Edwin George Albert Mayhew was born in Fulham, London, on 8 May 1919, the only child of Charles Edwin Mayhew and his wife Elizabeth (nee Jolly). Although both father and son were known as ‘Ted’ throughout their lives, for the sake of clarity, this story is about the younger Ted.

Little is known of Ted’s early life, however after serving an apprenticeship he was employed by London Transport as an Electrical Engineer[i] where he may have worked on the London Underground, the new-fangled trolleybus system, or in another area altogether.

Ted’s life changed forever after the Military Training Act 1939 was passed as a response to Hitler’s threat of aggression in Europe[1]. The Act required all British men aged 20 and 21, including Ted, to undertake six months’ military training with a view to being quickly deployed into active combat roles if required. On 3 June 1939, the first – and only – cohort of liable males were registered and underwent a medical examination and call-up for Ted and his peers deemed fit and able soon followed[ii].

[1] This Act was superseded on the outbreak of war in September 1939 by the National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939 which would enforce conscription on all male British subjects between 18 and 41, except for a few exemptions.

Ted was released by his employers and was assigned to the 367 Battery of the 140th Army Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, on 20 October 1939[iii]. Formed in May that year, this was a Territorial Army Unit of about 700 men plus support staff based in South London with a Regimental Headquarters (RHQ) in Clapham, 366 (10th London) Battery based in Lambeth and 367 (11th London) Battery, based in Woolwich.

At the time, British field artillery tactics were organised to provide groups of gun strong points, usually hidden by trees, as close support for infantry and armour, with a communications track to the rear to bring in supplies and ammunition, plus forward observation posts connected by telegraph wires. Each field regiment was organised as an RHQ and two batteries, each with twelve guns. These were 18-pounders based on a WW1 pattern towed behind tractor units, with an ammunition limber positioned between the tractor and the gun[iv].

Both batteries were sub-divided into three troops, each with four guns and shared radio communications. Each gun was crewed by six men: a sergeant in overall charge, a No. 3 as his right-hand man, a lance bombardier who laid and fired the gun, Nos. 2 and 4 who loaded and rammed the shells, and Nos. 5 and 6 who fetched and carried the ammunition. Ted was likely to have been trained as a No. 2, 4, 5 or 6.

In November 1939, two months after the 140th Field Regiment mobilised under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Cedric Odling, a seasoned WW1 veteran, when the men had been equipped and had finished basic training in London and Dursley, Gloucestershire. The regiment was assigned to join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and, on 2 March 1940, left Dursley for Southampton, then travelled by ship to Le Havre, in France, landing on 6 March 1940[vi].

The convoy was nearly six miles long and comprised of nearly two hundred camouflaged vehicles: 3-ton lorries, 30-cwt lorries, 8 and 15-cwt trucks, gun tractors, armoured carriers, ammunition, machine guns and other equipment bearing the 140th Field Regiment identification logo (the number ’10’ on a red and blue background)[vii].

Ted, who was just 20 years old, and his fellow soldiers, mostly in their late teens or early twenties, were not yet considered adults as they were still too young to vote. Despite their youth, they must have felt a dizzying mix of excitement and trepidation as they watched the shores of England fade into the distance for the first time. Most of these young men had been born after the First World War, a terrible conflict which became known the ‘War to End All Wars’, in which most of their fathers had probably served. Ted’s own father had enlisted during the first couple of weeks and may have tried to forewarn his son about what might lie ahead fighting a war in mainland Europe. However, young lads – then as now – are not typically known for heeding parental advice.

Once in France, Ted’s regiment initially travelled by train to Bolbec, where the junior ranks were billeted. From there, they travelled by road eastwards across northern France to the town of Auchy, where they took over billets from the 97th Field Regiment for three weeks[viii].

The regiment experienced their first casualty on 19 March 1940 when Lieutenant Harrison was involved in a motorcycle accident and was taken to hospital in Dieppe[ix], then a terrible event occurred on 10 April 1940 when 23-year-old Gunner J Lee of 366 Field Battery was found dead. He had been asphyxiated by carbon monoxide fumes, but the War Diary does not speculate on whether this was accidental, or otherwise[x]. Gunner Lee’s funeral service was held at the Roman Catholic church in Auchy, attended by officers of his unit, and his body buried with full military honours in Douai Communal Cemetery Military Section[xi].

In the weeks preceding the anticipated German invasion of Belgium, the regiment underwent extensive training, and firing exercises in the flat landscape of Northern France, where Ted’s father had endured his own time on the Western Front less than twenty-five years earlier. Indeed, many of the regiment’s senior officers had then been junior officers, and names of many towns and villages would have evoked memories of the horrors of the war of attrition, marked by prolonged fighting and heavy casualties – on both sides – where both sides sought to exhaust the other’s resources and manpower without achieving any decisive victories.

Since those terrible days, aircraft and tank technologies had greatly improved, along with communications technologies. German military leaders had invested all their efforts and relatively limited military resources and manpower into a tactic known as ‘Blitzkrieg’ – a German word meaning ‘lightning war’. This was a rapid and overwhelming concentration of force using a combination of tanks with mobile infantry and artillery troops, reinforced with close air support. The drug Pervitin, a type of amphetamine, was widely distributed by the German military to increase alertness, reduce the need for sleep, and boost the overall stamina and endurance of their soldiers.

