While preparing material recently for an art exhibition celebrating the 111th anniversary of the ‘Great Pilgrimage’, I was reminded of the incredible history of women who campaigned for the right to vote. The Great Pilgrimage took place in the summer of 1913, when thousands of women marched, rode horseback, or cycled from various points across England and Wales to London, gathering for a peaceful rally in Hyde Park. The rally drew over 50,000 people, advocating for women’s suffrage. You can find out more about the 111 Years Forward project here.

During my research into historical suffrage posters and postcards, a personal connection surfaced: a key figure in the peaceful suffragist campaign, who later became my cousin’s grandmother. As children, my brother and I visited her at Wyke Lodge, her home near our own grandmother’s house in Wyke Regis, Dorset.

This remarkable woman was Catharine Courtauld, who was born in Bocking, Essex on 25 May 1878[i], the fourth of six children born into a wealthy family descended from Huguenot refugees who first came to Britain in the early eighteenth century. Catharine’s ancestors, originally gold and silver smiths, who had later turned their hand to the silk trade, providing much needed employment to the weavers of East Anglia left in poverty after their traditional woollen cloth trade had moved to the north of England. The Courtauld family made their fortune producing black silk crepe which was worn by the Victorians during their lengthy periods of mourning[ii].

Even before Catharine was born, her family was active in the women’s suffrage movement. The first mass suffrage petition of 1866, seen as the movement’s beginning, had been signed by members of the Courtauld family.[iii] Catharine’s older sister Sydney Renée later recalled their upbringing, noting their family’s non-conformity, particularly their Unitarian beliefs, and their mother’s artistic influence[iv]. Their cousin and fellow suffragist, Katherine Mina Courtauld, was a farmer and advocate for agricultural training for women, who famously spoiled her 1911 census return in protest, and lived openly with her female partner for over 50 years[v].

When Catharine’s parents died (her father in 1899 and her mother in 1906), she and Sydney Renée inherited a large fortune[vi], which, combined with their progressive upbringing, led them to join the London Society for Women’s Suffrage. Although the Liberals had promised to support Women’s Suffrage in the 1906 General Election – and won a landslide victory – hopes were dashed two years later when Herbert Asquith, a staunch opponent, became prime minister.

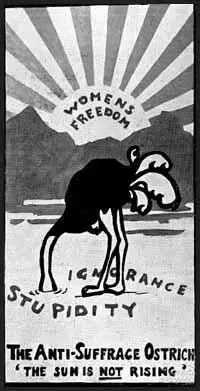

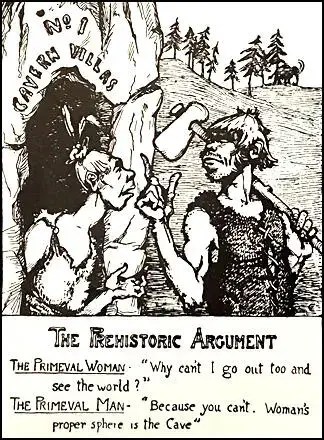

Catharine and her sister were suffragists – supporting law-abiding activism, unlike the more militant suffragettes led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters. An accomplished sculptor and artist, Catharine was one of the founding members of the Suffrage Atelier, formed in early 1909 to produce propaganda material. Whilst she continued to use her wealth to support social reform through community hospitals, educational trusts and charitable funds[viii], Catharine soon became one of the Suffrage Atelier’s most active members. Her contributions included some eye-catching posters and postcards, often tinged with humour, challenging anti-suffragist arguments including The Anti-Suffrage Ostrich (c.1909) and The Prehistoric Argument (1912)[ix], along with others which are held today in the Museum of London collection.

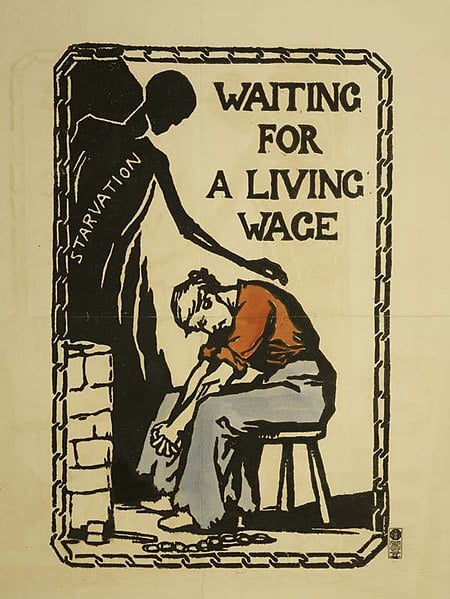

The Courtauld family’s success was rooted in their care for workers, and Catharine’s poster Waiting for a Living Wage (c.1913) captured the harsh realities for working women. The poster shows a weary woman approached by the spectre of starvation, highlighting the connection between voting rights and improving women’s working conditions.

