hide in the pit, pumps were working all the time or it would flood within 24hrs. Miners would always warn ‘vorsichtig’ –take care, and would listen for sounds of collapse. No one died in the mine, or at the camp, only in the hospital. During the winter the POWs were often pleased to go down the mine out of the cold.”[v]

Ted’s daughter recalls one story he shared: his life was saved by an experienced Polish miner, who noticed water leaking from the mine shaft and heard the ominous sound of rocks shifting. He shouted at Ted to get out—just moments before the roof collapsed.

The weather during their first winter in Beuthen was likely colder than any of the men had ever experienced. With temperatures dropping to -23°C and heavy snowfall, even a short trip to the latrine—just a few metres away—was a daunting prospect. The latrine consisted of a five-hole bench over an open cesspit, which soon froze solid in the bitter cold. New waste piled on top of the ice, forming cone-shaped masses that rose higher and higher. Eventually, a guard had to go to the village to fetch a stout piece of timber, which the men used to tip over the frozen cones and roll them to the back of the cesspit[vi].

When not on shift in the mine, the men were sometimes forced—at bayonet point—to shovel snow from the railway line. However, when they were able to return to the billet, the iron stove in a corner of the hall had done little to warm the interior of the building, and the two thin blankets on the bare boards of their wooden bunks offered little in the way of comfort.

(click on image to open full size)

The International Red Cross played a vital role in supporting POWs during this time. They coordinated the exchange of information between POW camps and the prisoners’ families, compiling lists of captured soldiers and ensuring their families were informed of their location and how relatives could write to them and send parcels[vii]

Meantime, the Red Cross organised the delivery of parcels containing food, clothing, and medical supplies to prisoners. These parcels, often the difference between survival and starvation, were a lifeline for many POWs, providing essential nutrition and a morale boost.

However, six months after their capture, very few men in E72 had received any letters from home. Those who had been registered as POWs soon after capture in France were more fortunate, but the rest, including Ted, were registered much later so their families waited far longer to learn of their fate. By the time letters began to trickle through, a backlog of 70,000 letters was still waiting to be censored at Lamsdorf[viii]. Some men had to wait over nine months to hear anything from their loved ones. Those who did receive letters shared news of the heavy bombing during the Blitz, but this only heightened the anxiety of those still waiting for word from home[ix].

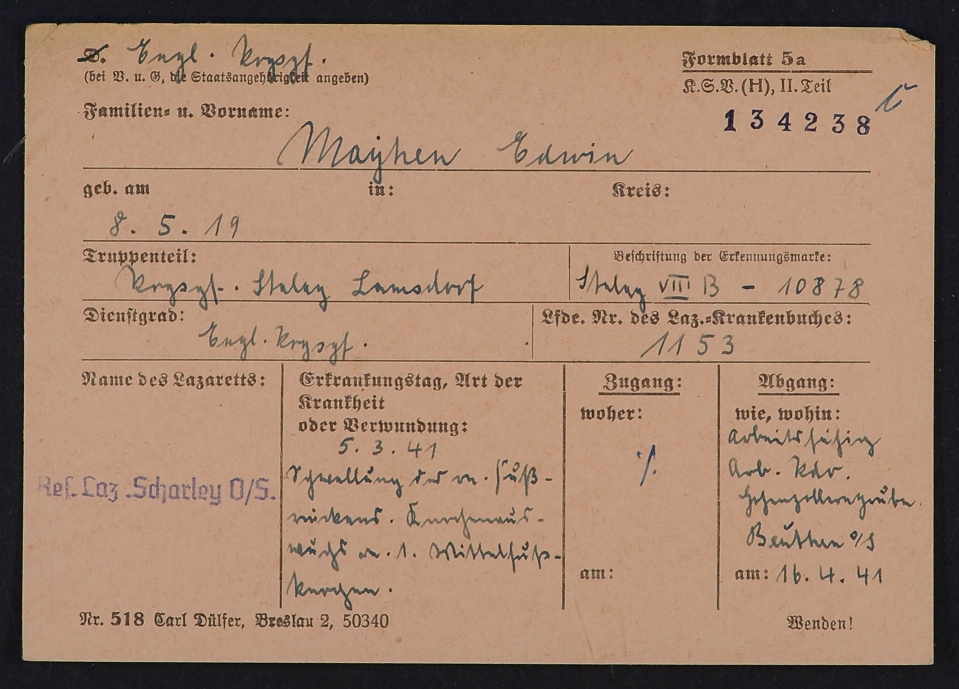

The strain of forced labour, harsh living conditions, and lack of proper nutrition undoubtedly took a toll on the men’s health. Ted, like many others, faced not only the emotional burden of delayed communication from home but also the physical hardships of his imprisonment. His Personalkarte reveals that he was admitted to Lazarett Scharley, the camp hospital back at Stalag VIIIB, on 5th March 1941 for what appears to have been an abscess on the middle bone of his right foot. While the cause of the injury is not specified, it was most likely work-related.