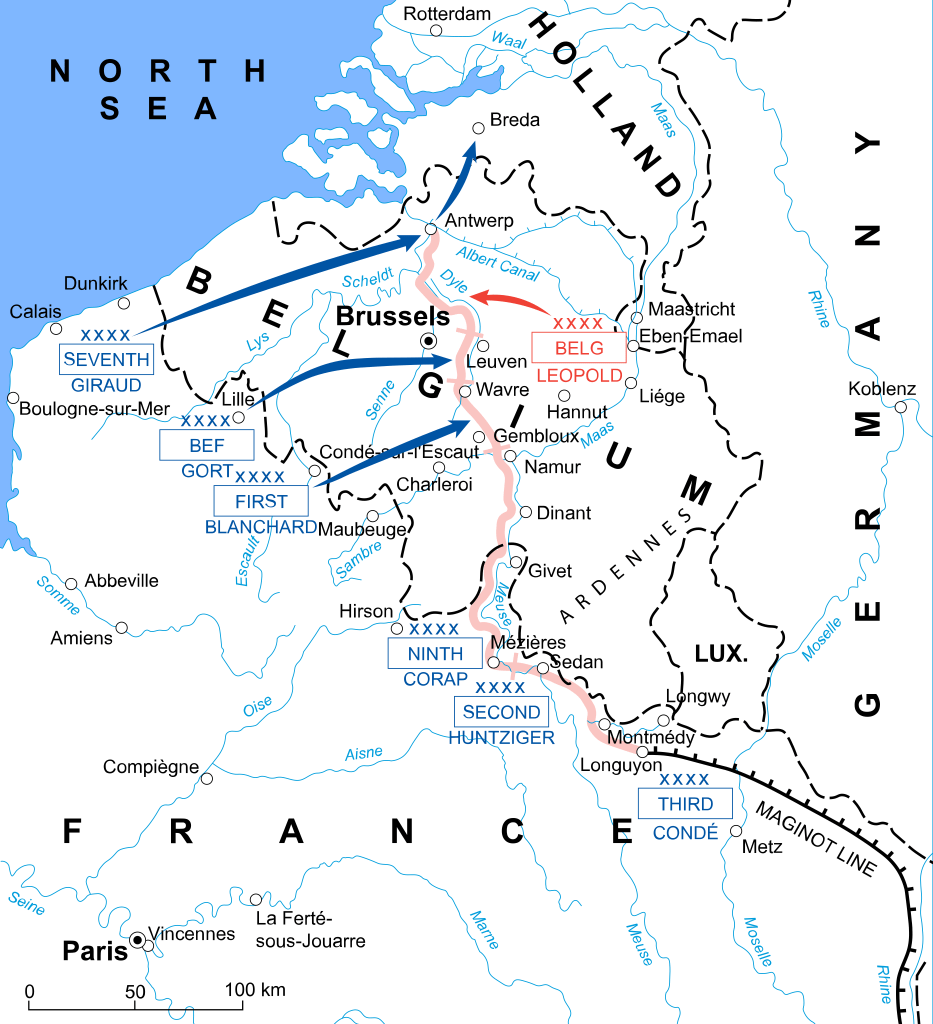

As anticipated, on 10 May 1940, German armies invaded Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and France. The 140th Field was in training at Toutencourt in France when they heard on the wireless at 7am that Belgium and Holland were being invaded, so plans for the day were immediately cancelled and they packed up ready to move[xii].

At 2:30pm the regiment headed off, and marched through Arras and Douai to Faumont, arriving about seven hours later to join the BEF’s defence of the line at the river Dyle. They crossed the border into Belgium soon after midnight and passed through Brussels before dawn[xiii].

During the night of 13-14 May, the 140th reached their position between Huldenburgh and Overyssche where they made their first contact with the enemy that same evening. At 7pm the following evening, they opened a heavy bombardment on enemy infantry concentrated on the east side of the river Dyle[xv]. Allegedly this was the first British artillery round fired during the Dyle-line defence[xvi].

However, the huge German armoured columns had by now effected the second part of their plan and smashed through the lightly defended Ardennes to the east and were advancing north towards the English Channel. The BEF were forced to withdraw to the line of the Escaut river[xvii] and, on 16 May, the 140th Regiment was ordered to withdraw to defend the west of Brussels[xviii].

As the British troops approached Brussels, they encountered roads filled with thousands of civilian refugees, laden with whatever belongings they could carry, travelling by car, horse and cart, bicycle, and on foot, fleeing German air attacks on their homes and heading towards the perceived safety of France. Shockingly, part of the German strategy had been to generate refugee problems and effectively create human roadblocks to stall the progress of the BEF. Civilians were encouraged by enemy agents disguised as soldiers or civilian officials to leave as quickly as possible by spreading panic among them, then aircraft were sent in to fly low over the retreating convoy and occasionally opening fire.

The sight of these terrified families – women, children, and the elderly – desperately trying to flee the chaos of war must have been shocking to Ted and his comrades. They likely experienced mixed emotions, ranging from compassion for the refugees to frustration and anger at the injustices being inflicted upon these innocent people who, until recently, had simply been trying to peaceful lives within the sanctity of their homes.