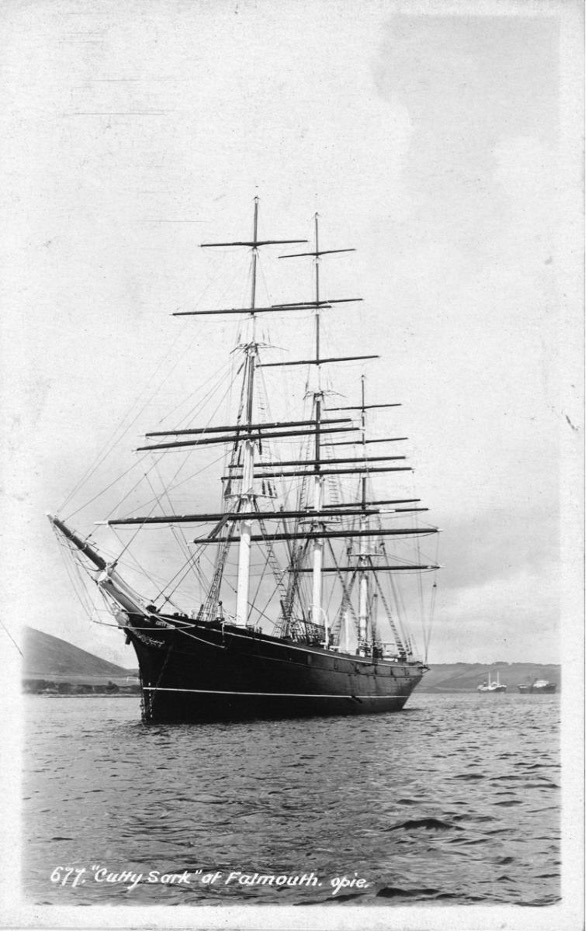

In 1912, Catharine embarked upon a three-month sea voyage aboard the cadet training ship Port Jackson. She and her sister Sydney Renée were two of just three passengers, alongside a crew of thirty four and twenty four cadets[x]. On the voyage, Catharine and the ship’s Mate, Wilfred Dowman, fell madly in love – despite the complication that he was already married with two children. Nevertheless, back on shore, he and Catharine soon set up home together and lived together for several years. In 1918, Catharine changed her name from ‘Courtauld’ to ‘Dowman’ by Deed Poll, prompting the first Mrs Dowman to initiate divorce proceedings[xi].

It was a messy divorce, and the marriage was finally dissolved in November 1920. Eleven days later, Wilfred and Catharine were married in London[xii].

The couple had two children, Colin Kenneth, born in 1920 before the divorce was finalised, and Margaret Renée in 1923. They settled in Falmouth, Cornwall, where Wilfred operated the training ship Lady of Avenel[xiii] offering ‘poor boys of good character’[xiv] two years of practical training under experienced instructors, along with food, a uniform, and pocket money[xv].

However, fate took a dramatic turn when a storm-damaged Portuguese sailing ship, Ferreira, limped into Falmouth for repairs. Wilfred immediately recognised her as Cutty Sark, the legendary British clipper he had admired as a young apprentice. Built in 1869, Cutty Sark had set records for speed, but her glory days were behind her, and she had fallen into disrepair.

Wilfred – not a man who let his head rule his heart – was determined to save her despite the formidable financial challenges. His initial attempts to purchase the ship were unsuccessful, and he likely watched with heavy heart as she sailed out of Falmouth in March 1922. Less than three months later, she was sold to another Portuguese owner and renamed Maria do Amparo[xvi].

Nevertheless, Wilfred persevered. He made a significantly higher offer to her new owner – far more than her commercial value – and, in October 1922, Cutty Sark returned to Falmouth under tow, ending her service under sail and reclaiming her original name[xvii].

Though Captain Dowman was listed by Lloyds Register as her sole owner[xviii], it was Catharine who had financed the purchase by selling a considerable portion of her inheritance[xix].