The hospital facilities at Stalag VIIIB were among the best in the German camps. The Lazarett was located on a separate site, comprising eleven concrete buildings. Six of these were self-contained wards, each accommodating around 100 patients. The remaining buildings housed treatment blocks with operating theatres, X-ray and laboratory facilities, kitchens, a morgue, and accommodations for medical staff.

Although the hospital was headed by a German officer with the title Oberst Arzt (‘Colonel Doctor’), the medical staff were entirely POWs. Among them were general physicians, surgeons, a neurosurgeon, psychiatrist, anaesthesiologist, and radiologist.

Ted’s condition must have been quite serious, as he was not discharged until 16th April 1941, more than a month later. However, he seems to have made a full recovery with no lasting effects, returning to the beer hall billet at Beuthen.

Once lines of communication were established by the Red Cross, POWs were permitted to send one postcard each week. Occasionally, the Red Cross also organised group photographs, printed as postcards, allowing the men to send a visual message to their families, offering much-needed reassurance that they were still alive. Some of these photographs have survived, including the one below, which shows Ted third from the left in the middle row, and Eric West on the far right[xii].

(click on the image to view full size)

What is striking about this image and other similar photographs is how clean and well-presented the prisoners appear, their uniforms and boots spotless, and their demeanour surprisingly relaxed. It is believed that such images were carefully staged to impress Red Cross inspectors and conceal the harsh realities of life in the camp. Adding to this illusion of normality, the British Red Cross published an official journal, The Prisoner of War, which was sent free of charge to the next of kin of POWs, offering a more optimistic portrayal of camp life[xiii].

However, the reality at E72 was far darker. Documents in the National Archives reveal accounts of war crimes and the mistreatment of prisoners, reportedly sanctioned by the camp commandant, Unterfeldwebel Johann Engelkircher[xiv]. Known to the POWs as ‘John the Bastard‘[xv], Engelkircher was described by survivors as a committed Nazi who ruled the camp with cruelty.

Ted himself bore lifelong reminders of this brutality. A 2.5cm (1in) scar across his forehead, just below the hairline which marked an incident when a guard struck him with a rifle butt, an injury he later recounted to his family[xvi]. On another occasion, a guard fired a Luger pistol next to his head, rupturing his eardrum and leaving him permanently deaf in one ear[xvii].

During their time at the E72 Arbeitskommando, four British prisoners died and were buried at the cemetery in Schomberg, near Beuthen.

Engelkircher was widely believed to have been responsible for the deaths of three British and two Palestinian POWs, his reputation for cruelty well known amongst the prisoners. Yet, after the war, Engelkircher vanished and was never brought to justice. In contrast, Gerhard Spaniol , the mine’s civilian foreman, faced trial for war crimes and was sentenced to seven years in prison in September 1947, although his sentence was ultimately revoked in December 1951[xviii].

Despite the bleak environment and Engelkircher’s cruelty, Ted and his fellow prisoners gradually adapted, showing remarkable resilience and resourcefulness to cope with the harsh conditions they faced.

Click here to read the next chapter…

With grateful thanks to John West and his excellent website 140th (5th London) Army Field Regiment, Royal Artillery. John’s father Eric West and Ted Mayhew were POWs together at E72 and they appear together in several photographs.

[i] www.bbc.co.uk > History > World Wars > World War II: Summary of Key Events last accessed 7 Sep 2024

[ii] The National Archives (TNA) Ref WO 416/251/231

[iii] https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/1d2cfc/pdf/ Geneva Convention 1929, Chapter 2-3, Articles 27 to 34, last accessed 21 Oct 2024

[iv] E72 camp interpreter 1940-1944 Norman Gibbs’ Imperial War Museum interview forwarded by John West creator of http://140th-field-regiment-ra-1940.co.uk

[v] British Soldiers become Coal Miners via http://140th-field-regiment-ra-1940.co.uk last accessed 23 Oct 2024; original source https://www.prisonersofwarmuseum.com/working-parties/e72-beuthen/ confirmed by Christine Parry 30 Oct 2024.

[vi] Ibid

[vii] C.C.D Brammall – Sunday Mail 22 Jun 1941 via https://wartimememoriesproject.com last accessed 23 Oct 2024

[viii] Ibid

[ix] Ibid

[x] The National Archives (TNA) Ref WO 416/251/231

[xi] Ibid

[xii] Eric West and Ted Mayhew were POWs together at E72 and they appear together in several photographs.

[xiii] https://www.prisonersofwarmuseum.com/the-prisoner-of-war-magazine/ last accessed 23 Oct 2024

[xiv] The National Archive (TNA) Ref WO 309/22

[xv] War Crimes and Captivity via http://140th-field-regiment-ra-1940.co.uk/ last accessed 21 Oct 2024

[xvi] Conversations with Ted’s daughter Pauline Weir 2024

[xvii] Ibid

[xviii] Arthur Engleskirche and Gerhard Spaniol via http://140th-field-regiment-ra-1940.co.uk last accessed 23 Oct 2024