Some of the young soldiers of the BEF might even have felt an emotional connection to the experiences of their father’s generation, who had served during the First World War. Perhaps they were now becoming aware of the struggles and sacrifices endured by previous generations as they now found themselves caught up in a comparable situation defending Northern Europe, and ultimately their homeland, from the advancing enemy troops.

Although the next couple of days passed without major incident, tensions were mounting as the German advance quickly pushed forwards and threatened to overwhelm the right flank of the BEF’s defensive position. The 140th was ordered to withdraw about 60 miles south-west towards the strategic position of Tournai on the Escaut river, one of the oldest cities in Belgium not far from Mons, the site of the first battle between the British and German forces in 1914.

This historic city had been coming under intense German bombardment for several days and nights and, by the time the 140th passed through during the night of 18-19 May, almost all the buildings in the centre of Tournai had been destroyed by the bombs and was now in flames with many bridges blown and three lines of traffic on the main road[xx].

In the morning, the regiment reached their position on a ridge behind the Escaut river between and two battery positions were set up between the villages of Ere and St Maur, with the HQ in a farmhouse in Ere. Here, the batteries came under heavy shelling which resulted in the regiment’s first combat death when Lance Bombardier Thomas Bennett of 366 Battery was killed. Several other men were wounded, and three of their twelve guns were put out of action[xxii].

By 22 May it was becoming clear that the BEF was being outflanked so the 140th withdrew further, crossing the border back into France before setting up the two batteries about a mile apart. 367 Battery was only in position for about 24hrs and was not involved in any combat firing, but 366 Battery, with only nine guns after the shelling at Ere, was instructed to separate from the regiment and come under the temporary command of 27th Field Regiment of the Royal Artillery[xxiii].

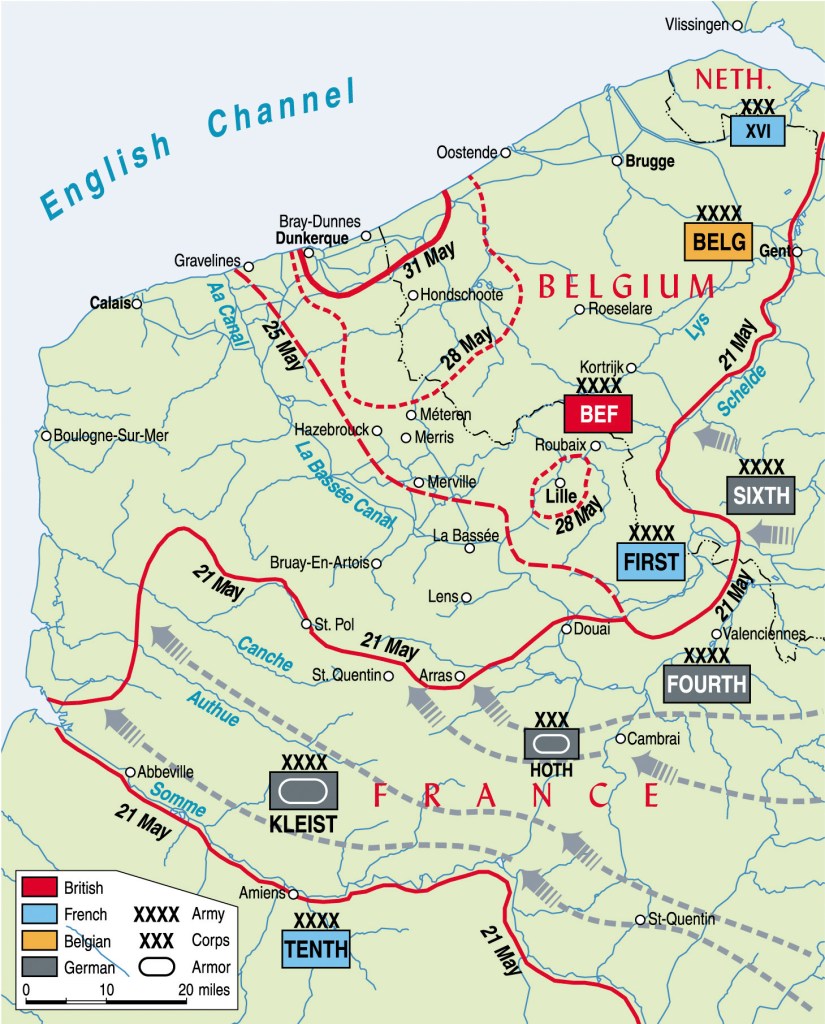

The next day the two batteries went their separate ways, with orders for 367 Battery and the regiment’s HQ staff commanded by Lt Col Odling, to head about 30 miles west towards the Nieppe forest. They were to join the ‘Macforce’, a hastily formed force commanded by Major General Noel-MacFarlane, and one of several attempts to stem the German advance by acting as a rear guard to try and facilitate the escape of the British troops.

At this time, the British and French line of defence was positioned along a series of canals running north-south from Gravelines on the coast to La Bassee, 40 miles to the south. Behind this line lay several defended strong points, including Hazebrouck, Cassel, and Wormhoudt. Hazebrouck was known to be the German objective, and the Nieppe forest lay just to the south of the town. The forest was guarded by three battalions of the Royal West Kent Regiment and a battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment[xxv].

