Click here to go back to the previous chapter

Warning: some readers may find aspects of this story distressing.

Seven months earlier, Ted Mayhew had been a young electrical engineer from Fulham with a bright future with London Transport. He’d left that life behind to become Private Mayhew, 945507, part of the British effort to stand up to Hitler and bring peace to Europe.

We don’t know if Ted was alone or with comrades when he was captured but, from that moment, he was stripped of his dignity and forced into total subjugation by his captors joining over 100,000 soldiers of the British Armed Forces captured during the Second World War and ultimately placed in prisoner of war camps[i].

Ted was probably in a state of shock as heavily armed German soldiers rounded him up, shouting and gesticulating for him to raise his hands. Whether alone or with others, he was likely taken to a nearby building, perhaps a church or school, which had been commandeered as a makeshift prison.

Contemporary accounts describe the noise and confusion, with hundreds of people crammed into these improvised holding areas. Conditions were desperately overcrowded, with minimal facilities and basic provisions. Wounded men were everywhere – some on stretchers, others sitting or lying on the ground. Their uninjured fellow captives often tried to help wherever they could, by holding bloody dressings, offering cigarettes, or just speaking words of comfort.

Amidst the chaos, Ted might have realised that he had surrendered to an enemy utterly overwhelmed with the sheer number of prisoners in their control, with no resources to manage them. He might have felt a mixture of fear, anger, and humiliation, and perhaps a grim sense of relief at having surviving whilst so many around him had been killed or terribly injured. Disbelief and frustration would have set in, compounded by concern for his comrades and uncertainty about his future. Over the next few hours or days, Ted and his fellow detainees were kept under armed guard, and possibly subjected to initial interrogations.

It was not until two months later that his parents received a telegram informing them that their son, 945507 Gnr E.G.A. Mayhew of the 140th Army Field Regiment, was ‘Missing in Action’ since a date unknown[ii].

Within days of his capture, it seems likely that Ted and other prisoners was transferred to a more organised transport camp. The journey was traumatic, with little food, water, or access to sanitary facilities. Guards were vigilant, and the prisoners endured harsh treatment.

Survivors later described[iii] being forced to march many miles each day, and occasionally transported on rickety old open lorries. They rarely had any shelter – by day they were baked in the summer sun, and by night they froze in open fields as they crossed Belgium towards the border with the Third Reich.

No rations or drinking water were provided, and their only sleeping accommodation was the ground where they stopped for the night. Toilets were non-existent, and many men grew weak and debilitated as their stomachs reacted to the stagnant water they were forced to drink from ponds or brooks along the way.

The groups of prisoners grew as more men joined them on the route, forming pitiful columns that stretched endlessly across the countryside. Occasionally, civilians along the way tried to help by throwing bread to the prisoners or leaving buckets of water, but German guards often kicked the buckets over, spilling the water on the ground. These simple acts of kindness came at great risk, as the guards could respond with beatings, whippings, or even executions on the spot.

The guards overseeing these marches were often young men who had grown up in 1930s Germany, a time marked by economic hardship and the pervasive influence of Nazi ideology. Many had been deeply indoctrinated, vilifying their perceived ‘enemies’ as subhuman and glorifying brutality as a necessary tool for the survival of the Reich. The harshness of their actions reflected the propaganda that had surrounded them and stemmed from a combination of fear, the pressure to conform, and a deep-seated belief in the superiority of their cause. For some, the brutality was a means of asserting power and control in a world that had offered them little stability or hope.

Eventually, Ted and the others reached a railway station where they were herded at gunpoint into cattle trucks. These trucks had no windows, only a few narrow slits about 50mm high (about 2in) and 300mm wide (about 12in) so there was no ventilation, and the air quickly became stale and stinking.

Men were packed so tightly they could only stand or sit with their knees tightly drawn to their chest on filthy straw soiled by previous human or livestock cargo. Some were already ill with fever or dysentery, but there was no toilet – not even a bucket. A few soldiers who still had steel helmets ripped out the linings and resorted to using the helmet as a chamber pot, then disposing of the contents in any way they could through cracks or holes in the floor. However, some could not get a helmet in time and simply lost control of their bowels where they stood.

There was no fresh water for drinking or washing on the trains and the dehumanisation had begun. Nearly 100 years on, many of us are familiar with harrowing documentary images of the transportation of Jewish people and others to concentration camps, but these same trains were also used to carry prisoners of war, often along the same lines right across Germany and over the border to newly occupied Poland.

By the time they crossed the Polish border, Ted might have felt a mix of resignation and anxiety, with occasional glimmers of hope fuelled by rumours of prisoner exchanges or better conditions at permanent camps. Nevertheless, he and his fellow captives faced profound uncertainty about their ultimate destination, and the length of their captivity.

At last, on 14th June 1940, two weeks after his initial capture and following a gruelling journey of nearly 1,300km (800 miles), Ted arrived at Stalag VIIIB in Lamsdorf, Silesia (now Lambinowice, Poland). Another prisoner described the scene ‘‘We entered Lamsdorf through double gates over which was plaited an arch of barbed wire. The flat land of the camp was well defined by strong wooden posts supporting well laced barbed wire at least seven feet high. The weather was extremely hot, and we needed to stand in queues to receive our ration of boiled potatoes, in their jackets and gritty, and soup. We were put in new barracks and registered as prisoners of war.”[iv]

The camp had originally been created to hold around 3,000 French POWs during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. During the First World War, the site was greatly expanded with some 90,000 prisoners interned there. By the time Ted reached the gates of Stalag VIIIB, he was just one of thousands arriving daily.