With Cutty Sark’s future now assured, Wilfred’s pride and joy was lovingly restored in Falmouth to her full-rigged glory. To help cover costs, Lady of Avenel was sold, and in 1924, once restoration was complete, Cutty Sark was proudly displayed as the flagship at the Fowey Regatta[xx].

For sixteen years, Cutty Sark was moored in Falmouth, serving as a training ship for naval cadets, offering them practical, hands-on instruction in seamanship. She also became the first historic ship open to visitors since Francis Drake’s Golden Hind was exhibited off Deptford in 1580[xxii].

In 1934, the Dowmans moved to Wyke Regis, but sadly Wilfred died suddenly of a cerebral haemorrhage whilst at sea in the mid-Atlantic two years later. After his death, his widow determined that Cutty Sark should continue to be used for training and ‘sold’ her to the Thames Nautical Training College for a nominal sum of ten shillings. The ship was towed to Greenhithe, Kent, and Mrs Dowman also generously donated £5,000 for her future upkeep[xxiii].

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the cadets were evacuated, and Cutty Sark was left unmaintained. By the war’s end, sail training had fallen out of favour, leaving the once-cherished vessel’s future in jeopardy.

Fate intervened once again when HMS Implacable, a ship that had fought at the Battle of Trafalgar, was considered for preservation in Greenwich. However, due to the high costs of restoration, she was instead scuttled off the Isle of Wight. It was then that Frank Carr, Director of the London Maritime Museum, convinced the then Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Philip, a fellow seafaring man, of the importance of preserving Cutty Sark. Together they formed a society that raised public funds to restore the ship and build a new dry dock for it in Greenwich[xxiv].

Three years later, in 1957, after extensive restoration, Cutty Sark was opened to the public by HM Queen Elizabeth II, with Mrs Dowman present at the ceremony.

Catharine Dowman spent the remainder of her life in Wyke Regis, where she was very active in the community and supported many local causes. During the Second World War, she served as a member of the WRVS helping to keep civilians safe from air raids, and later gifted land and a boat to the local scout group[xxv]. Writing under the androgynous name C. Dowman, she also wrote and illustrated a delightful children’s book, Sam and the Others, which entertained my brother and me as children. I still have the copy she gave us, inscribed with a loving message in her handwriting.

Known affectionately as ‘Granny Cath’ to her family, I remember Mrs Dowman as a gentle and charming lady with a mischievous twinkle in her eye. Her home was filled with wonders, including some Victorian toys that she would let us play with, and treasures from her travels around the world.

She continued to take a keen interest in Cutty Sark and made her last visit to the ship in 1968, at the age of ninety. Catharine Dowman (née Courtauld) died four years later, but her legacy of unconventionality, determination, and generosity continues to be remembered to this day.

[ii] Oxford Dictionary of National Biography via https://www.oxforddnb.com last accessed 18 Oct 2024

[iii] Braintree Museum exhibition 2020

[iv] Master Mariner’s Mirror p 458 last accessed 3 Sep 2009

[v] Oxford Dictionary of National Biography via https://www.oxforddnb.com last accessed 18 Oct 2024

[vi] Master Mariner’s Mirror p 458 last accessed 3 Sep 2009

[vii] image ©Amersham Museum via https://amershammuseum.org

[viii] https://spartacus-educational.com > Catharine Courtauld last accessed 16 Oct 2024

[ix] Ibid

[x] Master Mariner’s Mirror p 458 last accessed 3 Sep 2009

[xi] The National Archives Ref. J18/261

[xii] Master Mariner’s Mirror p 458 last accessed 3 Sep 2009

[xiii] https://en.wikipedia.org > Cutty Sark last accessed 18 Oct 2024

[xiv] Master Mariner’s Mirror p 458 last accessed 3 Sep 2009

[xv] Ibid

[xvi] Ibid

[xvii] Master Mariner’s Mirror p 458 last accessed 3 Sep 2009

[xviii] Ibid

[xix] Royal Museums Greenwich via https://www.rmg.co.uk

[xx] Ibid

[xxi] image © Royal Museums Greenwich via https://www.rmg.co.uk

[xxii] Royal Museums Greenwich via https://www.rmg.co.uk

[xxiii] Ibid

[xxiv] Ibid

[xxv] Master Mariner’s Mirror p 458 last accessed 3 Sep 2009

[xxvi] image © Royal Museums Greenwich via https://www.rmg.co.uk