On Thursday May 23, Ted and the men of 367 Battery with eleven guns were ordered to join Macforce. They marched through Lille and Armentiers and arrived at the Forêt de Nieppe at 11pm. Next morning, 367 Battery was ordered to rendezvous in a small wood, but this was found to be a hopeless place, so they didn’t stay and instead returned to the Forêt de Nieppe. They were then ordered to join an advance guard and march through Caestre to the north-east of Hazebrouck towards the strategic hilltop town of Cassel, which they were to defend from the enemy[xxvi].

Somehow the French army had managed to stall the German advance temporarily, so Macforce was disbanded. The 140th Field Regiment was then grouped with the 5th Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery[xxvii]. Both regiments now formed part of 145 Brigade, under the command of Brigadier Nigel Somerset, great grandson of Lord Raglan who had been the British Army’s Commander-in-Chief at the time of another desperate action: the Charge of the Light Brigade during the Crimean War[xxviii]. The brigade group, known as ‘Somerforce’, included 145th Infantry Brigade (2nd Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment, 4th Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry), backed up with armoured cars of the East Riding Yeomanry, and various support units, including the 140th Field Regiment and 5th Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery). Somerforce’s role was to hold the line from Cassel to Hazebrouck, at the outer perimeter of the Dunkirk pocket and had set up a number of strongpoints along the railway lines manned by small units of soldiers.

Earlier that morning at 7am, orders had been received that Somerforce was to proceed to Calais to defend it at all costs against the German advance. However, by 3pm, a new order arrived that Somerforce was to proceed to Cassel instead. On the way to Cassel, a radio message instructed Somerset to send three of his five battalions to Hazebrouck instead. This left just two battalions, the 2nd Glosters and 4th Ox and Bucks, plus some tank and artillery support including the men and equipment of 367 Battery, to protect the town of Cassel.[xxix]

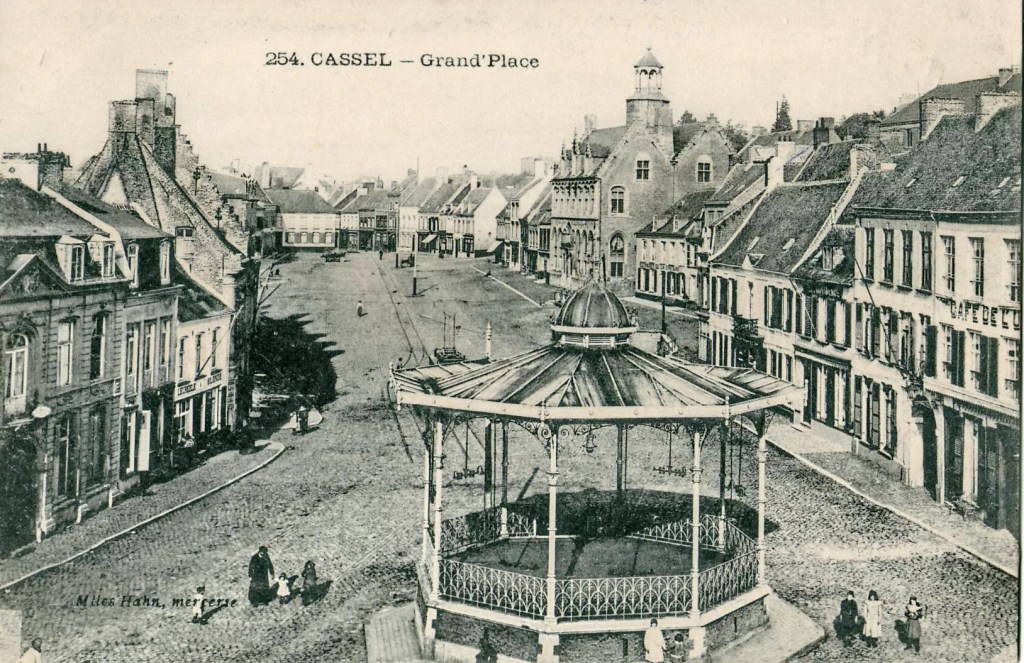

The troops headed north and arrived around midday on Saturday 25 May, just as Cassel was being heavily bombed. The Chaplain of 145 Brigade describes what he saw as they drove into town: ‘The road into Cassell is very picturesque; it rises out of the flat plain, through a series of well-wooded foothills, until suddenly the mass of the hill on which the town stands rises up ahead. The last long climb follows a series of zigzags up the steep face of the hill, until the road takes a sharp right-angle bend straight into the narrow main street.’[xxx]

367 Battery, including Ted, would have been one first units to arrive on the scene and witness the destruction and horror of the many civilians, including French and Belgian refugees, and a whole column of French Army transports and supplies that had been bombed and machine gunned from the air. No humans or animals appeared to be left alive in the town as those that remained had taken shelter underground in cellars[xxxii].

Nevertheless, the three troops of the battery went into action under the 5th RHA, and the regimental HQ was set up in a nearby chateau. Cassel’s elevated terrain in a relatively flat environment provided a strategic advantage allowing the defenders to observe and target any approaching German forces and there was just enough time to site several strong points along a key road north to Dunkirk. Brigadier Somerset began to allocate the positions to be held by the two infantry battalions, with the 2nd Glosters to hold western section and the 4th Ox and Bucks the east, with artillery support from units including 367 Battery.