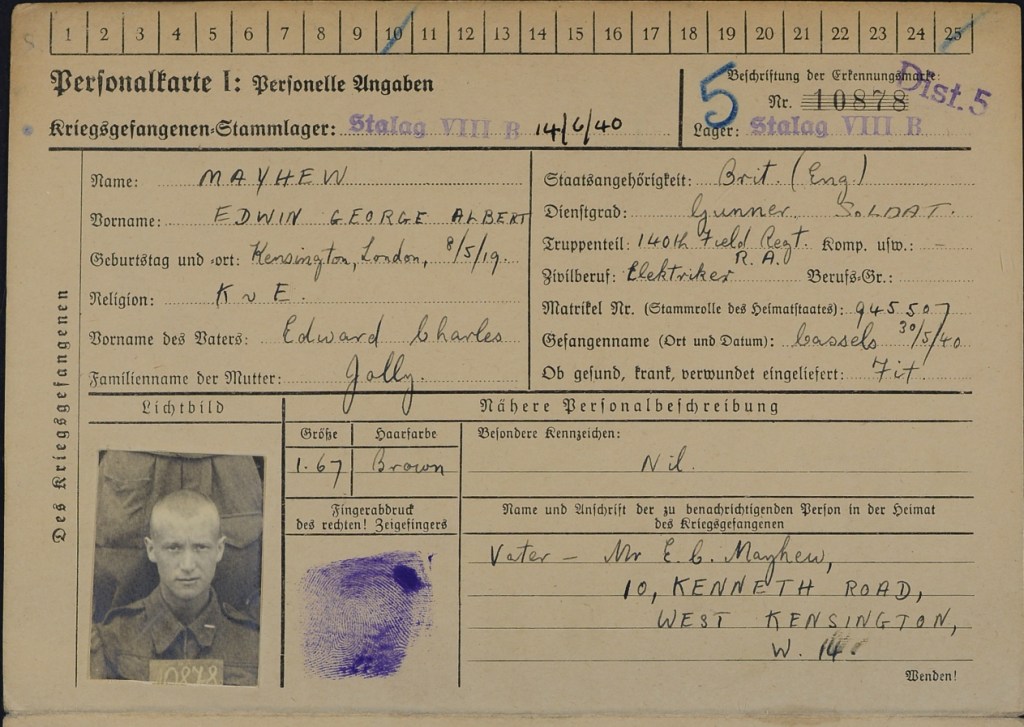

Each new arrival was body searched and lined up. One by one they were processed and issued with a POW number, which would be used for all official purposes during their captivity. Ted became 10878 and was issued with an identity tag to be worn with his British army tags. He was hosed down, his head shaved, and his photograph taken for his prison record.

In later life, his daughter recalled that he bore his POW number as a tattoo on his left forearm. However, the practice of tattooing identification numbers is primarily associated with Nazi concentration camps. While it is not impossible that this was done by his captors, it’s more likely that Ted and his fellow POWs later chose to tattoo their POW numbers on themselves as a form of solidarity, identity, or resistance.

Despite being instructed to provide only his name, rank, and serial number if captured, Ted was compelled to fill out a Personalkarte, or ‘capture card’[v]. The card was printed in old-style German and completed in English in Ted’s own handwriting. It contains extensive details, including his photograph and fingerprint. Though he may have been coerced into completing this form, he was not alone; the National Archives at Kew today holds an estimated 190,000 records of individuals captured in German-occupied territory during the Second World War. This collection includes primarily British servicemen, along with Canadians, South Africans, Australians, and New Zealanders, as well as several hundred British and Allied civilians, and a few nurses[vi].

Ted’s Personalkarte (personnel record) documenting his arrival at Stalag VIIIB, Lamsdorf, is dated 14th June 1940. It was another five months after his capture that his name was included on a list of Prisoners of War (Previously Reported as Missing) compiled by the War Office for the period 10th September to 1st October 1940[viii].

Some days later, his parents would have received a telegram informing them their only son was alive but had been taken prisoner. However, by the time they received this bittersweet news, Ted was no longer at Stalag VIIIB. He had already been transferred to an Arbeitskommando, a work detail outside the main camp, where he was put to work in the harsh conditions underground at a coal mine in Beuthen (now Bytom in Poland).

The uncertainty and fear that had no doubt gripped his parents during the weeks he was missing were now replaced by a different kind of worry as they realised Ted’s ordeal was far from over. Meanwhile, they too were enduring their own trauma, as London was in the grip of the Blitz, with thousands of bombs raining down on the capital almost nightly. Although Ted would eventually make it back, he would never see the house he grew up in again – Kenneth Road was destroyed by a high-explosive bomb during that terrifying time[ix].

Click here to read the next chapter

[i] www.ancestry.co.uk About UK Prisoners of War, 1939-1945 last accessed 1 Sep 2024

[ii] National Archive > Army Casualty Lists 1939-1945 Re. WO 417/15 last accessed 1 Sep 2024

[iii] Sources include The Soldier Who Came Back by Steve Foster with Alan Clark published by Mirror Books, 2014, Survivor of the Long March by Charles Waite, published by Spellmount in 2021, The Long Way Home by John McCallum, published in Oxford by ISIS in 2006, and

[iv] Norman Gibbs’ war memories, donated to the Bytom Museum in Poland, near to the site of his captivity in Silesia, via http://140th-field-regiment-ra-1940.co.uk last accessed 3 Sep 2024

[v] National Archives, Kew, WO 416/251/231

[vi] National Archives, Kew > Blog > Opening up our prisoner of war collection last accessed 7 Sep 2024

[vii] Image © National Archives WO 416/251/231

[viii] Ancestry.co.uk UK World War II Casualty Lists > Other Ranks (10 Sep 1940-01 Oct 1940) last accessed 7 Sep 2024

[ix] Bombsight.org Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941, Ref: 56 18 NW last accessed 7 Sep 2024