However, a lot of work was quickly needed to make Cassel defendable. Under the supervision of men from the Royal Engineers, roadblocks were put in place on all the main roads leading into the town. These roadblocks were to be covered by the artillery guns and the brigade’s nine anti-tank guns. Walls of buildings around the edge of town had small holes knocked out of them to allow the defenders to observe or fire weapons at any attackers, much like the arrow holes in a castle wall, and the roofs and ceilings were shored up to effectively convert the town into a fortress.

Despite the advancing German Army having already been seen to the west of Cassel and fired upon by an anti-tank gun, on Sunday, 27 May at 7am all the senior officers involved in setting up the perimeter defences of Dunkirk converged upon Cassel for a meeting. It may be that Cassel was chosen as the venue as it been used by the French General Foch as his headquarters during the First World War and a statue erected in his honour gave the town a certain gravitas.

The plan to defend Dunkirk was quickly agreed upon, with the British responsible for the eastern sector and the French the west. However, a French general present at the meeting, General Fagalde, was furious that a section of the main Dunkirk to Lille road, which he had taken to reach Cassel, was already blocked by large English lorries abandoned by their drivers. He had complained to a British officer who told him that all personnel were being told to leave their vehicles wherever they could, and to evacuate from Dunkirk[xxxiii]. He had been unaware of the British plan to leave whilst the French were still ready to defend, or even go on the offensive. The meeting ended abruptly when the German artillery began to shell Cassel, leaving the dignitaries to escape back to their respective headquarters.

Shortly afterwards, some twenty Panzer division tanks and a hundred German infantrymen on foot were spotted heading towards Cassel. Meanwhile, a battalion of men from the Sherwood Foresters which had taken a wrong turn on their way to Dunkirk, were passing through Cassel when they were dive-bombed from the air resulting in heavy casualties.

At the same time, the regimental HQ based in the Chateau Masson suddenly found itself on the front line, so one 18-pounder gun was set up at a crossroads as an anti-tank defence supported by six anti-tank rifles and Lewis guns and helped knock out five tanks. However, the enemy managed to get into the Officers’ Mess in HQ and take their radio[xxxiv].

As the day progressed, despite the spirited resistance of the Glosters and the Ox and Bucks, two outposts on the approach to the town were overrun, and the enemy turned their attention to Cassel. The British units in Cassel worked in close coordination to maintain their defensive lines. although the communication and supply lines were disrupted due to the constant German pressure and bombardment. The defenders, despite being heavily outnumbered and outgunned, managed to hold their positions, inflicting considerable losses on the German attackers. The artillery fire from 367 Battery troops positioned in the town and in nearby woods was vital in repelling German assaults by targeting tanks, infantry, and artillery positions.

That afternoon, the troop from 367 Battery on the northern side of the woods found they were unable to elevate their guns sufficiently to fire over the top of Cassel towards the oncoming attackers. By 9pm, the regimental HQ and two troops south of the woods withdrew to Cassel as the infantry could no longer offer any protection for the guns, and anti-tank guns were taken up for all round defence. Other survivors of various regiments stationed at strong points along the main road were also forced to evacuate – if they were able – to Cassel, whilst the regiment’s depot and transport hub had also been badly disrupted by enemy action[xxxv].

At around midnight of 27-28 May, Commanding Officer Lt Col Odling was wounded, so his second in command, Major Christopherson took over[xxxvi], reporting to Brigadier Somerset at HQ.

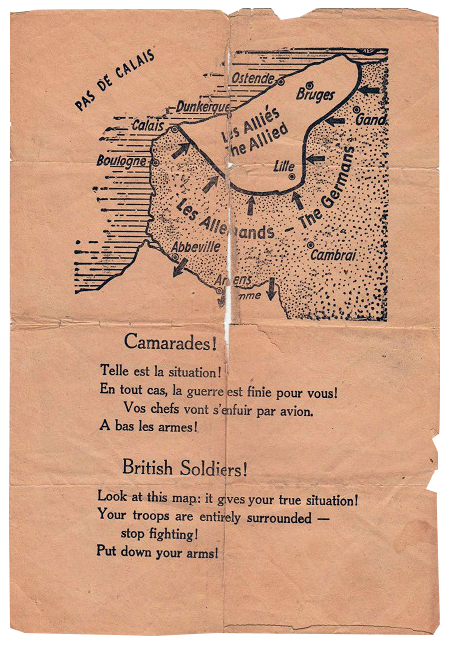

Even though Tuesday 28 May would later become one of the most significant days of the Second World War, marked by the Belgian surrender, the rapid withdrawal of the BEF towards Dunkirk, and the future of France – and Western civilization – hanging in the balance, the day was relatively quiet at Cassel. While the town was shelled all day, and enemy troops had been sighted digging in mortars to the northwest, which kept the northernmost troops busy firing continuously at them, there was no major attack and little enemy movement seen during daylight[xxxvii]. That evening, in the pouring rain, the German Luftwaffe dropped thousands of leaflets into the town urging the troops to surrender.

Without doubt, the situation within Cassel was becoming untenable. Food and ammunition were running low, the men were exhausted, and they hadn’t eaten a proper meal for a week, existing on ration packs, biscuits, and chocolate. The lack of fresh water, claustrophobically hot weather[xxxix], and poor sanitation only compounded the dreadful situation as the enemy closed in.

The following morning, the barrage of shells upon the town began at first light, and their accuracy was improving, causing the numbers of dead and wounded within the town to mount. Major Christopherson was wounded and two of his detachment killed when their 18-pounder was targeted as they fired on enemy mortars on the plains below[xl]. Brigadier Somerset, as Brigade Commander, was aware that the BEF was embarking at Dunkirk to return to Britain, and he fully expected and awaited a ‘vigorous counter-attack by British and possibly French Troops to try to restore the situation’[xli].

Cassel was by now in ruins from air bombing and, in his diary, Lieutenant Tom Carmichael, an East Riding Yeomanry officer, whose tanks and carriers had been ordered to hold the road winding up on the eastern side of Cassel described the scene as they entered the town: ‘… the enemy guns were ranged accurately on the road. The trees were shattered, two 2-pounders showed signs of direct hits, and a little heap huddled under a groundsheet marked the remains of one of the crew. But that was not the worst. On turning into the town, a 3-tonner…carrying personnel had suffered a direct hit…’ he then described the terrible scene of the dead who remained where they had fallen, a sight ‘made more terrible by the cold and rain’[xlii].

However, at 10am on 29 May a dispatch rider arrived with written orders for the Brigade Commander to withdraw to Dunkirk and attempt to join the evacuation, known as Operation Dynamo. Unfortunately, the messenger had failed to get through to Cassel the previous night, and – inexplicably – this withdrawal order hadn’t been sent via radio communication, despite contact being maintained for the previous 48hrs. Brigadier Somerset confirmed back to Divisional HQ that he intended to withdraw that night after dark, and the response was a further order to abandon all transport and heavy weapons before attempting to break out across country towards Hondeschoote, and on to the Belgian border to the northeast[xliii].

As the day wore on, enemy action became more intense with mortar bombardments and infantry attacks causing significant casualties to both officers and men in nearby strongholds and Cassel itself[xliv]. Then, at 4pm, orders for the move were issued to the various regiments. Nonetheless, all wounded, including Lt Col Odling, were to be left behind with food and water, and volunteers from the Medical Orderlies[xlv].

By 5pm the 18-pounders were running short of ammunition, and orders were issued to disable any equipment being left behind to avoid working weapons falling into enemy hands. Gun sights were destroyed, and firing pins removed. Motor vehicles were sabotaged with tyres slashed, petrol tanks pierced, and radiators smashed. It must have been a truly crushing experience to prepare to give up the town they had held so valiantly[xlvi].

It was a very warm, dark night when, at 10:30 pm, the evacuation began. Led by the 4th Ox & Bucks, the column included Brigade HQ Staff, Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers, and others, including Ted his comrades from the 140th Field Regiment, with the Glosters and East Riding Yeomanry bringing up the rear. They filed out of the garrison silently on foot, carrying only small arms, and made their way across the country towards Watou, with a planned rendezvous at Hondeschoote on the outskirts of Dunkirk.

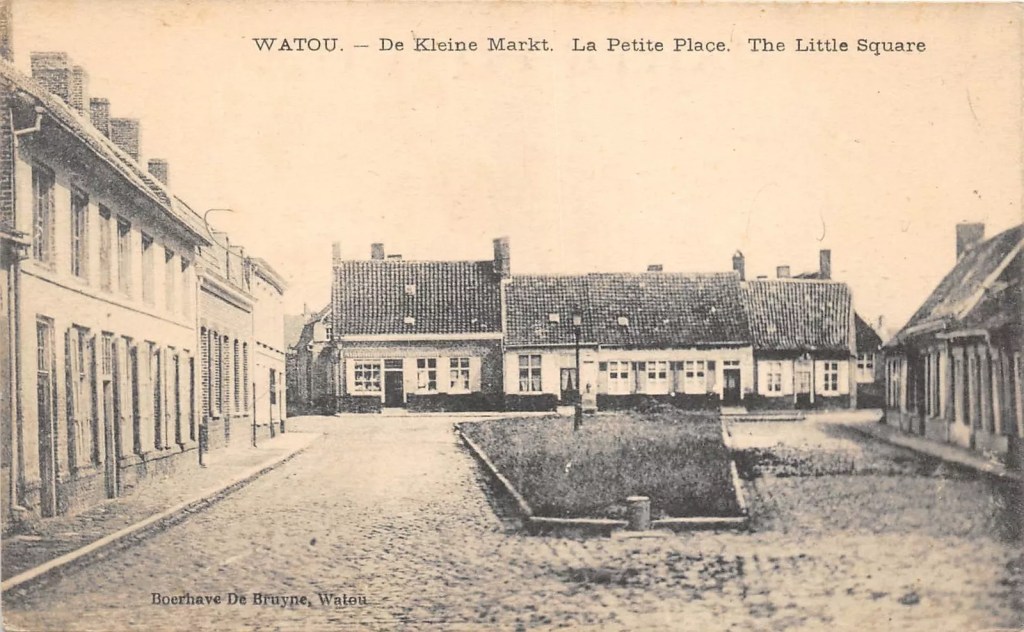

This breakout should have taken place 24 hours earlier, but the delay in the orders reaching the Brigade Commander meant that the enemy had effectively severed all routes to the sea[xlvii]. Unbeknownst to them, Watou, which they believed to be in British hands, had been taken on 28 May when King Leopold III, Commander-in-Chief of the Belgian Armed Forces, signed the unconditional surrender of the Belgian Army.

As they left Cassel, the men were likely aware that the situation was almost hopeless, and that this breakout was their only chance of survival. They would not have known about the terrible violence and atrocities being committed by German forces in the surrounding countryside against both Allied combatants and civilians. Units such as the Waffen-SS, known for their brutality and adherence to Nazi ideology, were often involved in such war crimes, and their presence in the region contributed significantly to the atrocities committed in the area.

Once the British forces withdrew, the German forces quickly moved in to occupy Cassel and the surrounding strongpoints.

As the officers and men attempted to make their way across the countryside via woodlands and ditches around open fields, the invading forces shone searchlights across the flat landscape and set barns and villages ablaze to try and light up the area.

When the men silently marching in line approached Winnezeele they were fired upon by German guns, and the units which had intended to march in line, split into several groups to try and escape. The leading party confronted the enemy at Winnezeele, where Major Graham of the 4th Ox & Bucks was killed leading a bayonet charge trying to clear the way. Eventually, the group reached Watou, only to face the enemy again. Tragically, after having come so far, many of the party were killed or mortally wounded. Most of the survivors were then captured, including the Brigade Commander Brigadier Somerset.[l].

About halfway between Winnezeele and Watou, the 2nd Glosters had diverted off course but managed to reach a ditch along the Franco-Belgian border. They successfully concealed themselves for most of the day in woodland. When they were eventually discovered, they attempted to escape but were forced to surrender after sustaining several casualties[li].

One group managed to pass undetected to the north of Watou and was well on the way to Hondschoote before they were spotted by the enemy. They too surrendered after putting up a stiff fight in a minefield.

The rear party, finding Watou occupied by enemy tanks, attempted to make a detour to the south of the village but soon found itself surrounded by a strong enemy force consisting of tanks, guns, mortars, and motorised infantry in armoured troop carriers. Any attempt at resistance would have been suicide, so they too surrendered.

The exact circumstances of Ted’s capture remain unknown, but he, along with other prisoners, was marched at gunpoint into Watou. Horrifically, several officers and men were shot as they attempted to surrender, while others who were too wounded or exhausted to march were also executed in cold blood. At just 21 years old and less than three months in France, Ted faced the grim reality of spending the remainder of the conflict as a Prisoner of War…

Of the 321 men of 367 Battery, 140th Royal Field Artillery, it is believed only three made it to Dunkirk to be evacuated back to Britain. Of the rest 102 were killed or wounded, and 216, including Ted – were captured[liii].

For Ted and his fellow prisoners, their journey was far from over. The hardships and brutalities they would endure in captivity would be a stark continuation of their suffering, a relentless struggle for survival under increasingly dire conditions…

Click here to read the next chapter…

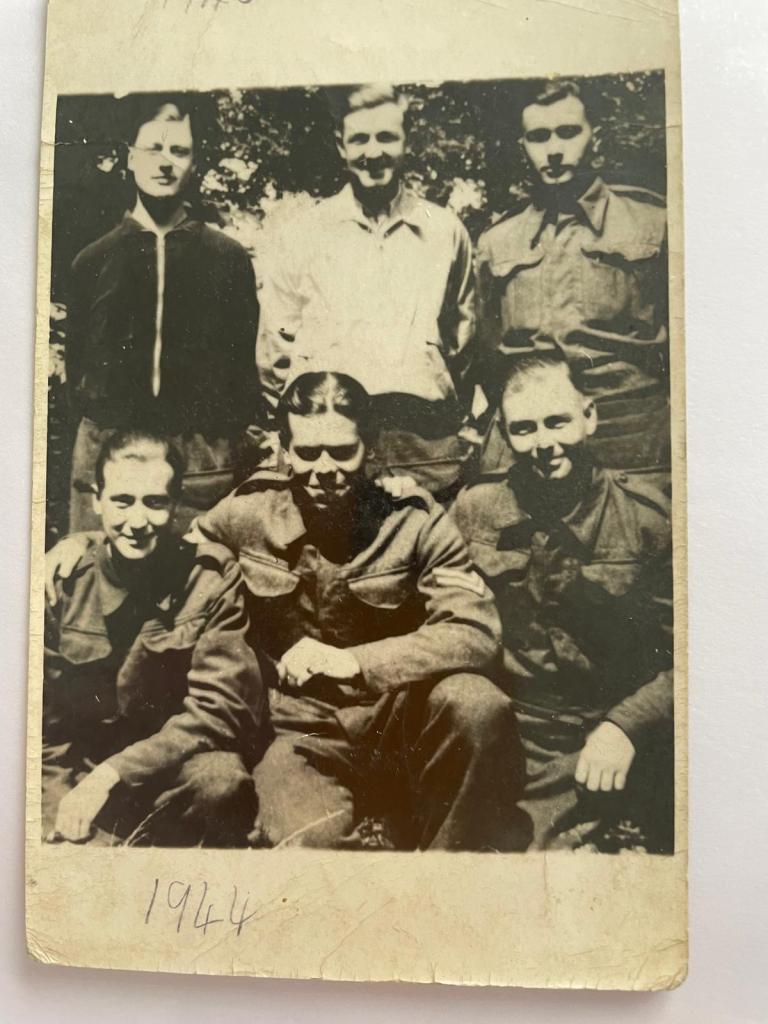

With grateful thanks to John West and his excellent website 140th (5th London) Army Field Regiment, Royal Artillery which tells the Regiment’s comprehensive story between 10th and 31st May 1940. His father Eric West and Ted Mayhew appear together in several prisoner of war photographs, and may have served together in ‘F’ Troop of the 367 Battery.

[i] 1939 Register England & Wales, London, Fulham Met B, Reference: Rg 101/140f, National Archives via https://ancestry.co.uk

[ii]Military Training Act 1939 via https://en.wikipedia.org last accessed 28 Apr 2024

[iii] Gnr EGA Mayhew 945507 Liberation Questionnaire, National Archives

[iv] 140th (5th London) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery via https://en.wikipedia.org last accessed 28 Apr 2024

[v] Image via https://commons.wikimedia.org last accessed 28 Apr 2024

[vi] 140th Field Regt War Diary WO 167/507 via National Archives

[vii] http://140th-field-regiment-ra-1940.co.uk last accessed 29 Apr 2024

[viii] 140th Field Regt War Diary WO 167/507 via National Archives

[ix] Ibid

[x] Ibid

[xi] Ibid

[xii] Interview with Major N Christopherson 2nd in Command of 140th Regiment 20 Jun 1945, National Archives

[xiii] Ibid

[xiv] German invasion of Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France in May 1940. The planned positions of the Allied Armies. Public Domain, via https://commons.wikimedia.org last accessed 29 Apr 2024

[xv] Interview with Major N Christopherson 2nd in Command of 140th Regiment 20 Jun 1945, National Archives

[xvi] 140th (5th London) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery via https://en.wikipedia.org last accessed 28 Apr 2024

[xvii] Ibid

[xviii] Interview with Major N Christopherson 2nd in Command of 140th Regiment 20 Jun 1945, National Archives

[xix] Bren gun carriers pass Belgian refugees on the Brussels-Louvain road, 12 May 1940, Public Domain, via https://commons.wikimedia.org last accessed 29 Apr 2024

[xx] Interview with Major N Christopherson 2nd in Command of 140th Regiment 20 Jun 1945, National Archives

[xxi] http://visitevirtuelletournai.over-blog.com last accessed 29 Apr 2024

[xxii] http://140th-field-regiment-ra-1940.co.uk last accessed 29 Apr 2024

[xxiii] Ibid

[xxiv] Map of the rapid German onslaught across France in May 1940 via https://warfarehistorynetwork.com last accessed 29 Apr 2024

[xxv] http://140th-field-regiment-ra-1940.co.uk last accessed 29 Apr 2024

[xxvi] Interview with Major N Christopherson 2nd in Command of 140th Regiment 20 Jun 1945, National Archives

[xxvii] Ibid

[xxviii] Dunkirk, Fight to the Last Man, by Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, published Penguin 2006

[xxix] Ibid

[xxx] Ibid

[xxxi] Image in the public domain via www.westhoekpedia.org last accessed 28 May 2024

[xxxii] Dunkirk, Fight to the Last Man, by Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, published Penguin 2006

[xxxiii] Ibid

[xxxiv] Interview with Major N Christopherson 2nd in Command of 140th Regiment 20 Jun 1945, National Archives

[xxxv] Ibid

[xxxvi] Ibid

[xxxvii] Ibid

[xxxviii] German propaganda leaflet via https://dunkirk1940.org/ last accessed 28 May 2024

[xxxix] https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories last accessed 28 May 2024

[xl] Interview with Major N Christopherson 2nd in Command of 140th Regiment 20 Jun 1945, National Archives

[xli] Letter from Brigadier Somerset to the Editor of the Daily Telegraph 19 Feb 1948

[xlii] Dunkirk, Fight to the Last Man, by Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, published Penguin 2006

[xliii] War Diary of the 145 Infantry Brigade – 4th Battalion, The Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and 2nd Battalion, The Gloucestershire Regiment via https:// https://www.prisonersofwarmuseum.com/ last accessed 28 May 2024

[xliv] Ibid

[xlv] Ibid

[xlvi] Ibid

[xlvii] Ibid

[xlviii] Image believed to be in the public domain via https://www.materielsterrestres39-45.fr/ last accessed 28 May 2024

[xlix] [xlix] Image believed to be in the public domain via https://www.materielsterrestres39-45.fr/ last accessed 28 May 2024

[l] War Diary of the 145 Infantry Brigade – 4th Battalion, The Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and 2nd Battalion, The Gloucestershire Regiment via https:// https://www.prisonersofwarmuseum.com/ last accessed 28 May 2024

[li] Ibid

[lii] Map created via https://www.openstreetmap.org

[liii] http://140th-field-regiment-ra-1940.co.uk last accessed 29 Mar 2024